Landscape Photography: The Frustration and Pleasure of Traveling Into the Unknown

![]()

“Landscape photography has actually been maxed out for years.” That’s what the former equipment manager of our local photo club told me around 1990. He was a lover of the infamous Cokin “tobacco gradient filter.”

I would never have dared to dream where my attitude would lead me many years later.

Background

In September 2019, I was about to embark on my third trip to Siberia. I again wanted to photograph in the Altai Mountains for my project “The Calligraphy of Nature“. Unfortunately, the time window available for this tour step by step shrank to about a week due to work-related necessities, which meant the trip was about to be canceled.

The carbon footprint of the flight alone was out of all proportion to the time available on location, not to mention the expenses. However, since the media coverage in Germany from and about Russia in this year was again very negative, I felt an immense desire to set straight these impressions — and what better way to do that than by visiting the country? This desire gave me the decisive impulse to dare to again take a look behind the Ural this year.

However, due to the little time available, the trip had to be rescheduled so that I would not have to spend too much time on the road. Instead of playing safe in the Altai Mountains with their fascinating and diverse mountain landscapes, I switched to the so-called “Altai Region” (Altai Krai).

I had touched on this area for the first time 2 years earlier — at that time completely unaware of what awaited me there. It is the eastern part of the West Siberian Depression, a region that is both unimaginably vast and unimaginably flat. The region is not very appealing for classic landscape photography unless you want to take a series of pictures that are repetitively characterized by an exactly straight horizon.

With a drone in my suitcase, things of course looked quite different. 2 years before I had then been able to take really interesting pictures of rivers meandering like crazy and, surprisingly, also very abstract pictures of sediments on the shore of the large salt lake “Kulunda”. For 2019, I had reversed my priorities: I wanted to photograph mainly the salt lakes that can be found in this landscape, and should I find interesting rivers, I would of course include them as well into my schedule.

You may legitimately ask how these motifs came about in my mind. The conditions were actually not that good:

1. I didn’t know anyone who had photographed here before and even less anyone who had taken aerial photographs here before.

2. I did not know any book or other publication on the subject.

3. In the end, I didn’t really know anything about this area. I only had the pictures from Google Maps. But these stimulated my imagination in a most intense way.

As indicated above, I always wanted to push boundaries in landscape photography. Discovering new landscapes and perspectives became an important part of my own creative process. A previously unknown area just screams at me: “Come!”, and the more barren this area may look at first glance, the more appealing the project seems to me, even if there is a greater risk of failure.

Fortunately, I’m completely free in my choice of subjects. The only thing I’m permanently lacking is time. Therefore I should try to use my little time available for traveling as effectively as possible, in the sense of maximum great output per day. But if I had to choose between a week for example in scenically undoubtedly magnificent Iceland (from where I’ve seen many uniform pictures of pretty much every waterfall and rock), or the same amount of time somewhere far off the beaten track, without even a hint of what pictures I’ll come back with after a week (possibly none at all?), I would always blindly choose the journey into the unknown. Ultimately, I choose the journey wherever my heart takes me.

Faraway in Russia, Searching for Subjects

I wanted to write about frustration and pleasures when traveling into the unknown because these two terms manifested themselves in a particularly intense way for me on the tour through the Altai Krai on two consecutive days.

We — that is my guide and interpreter, my driver, and myself — at that point had been on the road for a few days, and the yield of pictures was mixed. Long driving distances, bad roads, and the battery charging cycles of the drone set the daily routine.

For lack of alternatives, I simply planned my destinations using Google Maps. For this day we chose a really promising area: a cluster of salt lakes near the Kazakh border. On the image from Google Maps, these salt lakes seemed to have approximately round shapes and they also showed different shades of color — all in all very promising, and I had high expectations for the day. Another major point was the circumstance that the lakes seemed to be reasonably accessible — apparently, there were some kind of dirt roads leading there.

![]()

When my driver steered his small SUV away from the main road, first along sideroads and finally for what felt like hours along barely visible dirt roads into the lake area, an unpleasant surprise emerged. The first two lakes we visited had dried up totally. Over the wide plain and under thin clouds, the creamy light of late afternoon sat in incredible silence. I thought to myself: bad luck with these two lakes, now let’s bring up the drone. But from above, things looked even worse. Almost all the relevant lakes have been completely fallen dry, leaving flat, white, unpleasantly fishy-smelling lake bottoms.

What a debacle! A subject I really had been looking forward to seeing, simply wasn’t there at all. But who could have told me that these shallow salt lakes may dry out during summer? I didn’t know a single person who even knew of the existence of these pools. I was depressed and angry about this failure. This day was supposed to be one of the highlights of this trip.

Of course, it was clear to me from the start that these motives were very speculative. The aerial and satellite images from remote regions are often misleading in terms of coloring and situation. I should have been aware of this risk.

I then recalled all the nice sayings about the positive sides of failure and quickly wiped them away. After all, a beautiful picture would be way better than failing in beauty. And as is so often the case, the loss of one thing opened up the view on something else.

Further to the northeast, there was another lake which, although not shimmering in all these colors, might have interesting shapes at its shorelines. So, as the sun slowly sank lower, we plunged further into this surreal, incredible lonely landscape.

At some point, we stopped in the sandy plain near the mentioned lake. The shore and the islands indeed showed bizarre shapes, so that I was able to empty my 5 battery packs with great pleasure. It was a small consolation on this otherwise depressing day, and yet only a small foretaste of the next.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

We spent the night in a cute little holiday resort, which was already mostly deserted at this late point in the year. Considering the remote region, it was an almost exuberant luxurious accommodation.

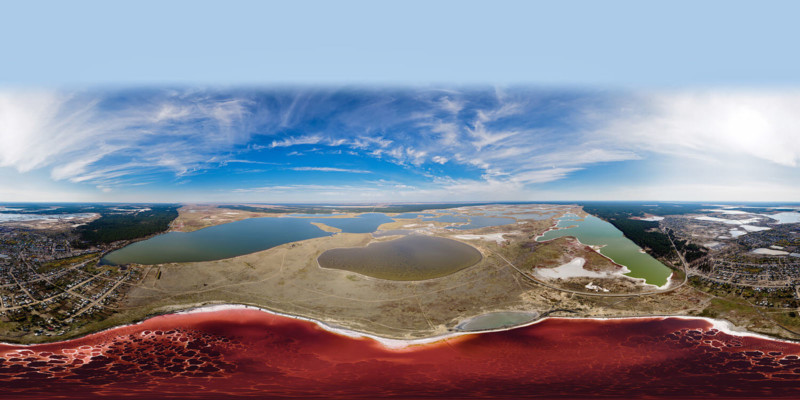

The next day we continued southeast towards “Malinovoye Osero” (Raspberry Lake) near the settlement of the same name. As the name suggests, this lake was supposed to be a very peculiarly colored body of water. The alkaline, bitter-salty lake contains “liver of sulfur water” in which brine shrimps and phytoplankton find good conditions for living. Depending on the season, the latter gives the water a pink or brown-red color.

After my expectations were not too high due to the pale pink satellite images, the experience of the previous day had made me even more pessimistic. In addition, there was a rumor that the large Raspberry Lake had largely lost its color. The salt concentration was supposed to have dropped due to an influx of a large amount of freshwater. In turn, this would have affected the living conditions of the phytoplankton massively.

As we drove from Mikhailovskoye through the lake area, it quickly became clear that the large Raspberry Lake had indeed lost its coloration. It was neither pink nor brown-red, but rather yellow-greenish in color. However, this time my fright lasted only for a short time, because near the village called “Raspberry Lake” we found another smaller lake which was already tempting us from distance with a promising color. We pulled off the road and I started the drone.

What I saw literally took my breath away. The lake was not of pale pink color but shimmered in unbelievably deep shades of red. And that wasn’t all: in the lake, crystalizing salts had formed almost hypnotic structures that seemed out of this world.

I spent the rest of my stay in this area alternately charging batteries and flying, charging, flying, charging. The settlement itself was not particularly attractive — my interpreter said that this was now my personal time travel to the Soviet Union. We had nice and clean accommodations in an empty private flat, but everything in the village seemed very desolate and incredibly far away from the rest of the world.

In this area, I had some wonderful copter flights — at the small Raspberry Lake, at different times of the day, and at the surrounding lakes. Behind the village was a chemical factory that had grown out of the “Mikhailov Soda Combine” founded in 1929, and which now produces under the name “Mikhailov Chemical Reagents Plant”. While I didn’t care much about the reagents, I was even more taken with the old soda salines behind the factory.

So there it was: the reward for all my efforts. Once again I had taken the long way around and, over all doubts and setbacks, had trusted my own intuition. In the end, I came back with pictures of a subject that I didn’t even know existed before.

I, therefore, reach the conclusion that trusting one’s own intuition is an irreplaceable cornerstone on the path to new motifs.

I should keep that in mind.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

If you want to look around the area: I have photographed a spherical panorama, which I hope you will enjoy viewing, rotating, and zooming into!

For all those who are technically interested, this is how the pano was created:

- First, I photographed all pictures “freehand” with the DJI Inspire 2 and the DJI Zenmuse X7 APS-C camera (focal length: 16mm equivalent to 24mm 35mm).

- The single images were converted from DNG raw files into TIFF files in Adobe Camera Raw.

- These TIFF files were merged into a spherical panorama using my preferred stitching-tool, PTGui.

- Afterwards I had to “patch” a small hole in the resulting file, because at one point I hadn’t paid attention and missed 100% coverage of the image tiles.

- Then I edited the whole panorama in Adobe Photoshop to my personal taste.

- Then I exported a large JPEG file. Afterwards, using the free software Marzipano, I created the files to be viewed in the Bowser.

About the author: Stephan Fürnrohr is a photographer born, raised, and living in Bavaria, Germany. The opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author. You can find more of Fürnrohr’s work on his website, Facebook, and Twitter. This article was also published here.