How Four Award-Winning Women Change the World Through Photography

![]()

On March 8, International Women’s Day, Leica announced the four winners of its annual Leica Women Foto Project Award. Each woman’s award-winning project demonstrates the power of visual storytelling and exemplifies this year’s competition theme, unity through diversity. PetaPixel spoke to each winning photographer to learn more about their work.

Priya Suresh Kambli Connects Generations Through Multimedia Photography

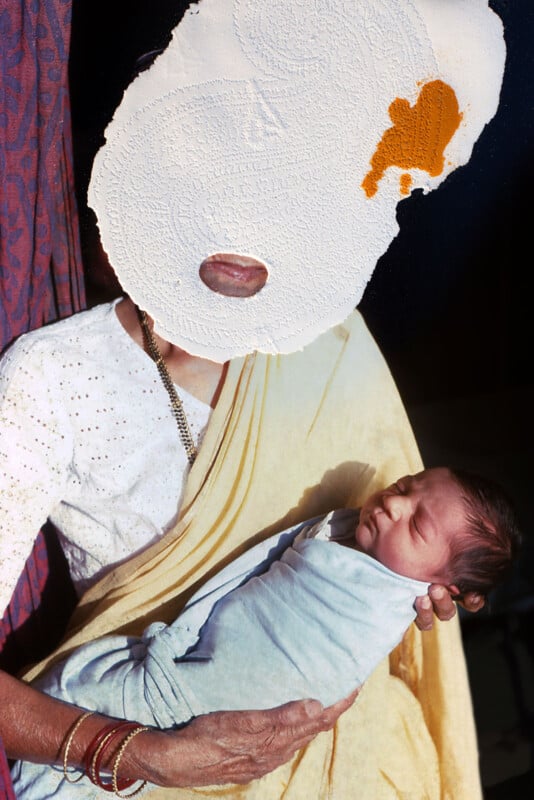

American photographer Priya Suresh Kambli was honored for her project, “Archive as Companion.” Kambli’s series, which combines traditional photography with multimedia artwork and handmade composites, investigates the migrant experience through a deeply personal lens.

“My approach to imaginatively exploring content is to combine labor-intensive practice with playful experimentation, which is an integral and intuitive part of my creative process,” Kambli tells PetaPixel. “Natural light, always a key ingredient in my work, becomes another material to manipulate — I use its mercurial nature as a sign of both the unpredictable and the transformational. I re-contextualize the familial qualities of the materials (flour, rice, pigments, spices, etc.) for my own artistic and creative purposes but also as a way of embellishing my past and connecting it to the present. It also plays games with them. With these materials, I alter the stories the archival photographs tell.”

“My work looks outward by documenting a story of migration and cultural hybridization that has particular resonance in a political climate marked by anti-immigrant rhetoric. It does so by mining an archive of family heirlooms, artworks, photographs, and other documents, even as it creates new images — new documents — which become part of that collection,” she continues.

Kambli has long been connected with photography. Her father was an avid amateur photographer and frequently photographed the family.

“My most vivid childhood memories are of standing beside my sister in front of my father’s Minolta camera — waiting while he carefully framed and exposed us onto film. My father took the task of making images rather seriously. And we (my father’s family) often found ourselves to be his unwilling subjects. Our reluctance was related to his perfectionism. We, his subjects, were constantly herded from one spot to another, posed in one pool of light and then another,” Kambli says.

“As a child, I was certain that being photographed by my father was my punishment.”

Now, Kambli finds herself behind the camera, occupying the photographer’s role that was once her father’s. However, she remarks that she now demands “the same commitment that I balked at. Hence most of my subject matter tends to be objects, artifacts, or self-portraits that I can put through the wringer without feeling that I am donning my father’s shoes.”

Kambli is a 25-year veteran of the photo field, having fallen in love with the craft during her undergraduate studies in design. She then pursued photography for her graduate studies and has been doing it professionally and as a teacher since. This year, Kambli will be a visual artist fellow at MacDowell, Peterborough, NH, and an artist in residence at the Headlands Center for Arts in California.

Kambli’s work relies heavily upon photography’s power to connect generations to each other.

“In my series Color Falls Down, I talk about my self-portrait as the constant that links my past with my present, that in this work I am neither Indian nor American, but the link that chains generations together,” Kambli explains.

And like she was for her father, Kambli’s children are part of her artistic journey, albeit with seemingly more excitement than Kambli herself once had.

“I always intended my work as my photographic inheritance to my children. Both my children have contributed to the work in multiple ways, by physically being part of it, my son’s question at age three; do you belong to two different worlds, since you speak two different languages? The essence of his question continues to be a driving force in my art making. And my daughter, who is my harshest critic and my most ardent supporter.”

However, the photographer adds that her family is not “specifically interested” in her work, which is “great” in a way, as it provides Kambli more artistic freedom.

Jennifer Osborne Turns the Lens Toward Courageous, Determined Heroes

Canadian photographer Jennifer Osborne uses her camera as a lens through which she can investigate current events. The photojournalist feels a deep responsibility to use her camera to help impact the world and incite necessary change.

“As land burns around the world, under record-breaking temperatures and with more intensity than ever before, this is a crucial time to be recognized for my work about conservation efforts. I would like to thank the committee for honoring my work at Fairy Creek with the 2025 Leica Women Foto Project Award,” Osborne tells PetaPixel.

Her award-winning series, Fairy Creek, focuses on a diverse group of activists who united in a cause to protect old-growth forests in British Columbia, Canada. The activists camped out for months, sometimes years, to protect the trees, some of which are more than 1,500 years old and among the longest-lived life forms in all of Canada.

“Because Fairy Creek hosts large old-growth trees, it plays a part in mitigating global warming. Ancient forests serve as carbon sinks. While human activities release carbon into the air, old-growth forests absorb some of it. But it only takes minutes to fell a 1,500-year-old-tree. If those same trees are designated for timber production and then cut, the stored carbon is released back into the air. My subjects at Fairy united to protect those trees. Every second they had to defend those forests, which host trees approaching 2,000 years of age, mattered. And Due to the actions of these devoted individuals, the B.C. government has extended a temporary legal order to protect the Fairy Creek watershed until September 2026,” Osborne explains.

She hopes that her award helps shed more light on the story of Fairy Creek and the courageous people who have fought to protect old-growth forests.

Unsurprisingly, Osborne plans to use her prize money and new Leica camera kit to document additional environmental issues, including disasters and extreme weather events. Osborne is no stranger to being in dangerous places, having previously done wildfire photography in Australia and beyond and conflict work in Ukraine.

Osborne, who is working on documenting wildfires in California, admits that it’s dangerous work that can seem strange to some people.

“It’s abnormal to run towards wildfires. Fire photography is taxing. One must keep a safe distance, while staying close enough to take meaningful pictures. Fire often requires long, grueling drives. Burned trees may fall and block my escape route. Traffic jams trap panicked people, causing them to escape fire on foot. At night, I sleep in my car because evacuees fill hotels, or power outages sometimes close everything,” the photographer explains.

A professional photographer since 2007, Osborne has occasionally needed to dig into her own pocket to fund some of her projects, including at Fairy Creek.

“During my time in Fairy Creek, I was rarely on assignment. I was out there at my own expense and on my own volition. I cared deeply about the story,” Osborne says.

“We, as photojournalists, are expected to remain neutral in the field. Yet we live in poverty as media budgets dwindle and staff jobs die away. Consequentially, there must be some kind of emotional connection to our subject matter that keeps us going. Indeed, there is more power in our work when the public feels we are ‘unbiased’ because our reporting can reach bigger audiences. And it’s not ideal when a journalist creates echo chambers with their work, by taking sides. Siding with a particular faction in more severe contexts, such as armed conflicts, is a personal security risk and, therefore, dangerous. Yet academics will argue that there’s no such thing as objectivity. Many write that objectivity is a ‘farce,’ or that it is ‘dead.'”

Osborne says documentary work is often “masochistic” and comes at a significant cost financially, emotionally, and personally.

“Like much of my professional life, I financed my work there and experienced a great loss of personal comfort,” the photographer admits.

In Fairy Creek and elsewhere, Osborne is fueled by the courage and determination of her subjects.

“Regardless of what happens to those trees in the decades to come, I hope my viewers will remember their efforts as meaningful and brave. They tried very hard to defend things much older than themselves,” Osborne says.

“I often focus my lens on disasters that impact the world. Over the past six years, I’ve concentrated on climate-related stories — particularly on wildfires. I previously photographed the resilience of people living through hardship, as well. Throughout all the stories I tell, the courage and trauma displayed by my subjects gives me energy to tackle difficult subject matter.”

Koral Carballo Investigates Identity Through Photography

Mexican photographer Koral Carballo’s project, Blood Summons, or La Sangre Llama in Spanish, deals with the complex concept of identity, specifically Afro-descendant Mexicans in Veracruz.

“My work is part of an effervescence that exists in Mexico to define what it is to be Mexican when we become aware of the colonial legacy that exists. For years, through the racist doctrine of José Vasconcelos on the La raza cósmica (cosmic race), a national project was appealed to [homogenize] the experience and erase the indigenous and Afro-descendant origin,” Carballo tells PetaPixel.

“My project La Sangre Llama is a counter-narrative of the national officialism on a given identity. It is a project that questions mestizaje and puts on the table that Afro-descendants were erased from many of the important chapters of history for the creation of the nation-state. Structural and state racism wanted to erase the experiences of my grandparents and made my parents’ generation assimilate this mestizo world.”

Through her photography, Carballo aims to bring to light hidden stories that reflect varied origins, struggles, and oppression within Mexico’s history. She also hopes to distance herself from a stereotypical Mexican tradition and identity she does not feel connected to.

Another aspect of Carballo’s award-winning project is to help people retake control over their identity and history.

“Reading this story and feeling these photographs are my bet to connect. Everyone has their own stories, and everyone knows whether or not to open their story, because doing this is painful and puts you in a vulnerable place. But this project is an invitation to not feel alone in our experiences but to understand that our stories are very important to create the new narratives we need to build hope in the present. To remember is to resist,” the photographer explains.

Carballo, who also does more traditional professional photojournalist and documentary work alongside her deeply personal projects, says every project is different. Projects like La Sangre Llama “are born from my guts, from very strong experiences that I lived.”

Sometimes, the driving force for her artwork is rage; other times, it’s hope or curiosity, maybe sadness.

“But these feelings are not defined and arise suddenly, they take over my body, my thoughts, my readings, the music I listen to, my ideas, and the energy to create,” Carballo says.

Her artistic process is long; sometimes, it takes years to bring a project to life. In the case of Blood Summons, the work has been incubating for Carballo’s entire life. She has been actively working on it off and on for over a decade, though, and time spent with family during the pandemic helped solidify specific ideas and create the right environment to bring the project to fruition.

“This project is [an attempt] to tell that there is not one Mexico but many Mexicos with diverse experiences through my personal history,” Carballo explains. “And to do it photographically is my language with which I want to transmit emotions, to put visually all these reflections that accompany me. These photos are the ones that are there in my mind and that are emerging through documentary-direct, metaphorical and [sensory] work. They have no order, they are images that are in memory but that together are a free story, where the viewer feels comfortable, inviting them to take the time to enter and reflect together.”

Anna Neubauer Provides Vital Visibility

Austrian-born, United Kingdom-based photographer Anna Neubauer’s winning photo series Ashes from Stone provides visibility to people who are far too often ignored or shunned by society, either because they don’t conform to societal norms or fit traditional beauty standards.

“Winning the Leica Women Foto Project Award is deeply meaningful to me as it is an incredible honor and validation of the stories I strive to tell. To me, photography is a way of seeing beyond the surface, of understanding resilience, identity and beauty in places where the world often fails to look,” Neubauer says.

“My work is deeply rooted in amplifying voices that are often overlooked, and this recognition not only fuels my passion but also gives these narratives a greater platform. It’s a reminder that storytelling has power to challenge perspectives, build empathy, and create change. Leica’s commitment to meaningful visual storytelling aligns perfectly with my own mission, and this award has allowed me to push my work even further. I really am truly grateful for the support and opportunity this award represents.”

A self-taught photographer, Neubauer got her first DSLR in 2010 and began taking self-portraits shortly thereafter. In the small Austrian town where she grew up, people didn’t believe artistic photography was “a real profession,” so she often worried about how other people perceived her passions and, as an extension, herself.

“However, photography quickly became my safe space, and sharing my work online connected me with a global community of creatives, which was incredibly special.”

In 2021, Neubauer went for it and became a full-time freelance photographer, quickly scoring big-time clients like Barbie, Abercrombie, and Condé Nast.

“Seeing my work in major campaigns and on billboards definitely made me feel like it was the right decision. While I don’t define my work by awards, being named an Adobe Rising Star was a meaningful milestone,” the photographer tells PetaPixel.

For Neubauer, photography is about much more than making a living, it is about giving people the opportunity to be seen.

“As a photographer with a disability, representation in photography is really important to me because everyone deserves to see themselves reflected in the world. For those who are often overlooked or misrepresented, being in front of the camera can be a powerful experience — one that affirms their presence, identity, and worth.”

“My goal is to create images that not only honor their stories but also challenge outdated narratives, making space for more diverse and authentic representations.”

Through her camera, Neubauer connects to her subjects.

“Every person I photograph leaves an impact on me, and their stories stay with me long after. The inspiration for Ashes from Stone comes from both personal experience and a desire to broaden representation in visual storytelling. Living with a disability, I know how often assumptions dictate the way people are perceived. Rather than framing difference as something extraordinary, I want to create a body of work that shifts the focus from how people are ‘defined’ by others to how they define themselves. I approach this work with an understanding that the world isn’t always designed for everyone, yet people continue to navigate, thrive, and reshape conversations around ability, gender, and inclusion. It’s incredibly meaningful to me to create a space where people feel valued and represented, and I’m grateful for the opportunity to share their stories with the world,” Neubauer says.

As she has continued to grow as an artist and turn her lens toward people who have historically been ignored, Neubauer believes the world has become more inclusive, but there remains much work to be done.

“There’s been a noticeable shift in terms of social movements, representation and conversations about diversity, equity, and inclusion. More marginalized voices are being heard, and I also think there’s a growing push for acceptance and accessibility,” Neubauer says. “However, in my opinion, the journey isn’t linear, and challenges like systemic inequalities and discrimination still persist.”

The award-winning photographer believes photography is immensely powerful and can improve the world.

“Photography can capture raw, untold stories, shed light on important social issues, and challenge narratives. Photography has the ability to evoke strong emotional responses, educate people on unseen realities and build empathy. By framing issues like poverty, injustice, and climate change, photography can bring these topics to the forefront of public consciousness, making them more urgent for global action. It holds the potential to shift perspectives and inspire change in ways words sometimes can’t,” Neubauer concludes.

Image credits: Priya Suresh Kambli, Jennifer Osborne, Koral Carballo, and Anna Neubauer. Each photographer is credited in the individual image captions. Photographs provided courtesy of the Leica Women Foto Project Award.