Wax Paper Photography: Getting the Large Format Look With a $300 Soviet Camera

![]()

Anyone who has trawled through a historic photo archive knows the feeling of spotting a large-format photo. Like spotting a beautiful woman in a crowd, it’s hard to drag your eyes away. That depth and clarity, which seems to top reality itself, has only ever been possible with a film plane measured in inches rather than millimeters.

I was obsessed with recreating the large format feel of a 10×8-inch film camera until the reality – scores of dollars spent for each frame and days of waiting to see the results, killed the dream.

Then I saw the June 2021 PetaPixel article on Ukrainian photographer Alexey Shportun, who partly recreated the large format look.

By replacing the plane where film usually sits with a white wall, Alexey then photographed the projected image with a digital camera looking inside the large format camera.

An important sidenote here — the credit for this idea should really go to Zev Hoover who perfected a more advanced version of the same technique years earlier using a Ukrainian-made lens, but whose breakthrough seemed to go largely unnoticed.

Soon after seeing the PetaPixel write-up, I bought a Soviet-era 10×8-inch FKD “pavilion camera” with a 300mm f/4.5 lens to test things out myself. It quickly became clear the technique showcased in that article is fundamentally flawed. The digital camera is looking at the projected image from “around” the main lens of the large format camera, so the image is distorted to the point that it’s dizzying to look at, even after severe tweaking in Photoshop. Additionally, the focus point is limited to one horizontal section of the image.

On the Facebook post beneath that PetaPixel article I wondered publicly: Instead of photographing a white plane with a digital camera poked into the front of a large format camera, why not capture the image projected onto translucent material from the back under a light-proof cloth? I received a couple of answers as to why it wouldn’t work, but none made sense to me.

I started by playing around with different materials to photograph the projected image on. First came the obvious frosted glass – a non-starter due to an intense hotspot and the grittiness of the image. Then I attempted to coat a pane of clear glass with oven-melted wax (a kitchen disaster).

The eureka moment finally arrived when I pulled a sheet of baking paper over the back of the Soviet camera where the film would usually sit. I remember the following moments well. My daughter, then a little over one-year-old, was playing on the floor next to me as I ducked under the black cloth to focus the Soviet camera and then photograph the crinkly paper with my Lumix GH5. When I emerged and looked at the photo I’d made of my barbeque outside on the terrace I was stunned. “YES!” I exclaimed.

My little girl was equally surprised at seeing me, fist in the air, making such a loud noise. “Yass!!” she echoed — arguably her first word in English.

After a little more tweaking I ended up at the ropey but functional point where the technique stands today. I use artist tracing paper stretched across the film plane and held in place with double-sided tape. I photograph the paper from inside a lightproof cloth tunnel with a handheld Lumix GX9 and a 17mm f/1.2 Olympus lens. The cloth is held in place with bulldog clips and my teeth.

One thing worth noting: That super fast lens is essential. Even in a sun-drenched scene it’s hard to get a shutter speed faster than 1/200th so getting a sharp image on an overcast day or in the shade can be a struggle with anything slower than f/2.0.

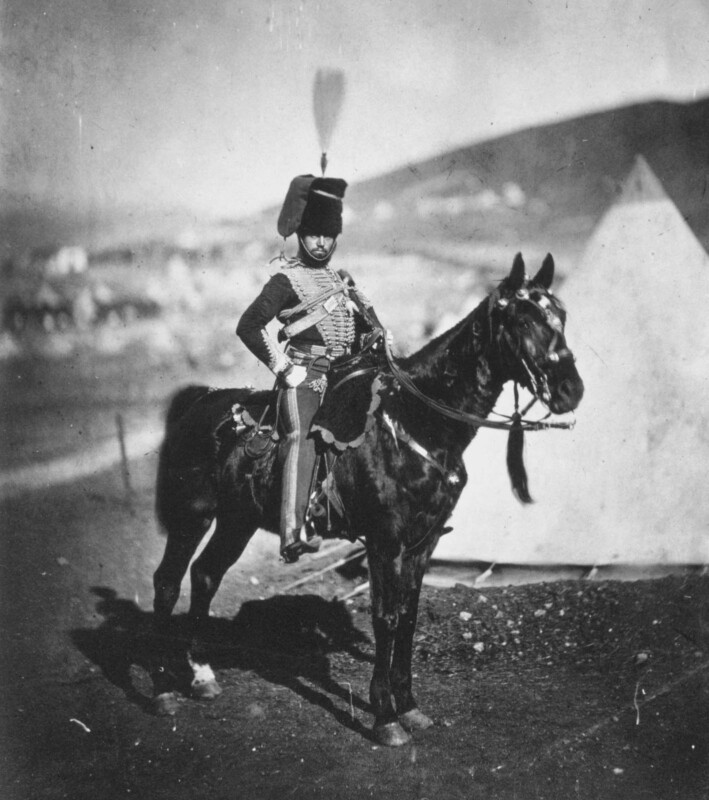

The first outing for this technique was in the summer of 2021 in Ukraine. I used it on a couple more shoots, including in Armenia, but perhaps the perfect subject for the camera was the 2023 Zheravna festival in Bulgaria, where no technology is allowed inside the venue (they let me in with the giant, antique camera), and entry is only permitted for those wearing traditional or historic clothing.

With that I’ll stop talking, and unroll the photos I made that day. I will answer as many questions about the technique as I can, as I continue to iron out the technique’s many flaws. Enjoy the pictures.

About the author: Amos Chapple is the senior photo correspondent for RFE/RL and is based in Prague. You can find more of his work on his website and Instagram.