Photographer Reveals What a Particle Accelerator Looks Like from Inside

If you’ve ever wondered what an electron sees as it whizzes around a particle accelerator at the speed of light, then one photographer has made it possible.

Charles Brooks specializes in capturing the inside of musical instruments. Eugene Tan, the Senior Accelerator Physicist at Australia’s Nuclear Science and Technology Organisation (ANSTO), is familiar with Brooks’ work thanks to his love of music and approached the photographer with an idea.

Tan wanted Brooks to photograph a new component due to installed in the Australian Synchotron, a type of particle accelerator roughly the size of a football field. It accelerates electrons to nearly the speed of light. The light is millions of times brighter than the Sun across a wide spectrum, from infrared to hard X-rays, and is studied by researchers in a range of scientific fields.

The new cryogenic undulator component that Brooks photographed was only accessible for a few days. Tan had the bright idea to utilize Brooks’ skill when the window of opportunity was open.

“This was an instant yes for me,” Brooks tells PetaPixel. “It ticked so many boxes: I’m always drawn to photographing hidden or complex spaces, and this was one of the most intricate objects I could possibly shoot.”

Once sealed, the cryogenic undulator will be cooled to minus 123 degrees Celsius (minus 189.4 degrees Fahrenheit) and placed under a heavy vacuum where it will remain for decades. The shot was now or never.

“I was fascinated by how the undulator operates in a way that mirrors the instruments I usually photograph,” says Brooks.

“In a violin, bow pressure causes the string to vibrate, which makes the body resonate and create overtones, what we perceive as beautiful sound. In the undulator, something similar happens but at the speed of light instead of sound.

“Powerful magnets vibrate electrons as they speed through the tunnel, creating overtones, not as sound waves, but as incredibly intense laser-like X-rays. These X-rays are then used for research across various scientific fields.”

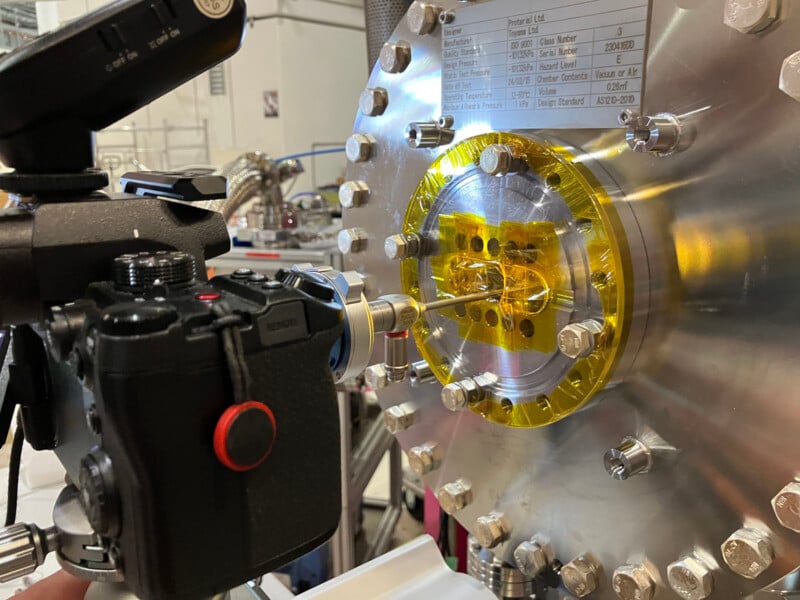

Brooks used a Panasonic Lumix G9 II which has a Micro Four-Thirds sensor. “This choice was deliberate,” the photographer explains. “Its flange distance allows me to adapt more lenses than I could with a full-frame camera.”

The New Zealand-based photographer used German-made Storz endoscopic lenses which are designed to capture video on much smaller sensors. Brooks had to experiment with “dozens of adapter and magnifier combinations” to ensure the image circle covered the sensor.

“My adapter setup is constantly evolving as I refine my techniques for better resolution and sharpness,” he adds.

The shoot was not without significant challenges. For one, super magnets inside the machine could potentially suck in his camera lens and a team of engineers had to test his gear for magnetism before the shoot began.

“They had to partially disassemble the cryogenic undulator for access, stabilize its temperature and pressure, and test my lenses for magnetism,” says Brooks. “Lens and light placement had to be carefully planned in advance, this wasn’t a situation where I could just get in and figure it out on the fly.”

Then there was the editing process. Brooks used the focus stacking technique to get his images sharp because of the limited depth of field that micro lenses typically have when photographing subjects very close to the camera.

“The editing was demanding: involving focus stacking, panoramic stitching, and dark frame subtraction. However, after many similar projects, I’ve refined this process significantly,” Brooks explains.

“The highly reflective surfaces inside the undulator actually worked in my favor, as they provided more light than I usually get when photographing musical instruments. This meant I didn’t have to push the ISO as high as usual, quite a relief, considering my endoscopic lenses function at approximately f/220 once adapted and magnified.”

And that is correct, by the way, the aperture really was f/220. His final image consisted of 120 frames.

“I want to say thanks to ANSTO and Eugene Tan for making the shoot possible,” adds Brooks.

More of his work can be found on his website and Instagram. For information on ANSTO, head to its website.

Image credits: Photographs by Charles Brooks