Exposed: Aline Smithson, the Ambidextrous Photographer

![]()

When I first discovered the rather active analog photographer, journalist, and educator Aline Smithson, I felt that I have been standing in place with one hand tied behind my back. I spend my photographer energy thinking about the project that’s directly in front of me. One project at a time.

Aline, on the other hand, seems to be juggling (yes, I am mixing metaphors) multiple projects at the same time. Aline is a published visual artist, workshop leader, Lenscratch founder, exhibition curator and editor based in Los Angeles.

And, importantly, someone who turned pandemic-born isolation into humor.

Let’s dig in.

Peter Levitan: Aline, you are rather ambidextrous. You use both hands and the right and left sides of your brain to manage your photography career. Before we get into the myriad types of programs and projects that you create, how and where did you start your photography journey?

Aline Smithson: Thank you, Peter! It is an honor to be in conversation with you and the PetaPixel audience. I’m going to give you the long version as all that we do in life, the stew of who we are, informs the work that we make.

I grew up in Los Angeles and was always interested in anything to do with the arts – drawing, painting, sewing – and I loved reading fashion magazines. My father was a hobbyist photographer with a darkroom in the basement, and my uncle was an editorial photographer, but I wasn’t bitten by the photography bug until many years later.

I studied art in college with a focus on painting but also learned printmaking, photography, video, and more. I created large colorist oil paintings and was very influenced by California painters like Ed Ruscha, John Baldessari, Richard Diebenkorn, and David Hockney.

After college, I moved to New York to make my way as a painter, but the art world was a difficult nut to crack, and an opportunity came up to shift gears and work in fashion. For the next decade, I was the Fashion Editor for Vogue Patterns and Vogue Knitting magazines and catalogs—a position that I was totally unprepared for, but I jumped in feet first. I was responsible for19 publications a year, coming up with story ideas, selecting fabrics, and working with dressmakers to create the clothes, and then setting up photo shoots, traveling the world with significant photographers such as Mario Testino, Patrick Demarchelier, Arthur Elgort, and even Horst.

It truly was a dream job that included some form of creativity each day. The art director and I edited all the film, and happily, it was a skill I brought to my own work. I also learned a lot standing next to a wide range of photographers – how to work with people, how to create a happy and productive set, how kindness and levity go a long way, and I also discovered personalities that I wasn’t interested in working with again.

I eventually moved back to Los Angeles and started a family. I was now the family documentarian and decided to take a photography class to learn how to better use my camera. It was in that class that I discovered my uncle’s 1960’s twin-lens 2.8F Rolleiflex (which I still use today), and it completely shifted how I see.

I realized I could make art with a camera. After that, I never looked back. I spent many years happily anonymous, learning my craft and the darkroom, making work just for me. I began to show my work and just kept going. Eventually, I started teaching and building a community of like-minded photographers in Los Angeles.

The publication Lenscratch appears to be your bridge between your editorial and burgeoning photography career. How did that idea develop?

In 2007 I started Lenscratch, a daily journal on photography, in order to learn more about the community I was making work in. I made a vow to write about a different photographer every day. Fifteen years later, the site is still going strong. I have an amazing team of editors and we all work for free as a give-back to our community.

I’ve learned so much by deeply considering other people’s photography and thinking. We have opportunities for photographers at no cost, we offer the annual Lenscratch Student Prize Awards, and lots of features that are of interest to photographers. In December we are dedicating the month to interviews with book publishers.

I’d like to ask you about a few of your photography series. Since our memory of pandemic isolation is fresh, I find your Undercover series interesting for a couple of reasons. One, it is an unexpected view of the personal side of self-quarantining. And the second is its humorous way of allowing you to make collaborative portraits during lockdown at a time when many of our relationships became so distant. How did this idea roll out?

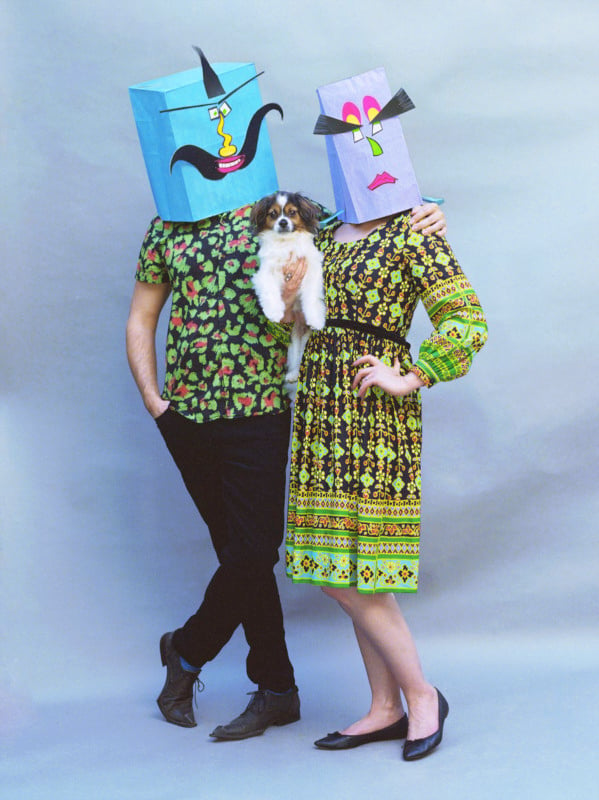

When the pandemic hit, in those early days of self-quarantining when we were scared to be around each other, I started thinking about how wearing masks and distancing ourselves was changing our social behaviors. How were we able to express our emotions when you couldn’t see one another’s faces? I began to think about masks and what they convey in certain cultures, and I remembered the fabulous paper bag masks that Saul Steinberg created in the 1950s/60s.

I decided I wanted to create a project that spoke to this moment in time with levity, creativity, and fun. I asked friends, neighbors, and family to participate. I set up a backdrop in my back yard, instructed my subjects to stand on the paper wearing their masks, and I would come out in my mask and start photographing. The shoot resulted in great hilarity as the subjects were completely covered and lost normal inhibitions of being in front of the camera. It was such a positive experience for all of us.

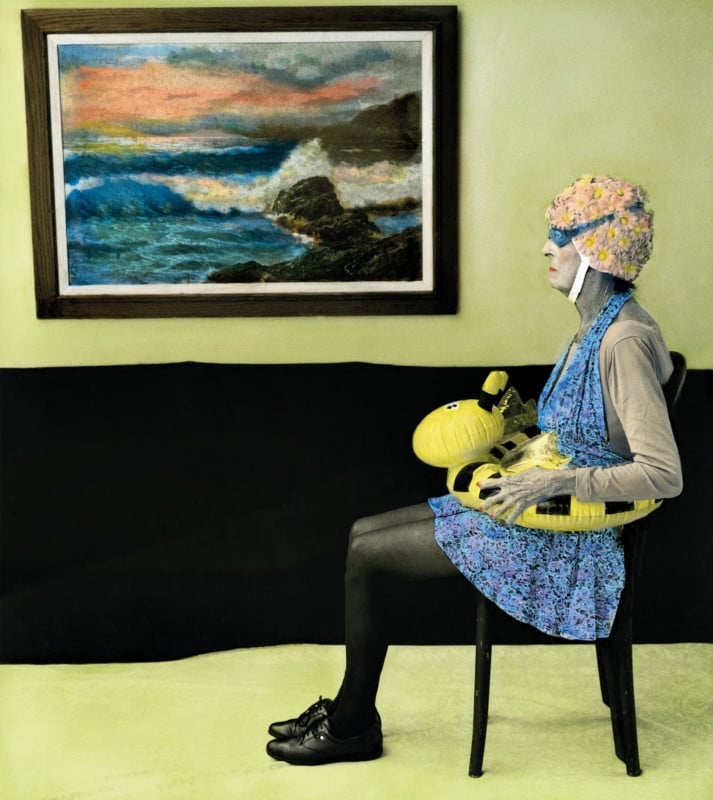

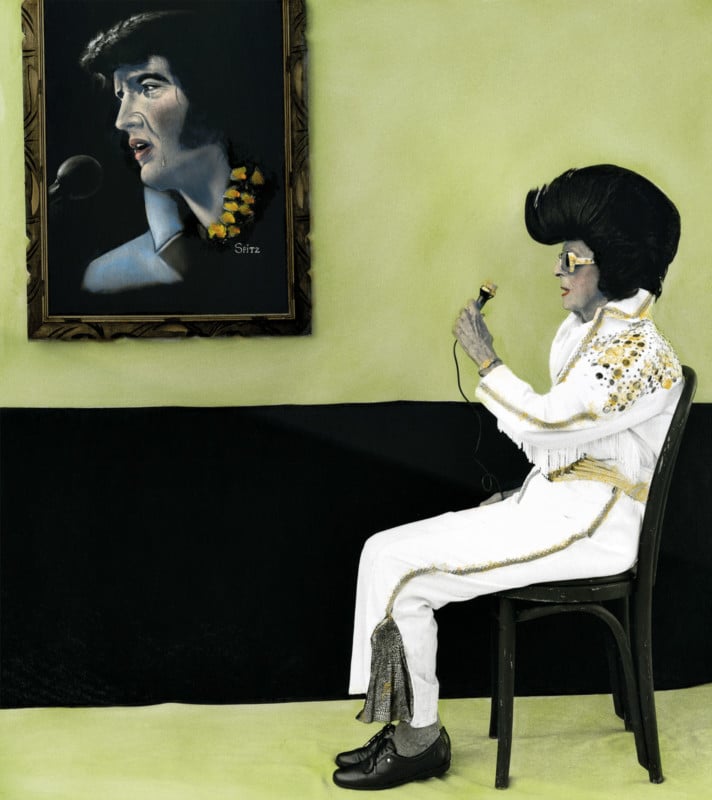

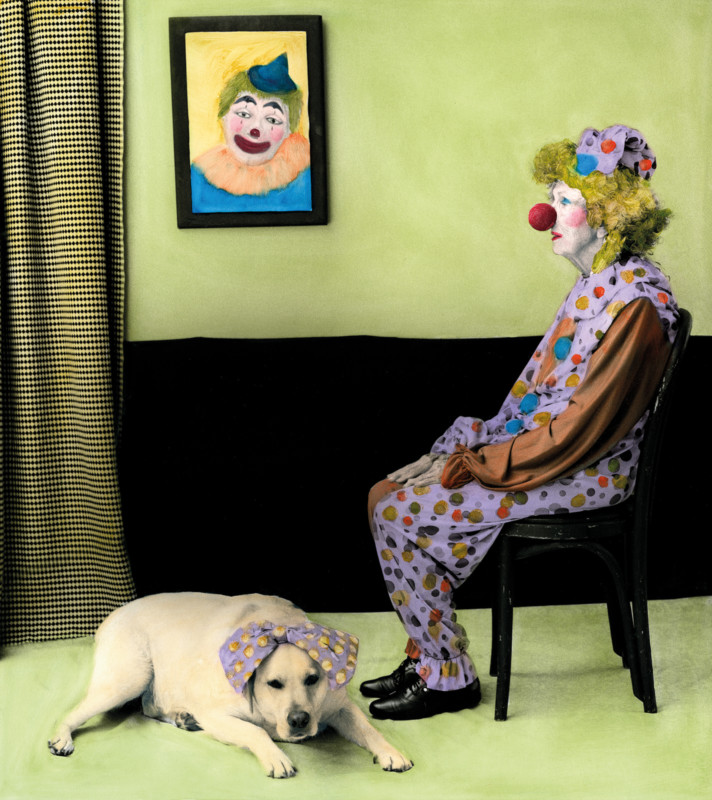

Continuing with the idea that your work leverages your personal relationships, you used your mother as the model in your 20+ image series Arrangement in Green and Black, Portraits of the Photographer’s Mother. What was the genesis of this homage to James Abbott McNeil Whistler’s iconic painting, Whistler’s Mother? Was it difficult to get your very own mother to participate?

Whistler was a painter I very much admired. The series had serendipitous beginnings – I found a print of Whistler’s Mother at a garage sale and I looked at the composition in a new light, realizing that there was potential for play and humor in recreating it. That same day at various garage sales, I found a leopard coat and hat, a piece of leopard fabric, and a cat painting – and I knew I had my first set-up. I asked my 83-year-old mother if she would be my model and it was an immediate yes.

Over two years, we created 20 tableaux – both of us had so much fun working together, and it was a joyous project since it included all the things I love: my mother, thrifting, eBay, and creating something out of nothing. My mother passed away before she saw the painted images, but I like to think of her traveling the world, as the series has been shown in Russia, Korea, China, Italy, and the U.S.

This is the series that launched my career, and it still sells the best. The pieces are hand-painted silver gelatin prints, so each time I sell one, I must print and repaint the piece. But it allows me to spend time with my mother once again.

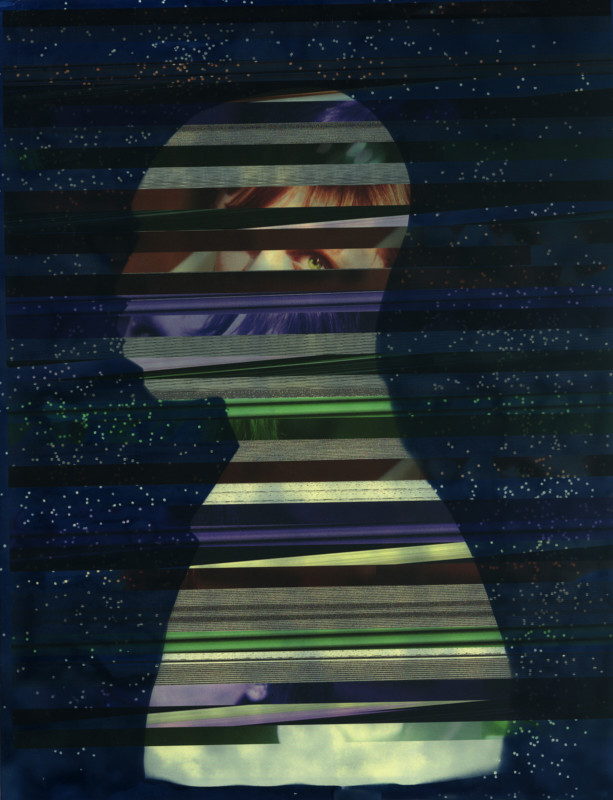

Many of us have boxes of photographs (well, some of us) and thousands of digital images on hard drives. A couple of years ago, you experienced the destruction of some of your digital files that included 20 years of analog scans. It seems that rather than cry in the corner, I’ve done this, you took this loss as a way of helping us think through the idea of loss and longevity in your Fugue State Revisited work. Are our digital files and images ultimately doomed?

When my hard drive with 20 years of scans died, of course I was bereft. But as an analog photographer, I knew that I still had the negatives. When I got the hard drive back in hopes of recovering the content, I discovered that at least half of my archive was corrupted. Interestingly, each file was corrupted in a totally unique way, as if the machine was creating a new language.

After the shock wore off, I began to look at that devastation and realized that everyone’s hard drives are going to fail at some point, that the next generation isn’t going to continue to update our archives, and that all digital imagery will cease to exist in 50-100 years. This was a profound realization, but all I had to do was to look at the music industry to understand how changes in technology moved us from vinyl to platforms like Spotify, with no tangible element that connects us to the music. How I miss album covers!

In my research about this phenomenon, I realized that institutions are grappling with this issue. The Getty Research Institute states, “While you are still able to view family photographs printed over 100 years ago, a CD with digital files on it from only 10 years ago might be unreadable because of rapid changes to software and the devices we use to access digital content.”

For this project, I printed out my corrupted scans and then, using silhouettes of portraits I had previously taken, created cyanotypes over the scan as a way to create an object that will move into the future.

You’ve produced six books. Do you think that a book of photographs might just be the best way for us to preserve our work for future generations? I think that you accomplished this by working with Peanut Press on your Fugue State book itself.

During COVID, I took a hard look at what was important to me. I realized that I wanted to tell my stories – to pass something on to my children and grandchildren that was tangible, that could move through the generations. It made me realize how important books are to create that legacy. I’m working on some smaller self-published books that I will create in small quantities that will be artifacts for the future.

So, to answer your question, yes, a book of photographs just might be the best way to preserve our work. But I also think it’s important to write our stories too. One of my inspirations is Sophie Calle’s True Stories – a small book with small stories and accompanying photography. It doesn’t have to be a grand gesture. It can be humble and still profound.

How did you manage to have one of your Fugue State Revisited images be the featured illustration in a Harper’s Magazine article? Interestingly the publication is paper based and therefore “permanent”.

The photo editor of Harper’s saw one of my images on Instagram and reached out to me. She commissioned me to make additional images, which was really exciting. I love magazines and Harper’s always makes interesting connections between text and image.

Moving back to the idea that you are ambidextrous, you are running photography workshops in 2022 at the Los Angeles Center of Photography. One of the sessions, Bringing Projects to Completion, addresses the ongoing question of knowing when we are done and it’s time to move on. How do you know when a project is complete?

Great question. I still have an interest in working on every single one of my projects, but sometimes you just run out of steam or interest. With this workshop, I hope to inspire photographers to see the potential of their projects, to consider the installation and articulation of the work. It’s more of a push to get going and get the work out. We all procrastinate when it comes to the hard (and not so fun) part of marketing the work. Many photographers don’t give the work they create the time and thoughtful effort it requires.

In respect to the workshops, how do you determine what subjects to cover?

I always teach what I wish I had learned on my own journey. As I get further along the road in my photography career, I learn more and pass on that knowledge. Certainly, writing for Lenscratch allows me to dissect artist statements, see themes in contemporary photography, and understand what makes a powerful project and presentation. I then break down that knowledge and pass on my discoveries to my students.

For one class I teach creative thinking and ways of working. In another, I demystify the fine art market and teach photographers how to get their work out smartly. I also teach about all the elements that surround photographs – the artist statement, bio, editioning, and pricing, etc. And I am a cheerleader for everyone I meet, helping them to see the potential in their work.

I never teach photographers how to make work like me, as they have their own stories to tell. I work hard to honor each photographer’s way of working.

Last question. You are a 100% analog photographer. Why?

It probably starts with the fact that I learned photography in an analog era. But as time went on, I came to revere the analog process. The unwrapping and loading of the film, metering and preparing for a shoot, hearing that clunk of the Hasselblad when I press the shutter, or the winding of the Rolleiflex as I peer into the focusing screen. And then, the wait to get the film back is always a bit like Christmas morning. It makes me feel connected to photographic history.

As an analog photographer, I do almost all of my editing before I click the shutter, and this slowed-down way of shooting means that I am really looking hard. Shooting digital is a whole other can of beans…so many of my students take hundreds of photographs of something that I might take only two or three frames of. And it means that their creativity is in the editing, not in the photographing.

As an editor, I can always spot a film image—there is a nuance to the light and color that just doesn’t exist in digital images. And finally, there is a lot of discussion about how expensive film is, which is true, but I use cameras that are 50+ years old, so I’m not replacing my technology every few years for thousands of dollars. I figure it all equals out in the end. And the best part: my negatives will live on, long after I’m gone.

You can find more of Smithson’s work and writing on her website and on Lenscratch.

About the author: Peter Levitan began life as a professional photographer in San Francisco. He moved into a global advertising and Internet start-up career. Peter photographs people around the world using a portable studio. This is his excuse to travel and meet people.

Image credits: All photographs courtesy Aline Smithson