Uzbekistan Through The Lens of One of Its Only Street Photographers

![]()

Anzor Salidjanov conducted an experiment in 2009 that changed his life. In the poky gallery within the ancient city of Bukhara where he sold “monotonous” paintings of “minarets, donkeys, and camel trains” to tourists, Salidjanov decided to hang a couple of his photographs.

Soon after that first sale, Salidjanov rented a small studio where he could make money from shooting passport photos and continued pounding the streets of his beloved hometown with his camera, hunting for the elusive moments when light and life combine to create photographic magic.

![]()

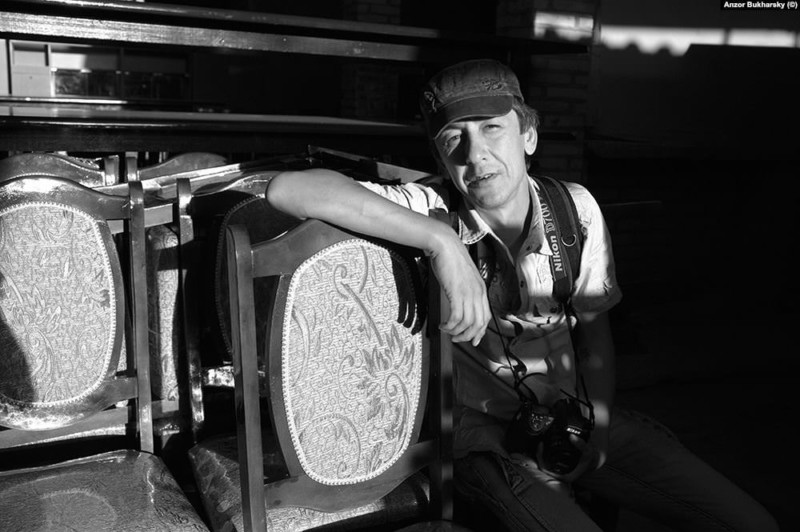

To complete his professional transition to photographer, Salidjanov adopted the emir-like pseudonym Anzor Bukharsky (Anzor of Bukhara).

But becoming a photographer in Uzbekistan was far from easy.

Bukharsky explained why there are so few good photographs made of his country’s culture and public life, especially from before 2016 when the country was ruled by the authoritarian former communist, Islam Karimov.

“Photographers were simply afraid to shoot on the street. Any policeman could easily detain the shooter and haul him off to the police station. I’ve had dozens of cases when I had to write explanatory notes for why I shot photos in a square or a market. Then the pictures themselves were deleted after being carefully studied for signs of espionage.”

“At the moment, I am constantly shooting on two cameras — Leica M9 and Leica M240,” the 52-year-old photographer says. “I also have a completely pocket-sized toy camera, which I carry in my purse — Leica C. It is a little more than a matchbox, and sometimes funny cards are obtained on it.

“But for some serious orders, I take my workhorse with me — Nikon D3x. This is a serious camera, and arouses respect among its customers, because in Uzbekistan, size has always been of paramount importance.”

Bukharsky says he is not interested in the tropes of photojournalism where conflict is sought out “between outsiders and society, individuals against the state, etc.” Instead of conflict, Bukharsky says, “I’m looking for harmony. The harmony of light, shadow, color, lines, and events.”

Sergey Ponomarev, a New York Times contributing photographer and multiple World Press Photo award winner, is one of thousands who follow Bukharsky’s work. He told RFE/RL: “I see [Bukharsky] as a real character. I enjoy reading his texts from time to time. I don’t know many Uzbek photographers from Bukhara and this makes him more outstanding.”

In 2009, Bukharsky became the first Uzbek photographer invited to exhibit at the Venice Biennale arts festival. He has since been invited to several photography events around the world. But traveling in and out of Uzbekistan as an artist is rarely a smooth ride.

As Bukharsky was returning to Uzbekistan from Latvia in 2015, he says an Uzbek border guard pulled an external hard drive out of his backpack, asking, “What’s in here? Porn?”

Bukharsky says: “I explained to the customs officer, ‘Now it’s not necessary to carry such material around. Everything can be streamed online.’” The officer was unmoved and took the hard drive full of Bukharsky’s photos away for an investigation.

For Bukharsky, who does not speak English, travel troubles don’t end at the border.

He described being woken up in the middle of the night in a Miami hotel room in 2017 with a woman banging on his door screaming what sounded like, “Open up, you bastard! I know you’re in there!”

“I looked at the phone on the nightstand and wondered how can I explain to the police that I need help? I don’t know English,” he recalled. Bukharsky said he made a plan to dial 911 and then “name the hotel and my room number and scream ‘SOS!’”

The scene eventually ended with the door thumper rousing a neighboring guest and disappearing inside.

The photographer says Bukharans “love their minaret,” and he is no exception.

“Sometimes my visiting friends raise their eyebrows in surprise, saying: ‘It seems we were here yesterday!’ To which I reply: ‘I am in my apartment every day. But that doesn’t stop me from returning there again and again.'”

Bukharsky has been photographing Romany communities in Uzbekistan for the past decade and says: “I am a welcome guest in almost any [Romany] home, glory be to Allah.”

Bukharsky, who is a single father with two girls, said that one of his Romany friends suggested he marry a relative of his, explaining that “you can sit at home or go out and take photos. Your wife will always feed you.”

Bukharsky says capturing an honest photographic record of Uzbekistan through the political paranoia and societal changes over the past decade was “a small miracle.”

But he dreams bigger. Much bigger.

In 2017, Bukharsky told an Uzbek journalist that he envisions for his future “a new apartment with a large 6-meter balcony that faces the setting sun (‘I’ve already looked at it. I’m bargaining now,’ he says.) Lots of travel, exhibitions, presentations, books, world fame, money — in bags. Fans pick up my red Lamborghini with me inside and carry it in their arms. And let a big friendly Uzbek family with numerous children and powerful relatives live in my old apartment and live happily.”

At the time of this writing, Bukharsky says he has indeed purchased the sun-drenched apartment, but the red Lamborghini is still a ways off.

About the author: Amos Chapple is a New Zealand born, Europe-based photographer and writer whose work has been published in most of the world’s major news titles. You can find more of his work on his website, Facebook, and Instagram. This article was also published at RFE/RL.