Camera Traps with AI Technology Recognize Mountain Lions’ Faces

![]()

Researchers have figured out a way to take headshots of Mountain Lions in the wild and then categorize an individual thanks to artificially intelligent (AI) facial recognition.

The remarkable study uses camera traps that play a noise to pique the interest of a passing puma concolor, otherwise known as cougars or Mountain Lions, so they turn and face the camera which allows reseachers to get a clear photograph. The team can then analyze the images using an AI online application.

As one of the world’s most reclusive big cats, Mountain Lions are extremely hard to directly observe. And unlike the unique stripes on a tiger, for example, the lack of distinguishing features on the body of a Mountain Lion makes it difficult for researchers to identify and track individual animals.

However, it’s a different story when it comes to a Mountain Lion’s facial markings — which is what led researcher Peter Alexander and his team to develop non-invasive camera traps enhanced with facial recognition to take close-up photos of the secretive animals’ faces.

![]()

In an interview with Scientific American, research biologist Peter Alexander, who is based in the greater Yellowstone National Park area, describes the difficulties of getting information about the mountain lion population with the traditional camera traps used by researchers.

AI Facial Recognition Camera Traps

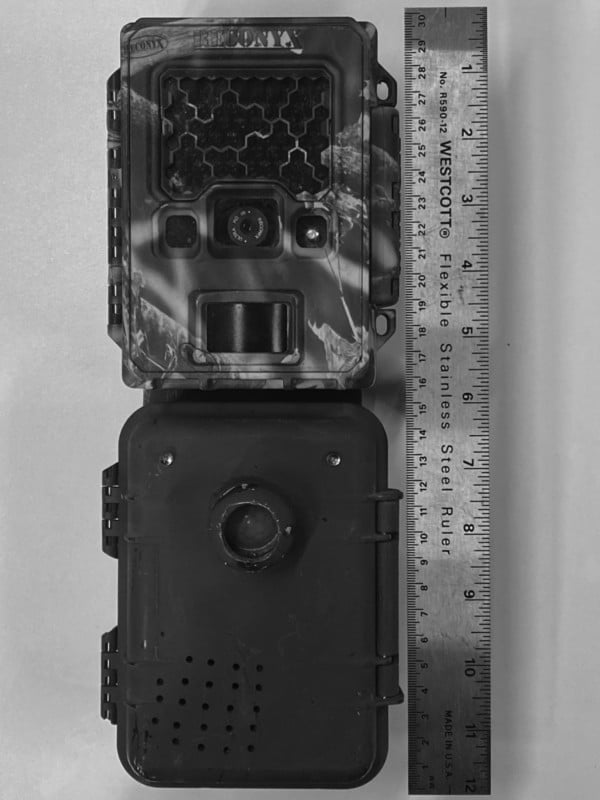

The camera traps, which are about the size of a shoe box or even a coffee cup, are attached to something that’s along the animal’s regular path, like a tree that the Puma has territorially scraped. When motion is detected, the trap gets triggered, resulting in a snapshot of the mountain lion as it strolls by. The cameras even have an infrared flash so that nighttime photos are captured without disturbing the animal.

Researchers around the world use this type of tool to estimate population numbers and the overall abundance of species. They comb through the images, sometimes using machine learning algorithms, and analyze them to identify individuals.

Tigers are the “classic example” of using camera traps for ID’ing individual animals, says Alexander “because those stripes, they’re like a fingerprint.”

![]()

But nearly all mountain lions around the world, with exception of distinguishing things like scars, have light, sandy-colored fur down their sides. This lack of unique coloration on the sides of their bodies means that researchers like Alexander are usually unable to tell if one puma crosses a camera trap five times, or if five individual animals pass by.

But on the other hand, if you can get a close-up image of a Puma concolor’s face, it’s far more helpful. “There’s a lot of detail in whisker patterns and all sorts of stuff. They are beautiful,” explains Alexander.

So, Alexander and his team decided to capitalize on the dramatic facial features of mountain lions. The researchers added a few gadgets to their camera traps so that when motion was detected, a cougar kitten call was played. This noise reliably piqued the interest of passerby pumas so that they looked up long enough for the camera trap to grab a face shot.

![]()

Five independent investigators reviewed the puma headshots and attempted to ID the individual animals. Compared to the traditional side-angle camera trap, the new attention-grabbing device was about 92% more accurate.

This study, which was published in the journal, Ecology and Evolution, earlier this year is an important step on the path to being able to more confidently identify and track animals, in a scalable way. Snapping headshots of mountain lions also opens up new opportunities to involve AI techniques. This tool, which is similar to the facial recognition technology used by airport security, could expedite the image analyzation process for researchers.

![]()

Alexander says that this new camera trap method could be used for tracking other animals that lack distinguishing side colors but have unique features elsewhere. This includes vulnerable species like wolverines, pine martens, and even grizzly bears.

“That could be a really useful technique in the future. There have been a lot of other facial recognition studies done on animals, but it’s never been with a camera trap. So that was kind of the unique thing about this study was merging these two ideas,” says Alexander.

Image credits: All photos by Peter Alexander.