On Hate Mail: When Your Photography Attracts Death Threats

There’s only so many times people can threaten to kill you before you start to wonder if they might be serious.

And it’s earned me, in those several weeks since, about two dozen different pieces of hate mail from strangers: people accusing me of various moral crimes, people writing to share their favorite ethnic slurs and, yes, several who have threatened to kill me.

The good news: at least nobody has knocked the photography.

It all began a few months ago when – and you’re about to read this correctly – a white supremacist showed up at an exhibition I had up at a New York City museum. What was he doing there? I don’t know. How did he get in? I don’t know. I assume he was on his way to the fabric store to buy fresh white sheets and got lost. Perhaps he just needed a bathroom, desperately. Nevertheless, somehow or other a person who hates just about everybody ended up at my show, and started a thread about it on a white supremacist website.

It’s an… interesting read. I’ve seen it. What these folks lack in tact, they more than make up for in what we’ll call improvisational spelling; the frontier of their supposed supremacy also ends far, far short of standard grammar, as well. But there they are, all in a group, chatting as casually about this as you or I might talk about whether the avocados in front of us at the supermarket are ripe. (They’re not. They never are.)

My name, the hotsy-totsy-nazis insist, is of good Dutch provenance; surely, I must be a race traitor. But my Facebook photos – which someone felt a need to trawl through and repost – betray a face of great ethnicity: a proboscis that enters a room unfashionably earlier than I do, a tan that rises when even gently frisked by the sun. The jury being out, I begin to receive notes (largely by email) accusing me of, well, everything: I’m a pawn of the Jewish conspiracy to take over the world, I’m an embarrassment to the Aryan people. One oddly woke supremacist says I shouldn’t have done this project because I’m obviously not Jewish. Another implies I shouldn’t have done this project because I’m obviously Jewish. I’m the lying media. I’m the lying media. I’m the lying media. Fake news. Fake news. It’s surprising I’m able to sit at all, what with the problem of my inextinguishable pants.

On the day of the book’s release, a gentleman using a nom de plume/nom de doom sends me an email accusing me of being part of the “zog conspiracy,” which I have to look up after I confuse it with Superman nemesis General Zod, with whom I have never ever conspired. His subject line? “Invited to Death,” which sounds like the name of an absolutely terrible punk rock band. Invited to Death: a bunch of vaguely smelly guys who growl into a microphone about how terrible life is, before returning to life living in their mothers’ basements.

You know: just like the people who send hate mail.

![]()

I do not think many photographers receive angry mail from strangers. I certainly hope most don’t. But I suspect I’m not alone; there is a presence to photography, a frequent theft of agency that perhaps invites insult. And I – a fairly non-threatening, friendly presence in the photography world – have to be pretty far down on the list when the universe is handing out nastygrams.

And yet. My first book, on American poets, would occasionally earn a note from a poet who’s been excluded— sometimes, a reminder that some people can push a noun against a verb to blow something up, but more often a clear and inarticulate demonstration of why the person was excluded in the first place.

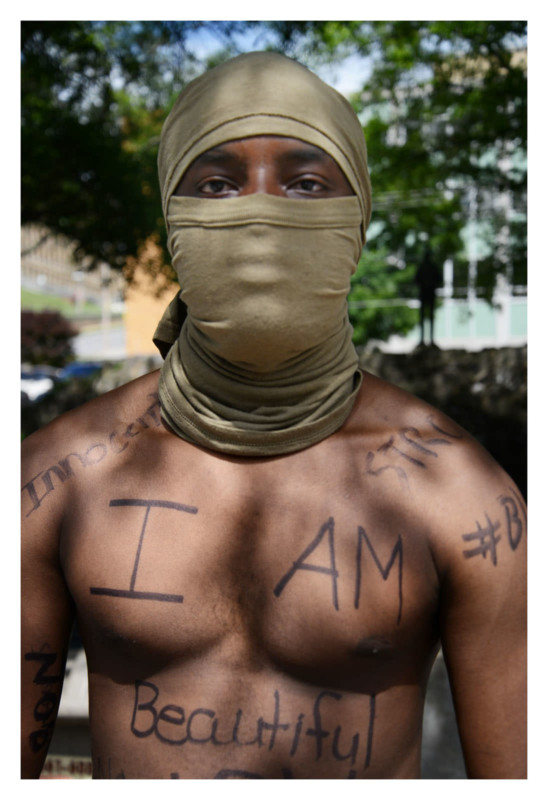

When, two days after the murder of George Floyd, I made a photograph of a Black protester on an Arkansas street who I’d personally seen spend his day being called terrible things- that went fairly insanely viral, somebody went to the trouble of setting up a fake account on Twitter (an online forum for hate speech) just so angry people could have the satisfaction of having somebody to holler at.

Strangers on Reddit – where I’m also not – took plenty of time to try and discuss the matter in just the most similarly dulcet tones. When I photographed the protester, I’d seen plenty of bikers ride by – on purpose – to yell obscenities at the protester and his friends. Turns out, some of the bikers, too, had the time to tell me they were upset about my mention of that.

A week later, the phone rang while I, national menace that I am, was sitting on a bench outside a Cinnabon. When I answered it, somebody in Arkansas recited only the address of my tough-guy veteran father and immediately hung up. You can imagine with me the scene that might have become: a bunch of people standing out in the hallway of my father’s apartment building, watching a good old boy struggling to pick up his teeth with his broken fingers.

This sort of thing is, of course, nothing new. I’m sure there were mayors all over Sumeria with waste bins full of angry tablets delivered by soon-to-be arrow-pierced couriers. And, on a certain level, I’m even personally sort of habituated to the vitriol of perfect strangers – my annual year-end post has always earned a little perennial weird mail, and before PetaPixel instituted a wise filtering policy on reader comments, articles including my work were often greeted on departure by the usual sort of comments from toplofty readers proclaiming, for all and sundry, my lack of worth.

I’ve been writing the piece you’re currently reading for about a month. Teetering back and forth, weighing the pros and cons about whether to weigh in at all, I sat down for conversations with about eight different people I know who I’d heard received lots of negative attention: museum curators, photojournalists, writers, a politician. But the one that struck closest was a comedian being dead serious.

I first came to know the popular comedian Steve Hofstetter during a photo shoot a few years back; the humor artist is himself no stranger to the vagaries of internet hostility. “Fame is a fickle food,” wrote Dickinson, and few spend as much time at the buffet as Steve: he’s been so thoroughly vetted by the internet commenters that the FBI have had to be called in on at least one occasion. “The thing about it,” Steve said during our shoot, “is that the people who do this – who leave the comments, who send the mail – they’re never creators. They’re never people who’ve actually done anything – who’ve made the art, who’ve written the book, who’ve gotten on the stage.”

Steve and I have since become friends – in spite of our clear contemptibility to the masses – and when the current exhibition and book came around I sat down with him to chat a little about hate mail. At the time, I was getting it on all sides: the revenants of ignorance had come out of the gutters to tell me I need to stop serving *waves hand vaguely* “the Jews.” To complain that the book is not Jewish enough, or too Jewish, or that Jews exist at all. To tell me that I need to address the situation in Israel, as if that is something that I, an American photographer, am suddenly able to do. As if I could pick up my specially-made blue and white phone and just say “Hi, is this the Knesset? Y’all don’t know me from the dark side of your butt cheeks but some guy in Williamsburg just emailed me ‘free Palestine’ so I think you should do that. Is there a “free Palestine” button on your desks? If so, please press it. Thanks.”

It is difficult to underestimate these folks, but when the white supremacists started posting about me – something Hofstetter had leap at him, as well – I wanted to talk about the implications to, I suppose, the art of the work.

Years back, yet another white supremacist site started a thread on him, Hofstetter’s life was turned upside down. “For a couple months, they were saying just horrifically terrible stuff,” he recalls. One sympathizes. “I get through my day without thinking about it much. What worries me is not my safety – a comedian in a bar has never been killed. My ego doesn’t say I’m important enough to be the first.”

“My response is to keep going,” says Hofstetter, “and get on stage and ask why Britney needs a conservatorship, and Kanye doesn’t.”

We live in an age, now, where everybody has a microphone and, more importantly, everybody has a megaphone. The question, for me, becomes: why bother? I do not understand the people who spend their time waging hate campaigns; I do not understand the people who take the trouble to email random photographers who make books about American pluralism, or chase around comedians who spend most of their time trying to dodge hecklers in taverns. I do not understand why they do this with their one and precious lives instead of hanging out in the park kissing people, or going to a ballgame. I do not understand the folks who hang out on Tumblr and Twitter and Reddit and photography websites to leave comments about how much they hate what they see.

It seems significant that it never seems to come from the people who’ve actually done: who’ve suffered the fear of putting their work into the world, who’ve written an article, who’ve gulped as they put their byline on something, who’ve stepped out on a stage. The people who write me to tell me they hate what I’ve written are never writers. You can tell, if for no other reason, by their spelling.

“It is extremely easy for someone who does not create to tear down those who do,” muses Hofstetter. I find that the practice of creating creates sympathy for those who do. It’s Dunning-Kruger; the less you know, the easier it is to misunderstand. Those who can’t, criticize.”

There’s one difference between he and I – and seemingly all of the people who I spoke with while thinking about this article. I do not respond. They all seem to. “I choose to engage with the comments because of the algorithm,” Hofstetter admits. “Because of the engagement. But it’d be great if the algorithm didn’t reward that.”

Part of this current trend is entirely due to the anonymity of the internet – most of the emails that have come my way arrive from fake email addresses and fake names. Part of it is driven by the fact that grown adults can now get the adrenaline of the playground insults they used to get when they were first children, without any of the repercussions or consequences. But part of it is something larger:

Hate mail is a good thing. That is not, of course, empirically true; it’s terrible. And I can assure you, that it’s not pleasant; and I can assure you that I, like the 140 Holocaust survivors I’ve met, choose to respond to hate with some level of humor, as well as some occasional brobdingnagian vocabulary that our detractors can’t quite understand. But more importantly, it’s this: artists, writers, creators – the goal is to start the conversation. The goal is to bring in the greater response. To turn the eye to empathy. To broaden the viewer, to introduce the new perspective. The person who writes the hateful email, the person who starts the seventeen-piece nonsensical Twitter thread, that’s a person who has, at the end of the day, been given a perspective other than their own but cannot process it.

Hate mail is, in a way, a reward. Those photographers who make calendars of nice pictures of puppies have overserved bank accounts and empty inboxes.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

In my own case, all I did was write a book about how America is large, and contains multitudes. How people can overcome trauma. How folks of many religions, backgrounds, orientations are the thread that stitches together the national fabric. And the mail means one thing: there’s enough truth in it that the people who are bothered by it must resort to shouting; that to avoid a conversation they don’t like, must resort to banging their shoe on the podium.

That the only way to fight the truth is to try and scare the person who’s telling it. Few things in this world are better confirmation that you are doing something right than somebody otherwise unremarkable taking huge swaths of their mediocre day to tell you that you’re doing everything wrong.

Perhaps it is a good question in one’s artistic practice to ask “would my work bother nazis?” It is a good question in one’s artistic practice to remember that the thing about hate mail, perhaps, is that you should learn to love it.

And if you can figure out how to do that: hey, drop me a line. Tell me how.

The opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author.

About the author: B.A. Van Sise is an author and photographic artist focused on the intersection between language and the visual image. He is the author of two monographs: the visual poetry anthology Children of Grass: A Portrait of American Poetry with Mary-Louise Parker, and Invited to Life: After the Holocaust with Neil Gaiman, Mayim Bialik, and Sabrina Orah Mark, which will be released on January 27th. He has previously been featured in solo exhibitions at the Center for Creative Photography, the Center for Jewish History and the Museum of Jewish Heritage, as well as in group exhibitions at the Peabody Essex Museum, the Museum of Photographic Arts, the Los Angeles Center of Photography and the Whitney Museum of American Art; a number of his portraits of American poets are in the permanent collection of the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery. He has been a finalist for the Rattle Poetry Prize, the Travel Media Awards for feature writing, and the Meitar Award for Excellence in Photography. He is a 2022 New York State Council on the Arts Fellow in Photography, a Prix de la Photographie Paris award-winner, and an Independent Book Publishers Awards gold medalist.