Social Media Platforms Are Trying to Prove Fake Images the Wrong Way

![]()

There’s a clear need for a consistently effective way to tell if an image is fake on news and social media. However, current implementations of fake-detection technology have missed the mark and can potentially undermine the more effective tools that will undoubtedly arrive later.

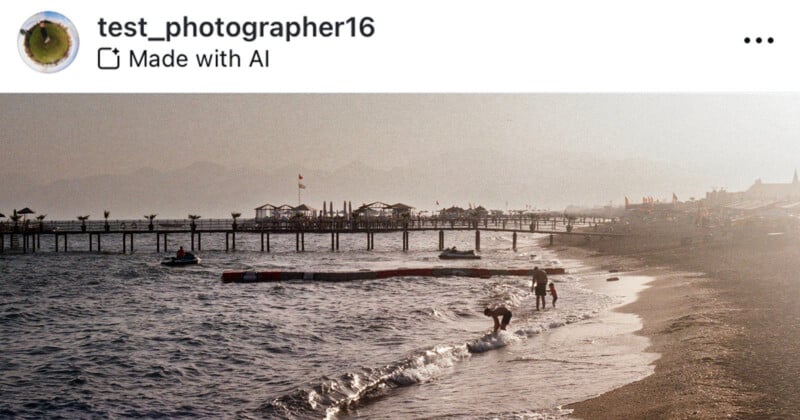

One of the most notable “offenders” so far has been Meta, the parent company of the hugely popular social media platforms Facebook and Instagram, plus the Twitter/X competitor, Threads. In May, Meta’s “Made with AI” tag on Instagram made waves for being remarkably ineffectual, and it proved too common to be unfairly dinged for fake photos and too easy to bypass the checks altogether intentionally.

More recently, on Facebook, where many people — rightly or wrongly — receive their news, the platform mistook a real photo of the Trump assassination attempt on July 13, 2024, as fake.

In the case of Instagram’s “Made with AI” tag, metadata analysis was involved, which didn’t reliably account for all photo editing tools and how people, especially photographers, use them. Meta has already reversed some of this, putting different tools back into the oven to cook a bit longer.

The issue with the Trump photo on Facebook is a bit different. Someone edited an image of the immediate aftermath of the assassination attempt, making it appear like the Secret Service agents surrounding Trump were smiling. This is a minor change at an overall pixel level, impacting a tiny portion of the overall image. However, on a narrative level, it is a significant edit that entirely changes the nature of the important real-world event. Fake pictures like these have substantial disinformation potential. They’re insidious.

So, when Facebook inadvertently labels real, unedited images fake, it is, at the very least, an understandable overstep. Most people agree it is important to prevent edited images of newsworthy events from being spread unchecked everywhere.

![]()

The other side of that coin, though, is that when a fake image check system fails by mislabeling real photos as being fake, which has happened on Meta’s two most prominent platforms in the last few months, the door is opened for two dangerous things to occur.

The first is that people think Meta has some agenda, sowing distrust in the platform’s systems by virtue of questioning its motives. The second and arguably more dangerous potential outcome is that people lose faith in image fact-checking systems altogether.

If society throws its hands in the air, saying, “Who knows what’s real and what’s fake? It’s impossible. I’ll believe whatever I want,” we collectively have a problem. Reliably accurate information is vital, especially regarding global events that can impact millions and even billions of people. The truth is a powerful shield against propaganda and intentional deception, but poorly implemented automated fact-checking systems introduce cracks in the armor.

This is not meant to be a Meta-bashing article, as the company is not the only offender, even if it is the highest-profile one. There’s something inherently problematic about all fake check-type systems for AI-generated and edited photos. With how good technology has gotten, it is complicated to determine reliably when an image is fake.

Without every single photo editing software and AI image generator implementing some digital marker that is impossible to remove, I don’t think it’s overly pessimistic to believe these systems will fail. It’s also safe to say that such a system isn’t anywhere near happening.

What is left to do if current image checks are unreliable and a potential solution is all but impossible?

The Path Forward Requires Shifting Focus Away from Trying to Prove Something is Fake and Toward Being Able to Show When Something is Verifiably True

While it can feel uncomfortable at first and seemingly not do enough to deal with emerging AI technology, the correct approach is to prioritize labeling images as verifiably real rather than worry about whether something is fake.

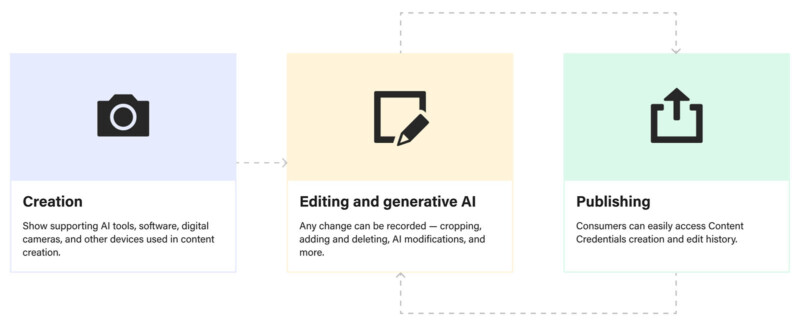

This is the approach that the Content Authenticity Initiative (CAI) takes with its C2PA standards. While that system was devised well before AI image generators spread like wildfire, it remains a promising way to securely maintain the provenance of authentic images.

In an ideal world, on news and social media websites, there would be an easy, instant way to see if an image is verified, providing users a way to see when, where, and how an image was captured and what, if any, editing has been done to it. Unlike regular metadata, this data cannot be edited. If unbroken information is unavailable, the image cannot be verified.

It’s essential to fight the temptation to conflate systems that try to detect a fake image and those that aim to show when an image is undeniably real. While the goal may be similar in both cases, the path forward is dramatically different, and the latter seems much more effective.

Methods of checking for fakes will be in a constant arms race with technology, and mistakes are inevitable. A system that can show when an image is real — and say nothing of whether an unverified image is real or not — may not have the reach some people demand, but it also will not screw up. A fake image will never be labeled as real. Sure, a C2PA-based system can’t say anything about photos without the necessary data.

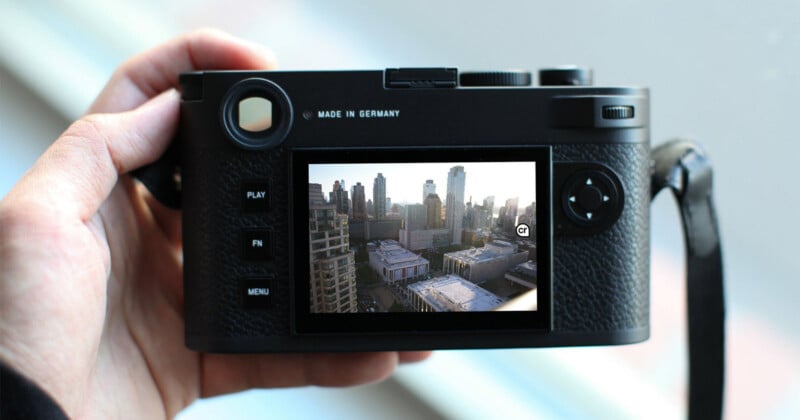

With increased implementation of the tech CAI is working on, including camera-level C2PA tools and inclusion on websites and social media platforms, a world where many of the most impactful images have a verified chain of information is not impossible. If enough photographers and editing apps have C2PA tools, major journalistic institutions could start requiring it for all photos, and then social media platforms may not be far behind if they can prioritize accuracy over other concerns.

At this point, C2PA adoption has been frustratingly slow. C2PA tools have only been implemented in a handful of cameras from companies including Fujifilm, Leica, Nikon, and Sony, and only in specific pro-oriented camera models. The technology required has not been adequately deployed and implemented at any stage of the photographic process: creation, editing, or publishing. It is possible to show when a photo is verifiably real, but it will only get more challenging to try to determine when an image is fake.

There is an immediate demand for this void to be filled, driving the half-baked, unreliable fake checks we’ve seen so far. However, the priority cannot be speed when it comes to the fight over truth in photography. The focus must be on accuracy. The framework for the technology to confirm truth in imagery already exists; it just needs to be implemented across the platforms where people get their news.

Image credits: Header photo licensed via Depositphotos.