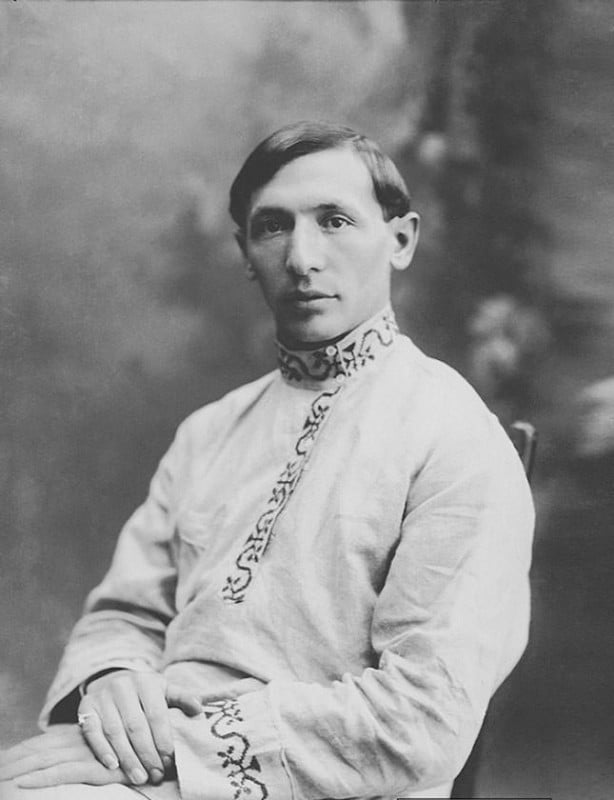

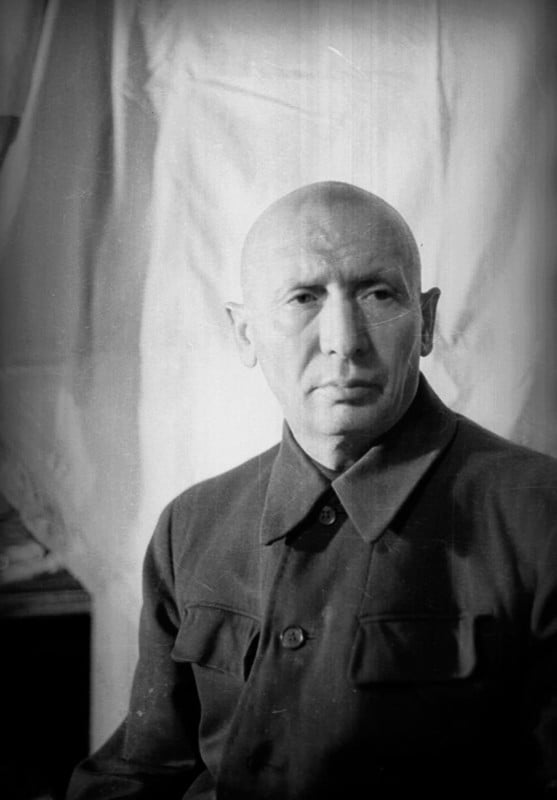

The Forgotten Photographer of Soviet Uzbekistan

![]()

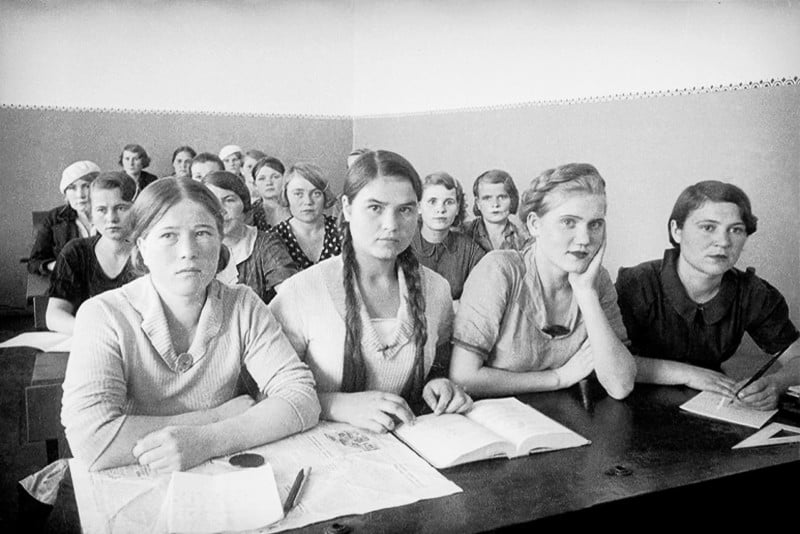

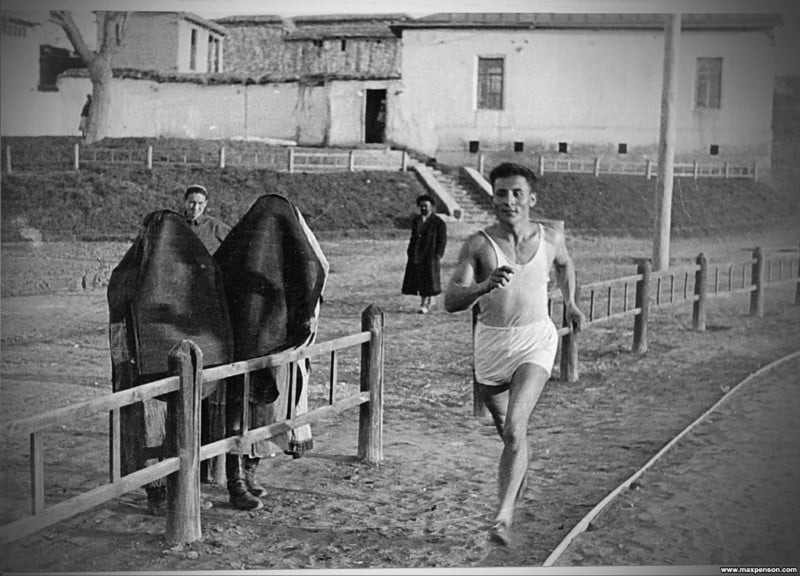

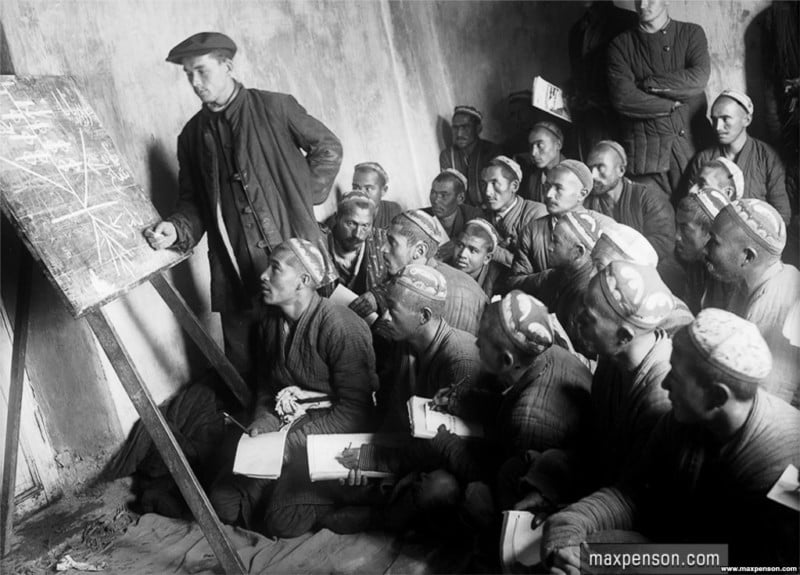

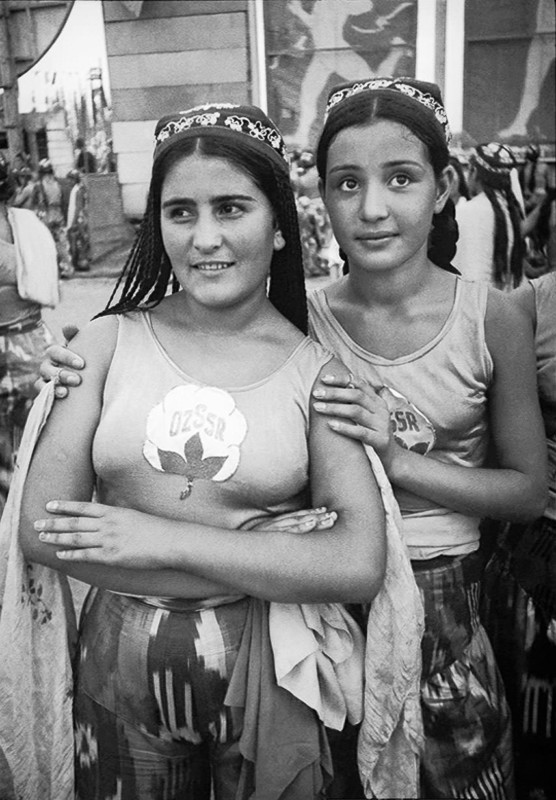

As Central Asia was transformed under Soviet rule, one man made a remarkable record of life in the fledgling Uzbek S.S.R. before being driven from his career and toward tragedy.

About the author: Amos Chapple is a Kiwi photographer who makes news-flavored travel photos. He started off at New Zealand’s largest daily paper in 2003. After two years chasing news, he took a full-time position shooting UNESCO World Heritage sites. In 2012, he went freelance but kept up the travel. Since then, he has been published in most major news titles around the world. You can find more of his work on his website, Facebook, and Instagram. This article was also published Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty.

Discussion