Created Using 715,000 Photos, the Most Detailed 3D Model of the Titanic Challenges Beliefs

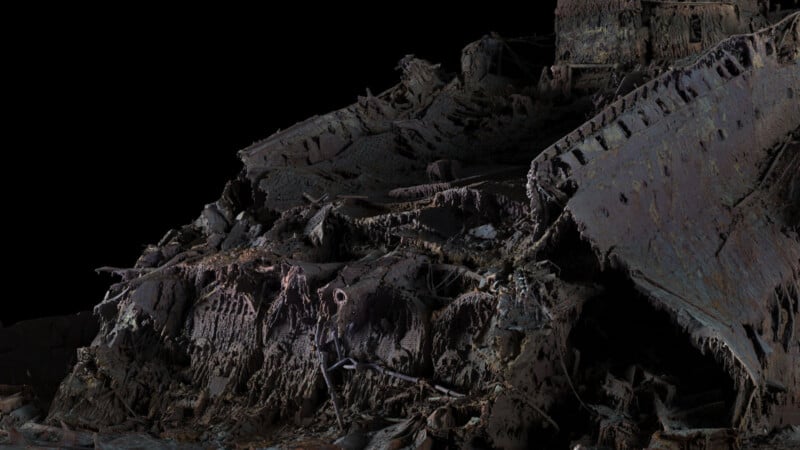

A new National Geographic documentary, Titanic: The Digital Resurrection, takes a deep dive into the infamous Titanic disaster and centers around a cutting-edge 3D model of the shipwreck, created using 715,000 digital images captured 12,500 feet below the surface of the frigid North Atlantic Ocean off the coast of Newfoundland.

PetaPixel spoke with William McMaster, the 3D Lead and Technical Director for the new documentary and co-founder of Megascapes, a 3D model creation company. McMaster is a pioneer in immersive media, with over a decade of experience capturing and producing 360-degree immersive video, visualizations for VR, and detailed photogrammetry and modeling projects, like the one he embarked on for National Geographic in 2022, at the time for Magellan, a deep-sea mapping company. That incredible work in 2022, which took weeks to capture and months to process, is now getting its major world premiere when Titanic: The Digital Resurrection premieres tomorrow, April 11, at 9 PM EDT.

“It’s been a number of years now since I actually completed the model — we captured it in 2022 and I was working on it in 2023 — so seeing it come together in this final program is just awesome,” McMaster tells PetaPixel.

McMaster and his team captured well over 700,000 photos of the Titanic in its final resting place in the North Atlantic, covering nearly every inch of the shipwreck from multiple angles. It was challenging to capture the images, requiring remotely operated vehicles and cameras that take four hours to get from the team’s boat to the Titanic itself. It was also highly time-consuming to go from the raw images to the finished model.

Since there was so much data, 16 terabytes’ worth, McMaster and his team could not create a single finished model in one fell swoop. They needed to craft the models piece by piece and then put those together.

“In total, I think it took about six months of work or so to assemble the final model,” McMaster says. “One of the most amazing moments in the entire project was when I was sitting there in my office next to my workstation and I kind of saw the final model come together finally and almost assembling it like a jigsaw puzzle. Seeing that final completed puzzle was a pretty amazing moment because I realized that I was actually the first person in the world to see what the whole wreck actually looks like. And I was just sitting there in my office just by myself finishing up the work I was doing on it. It was a pretty profound moment.”

McMaster then loaded the new model into Unreal Engine and looked at it through a VR headset.

“I just explored it in VR and it was crazy because when you see [the wreck] in its actual scale… it’s amazing.”

Beyond the time challenges of working on this project, getting consistently good, detailed photographs that far underwater is also quite tricky. However, it wasn’t the lack of light that was a problem — McMaster says they used extremely bright LED flash arrays on the remote vehicles. Instead, it was the particulate matter that the ROVs stirred up when working underwater.

“In terms of getting a bright exposure of the surface of the wreck, that was relatively easy because those flashes just blast an enormous amount of light for every exposure,” he says. “The other challenge though is dealing with particles and things floating around. As soon as the ROV gets a little bit close to the wreck, it stirs up particulate matter. If that happens, you either have to wait a few minutes or go somewhere else and mark the original position to come back to later.”

Given how detailed the new 3D model of the Titanic is — and it is exceptionally detailed — one might think that the camera McMaster and his team used must be high-resolution. But, no, it’s a 5-megapixel Micro Four Thirds-based camera system.

“It was sort of made for underwater — it’s good for low light,” McMaster says of the specialized camera.

“That’s kind of the key thing actually, is that that camera is very low noise and that sensor is very low noise. And because we had such a bright flash array, we were able to bounce a ton of light off of the surface and so able to use very low ISO very clean imagery,” McMaster continues.

“And so when you have really clean imagery like that, photogrammetry algorithms are able to pull out a lot of detail from things. So if you’re shooting photogrammetry with a phone or something like that, phone image sensors have a lot of noise in them and artifacts from digital processing and stuff. When you have really clean imagery, you don’t necessarily need 100-megapixel cameras to do a reconstruction of something that gives you a lot of detail. Because of the properties of the camera and how many images that we had and all the overlap, we’re able to do a lot with still images.

By capturing 2D images from many different angles, it is possible to get a lot of 3D data for the shipwreck. Alongside the 2D images, the team also used LiDAR cameras to get richer depth data to help fill in the gaps when needed.

While the technical achievements are fascinating, the results are incredible, McMaster notes that despite the excitement of breaking new scientific ground and creating the most detailed 3D model ever of the Titanic, the fact it is an underwater gravesite was not lost on him and the team.

“It really struck me when I saw the wreck that it is a grave site. Thousands of people died. And the wreck has little traces, little elements of the people that were on the ship when it sank,” he says. “So on the side of the ship there are all these portholes all over the place and a lot of the portholes were swung open. So you can imagine that when it was sinking, maybe people open the portholes and were shouting for help or something like that. That was really striking to me. You’d sort of be going along and see a random porthole that was just popped open and you sort of would know that somebody was in there, somebody opened that during the disaster. Things like that reminded you that this is a horrible tragedy.”

The work also has implications today, nearly 113 years after the Titanic sank. Thanks to McMaster and his team’s work, new discoveries about the Titanic have been made that change the narrative about what happened on the horrible night of April 15, 1912.

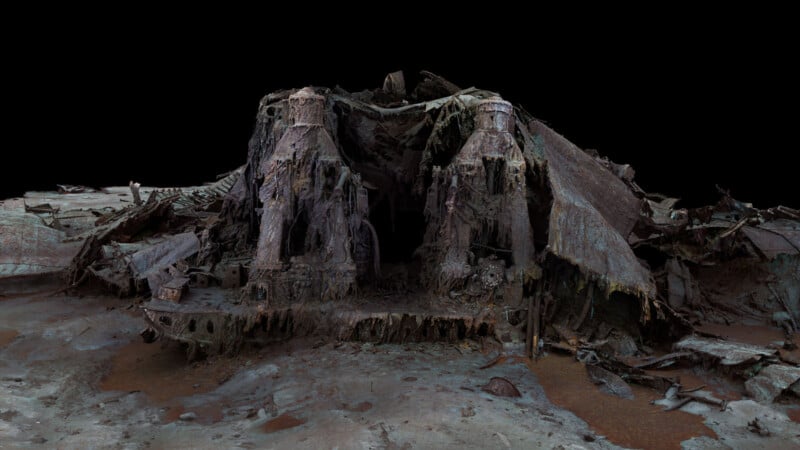

The team discovered a steam valve in the open position, which confirms eyewitness accounts that the ship’s engineers heroically remained at their posts in the boiler room for hours after impact, keeping the ship’s electricity running, which enabled wireless distress signals to be sent out. These 35 men, who sacrificed their lives, may have directly saved hundreds of others.

Further, detailed analysis of the digital scans provided fresh evidence that First Officer William McMaster Murdoch — quite a coincidental name, as it happens — likely did not abandon his post, as he has long been accused. Due to the position of a lifeboat davit, visible in the high-res scans of the Titanic, it seems that Murdoch was instead swept away into the ocean, where he perished, which aligns with the testimony at the time of Second Officer Charles Lightoller, who survived the sinking of the Titanic and died at age 78 in London in 1952.

![]()

Alongside the documentary premiering on April 11, National Geographic also published a corresponding story that digs deeper into the digital reconstruction and some of the novel discoveries that have been made.

Credits:‘Titanic: The Digital Resurrection’ is produced by Atlantic Productions for National Geographic. For Atlantic, Anthony Geffen produces, Lina Zilinskaite is the senior producer, and Fergus Colville is the director. Simon Raikes and Chad Cohen serve as executive producers for National Geographic.