The Pros and Cons of Syndicating Your Photos

![]()

For a while now, I’ve wanted to cover the topic of syndication as it was a major factor in my work gaining widespread exposure and for the full-time career that I have now as a fine art, commercial, and editorial photographer.

I sometimes speak with photography students at art colleges (and more frequently get e-mails with questions from students of photography) and a common ask has to do with strategies about making one’s work stand out in an extremely crowded market. It’s always a difficult and complicated answer: beyond warning people to avoid gimmicks, it’s to focus on an area of photography that they love and to approach a subject of your work for the long game.

Usually I get the sense that students are eager to make a living in the field of photography and they want some kind of insight into how to replicate my success. But as an “accidental visual artist” who studied English in college, I’m limited in my capacity to advise them as I feel in most respects that this is a career that found me. But I do always advocate for the benefits of a broad, liberal arts education in helping one to know how to respond to doors of opportunity as they open (even though it means that I tend to not get asked back to speak by schools that are more than happy to have students majoring in Photography as undergrads).

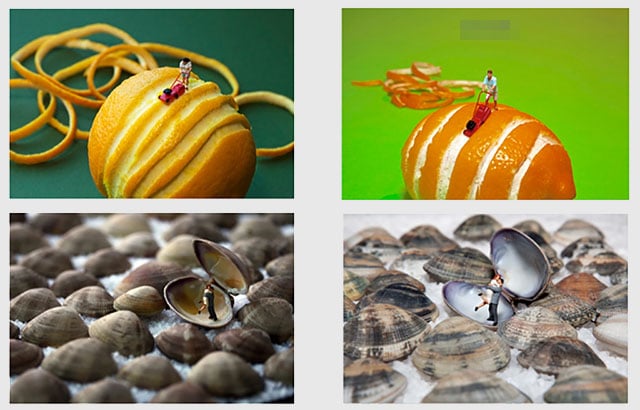

My Big Appetites photographs (which I first called ‘Disparity’) were something that I had been doing for almost nine years by the time they were first published. To be honest, I really needed a lot of that time too as I was an intuitive, self-taught photographer, more accustomed to shooting for journalism, travel, and portraiture. It took me a while to understand how to light for macro food photography and thereby run the roadblocks of my own shortcomings as a photographer.

These images with tiny figures were a tiny percentage of my total creative output. The key was really that I just didn’t give up on the idea. I kept pecking away at it whenever an idea came to me, from the time I made initial test images in December 2002 to the spring of 2011 when everything changed dramatically. Like many other photographers, I put my work online in those early days. But other than one of my young nieces who enjoyed the images, no one really cared or took notice.

I can’t recall now all of the places I had my images online. I’m sure I must have published some on various websites, blogs and iWeb accounts I had over time. I do know that I had images up on a photography website called Zooomr back in the day (a site I enjoyed a lot and that introduced me to the impressive work of Thomas Hawk) and later on Flickr (which I liked a lot less and that also contributed to my work being misappropriated). Making images available online was just the easy part. One still has the challenge of making them stand out on those sites where they exist among many millions of other photographs of pets, insects, flowers, hot air balloons, people’s kids, etc.

What catalyzed widespread notoriety for my work was a website called 500px based in Toronto. From the start, I perceived that the site seemed to be better curated by the other photographers putting their work there (fewer people were using it as a repository for pictures of their pets and family photos).

What I particularly enjoyed about 500px was that, since the site had been founded by Russians, it seemed to have a better balance of photographers from Russia and Europe opposed to mainly North Americans. So there was a discernible cultural difference that had a bearing on the look of the images.

Of course, like many other photography sites, there was a social aspect to it that would aid in building a following through a system of comments and ratings from peers. Though I don’t know that I’m all that talented in doing whatever I have to do to organically build a robust following. There are plenty of photographers who are very good at playing that game and understanding how it all works.

For me, it was just about putting up my best images, taking care to edit myself as best I could, and then being humble and grateful when people would comment or rate my work. I would also not be shy about commenting on and admiring those who I thought were doing work that inspired me. Beyond that, I really had no agenda about scheming to get my work “out there” or to market myself in a way that would bring me income.

I don’t recall how long I had been on the 500px site when (maybe around April 2011) I received a direct message out of the blue from an editor in Europe who pitched me the idea of syndicating my images. Knowing nothing at all about syndication I thought it might be a scam and my knee jerk reaction was to have reservations about sending twelve high-resolution images to a complete stranger on the other side of the world. But after some thought and discussion with my best friend, I decided to give it a shot.

What I learned is that worldwide media is hungry for interesting content for their publications. So syndicators will buy a group of images, will package it with a story, and will offer it to a range of publications. Once the content is in their system they will offer it to a network of syndication partners in other countries who will do the same.

![]()

![]()

The syndication agency I started with was Caters News, which placed my images in a handful of publications in the United Kingdom in May 2011. Although it wasn’t the first time my images had been in print, syndication was a completely new experience in many respects. I expected that I’d get a little bit of money. What actually happened is that my images quickly spread.

After appearing in England they were in Scotland. Then in France, Greece, and Italy. Then Pakistan and Australia. The photographs of tiny figures and food that I had worked on in obscurity for almost a decade were suddenly everywhere online. My inbox was flooded with comments and e-mails asking where people could buy prints. There were interview requests from editors and requests to use images that went on for months. I was even contacted by a book agent at a top agency, suggesting that the work would make a great book.

And there were galleries reaching out to ask if I would be interested in selling my photographs as fine art prints. Interest was suddenly raining down from the sky and I was running around with a paper cup trying to do my best to catch it.

That summer the work took off like a rocket, completely exceeding my expectations. What came first was just the attention. No one was writing me checks overnight. The money would come long after the notoriety. Big Appetites would go on to be published as a book but not until two years later. And I did start signing with fine art galleries. But that had its own process too.

For the purposes of the subject at hand, I think it is best to focus the rest of this post on the pros and cons of syndicating your images. We’ll start with the positive.

Pros

Broad exposure

Syndication is a powerful way to introduce your photography to the world. I can obviously speak only from my own experience and results may vary. But on the whole, syndicating my images got my work into a range of publications around the world, expanded knowledge of my photography very quickly and broadly, and brought me opportunities that I may not have been able to realize through other means. Doing two or three syndication deals, one after the other, for six months to a year at a time, resulted in my photographs being published in around 100 countries without me having to do much of the work in getting them there.

A little bit of money

Depending on the details of the syndication arrangements, the syndicator generally will split the profit with the photographer. So if the publication offers $250 for the content, you get $125. Some publications pay less, some more.

Awareness leading to opportunities

Many people have used the term “going viral” in reference to the way my Big Appetites photographs ricocheted around the Internet. And at a certain point, the notoriety did seem to have an organic power of its own. Though to be fair, much of the momentum had to do with the significant work that I did to keep it going. This involved finding a design house to put together a website for me, posting on social media, working very hard to continue the photo series by shooting a lot of new images, doing endless interviews via both e-mail and telephone.

I’d say the first six months or so were the most intense. Due to the widespread interest in my photography from around the world, I was often working on behalf of Big Appetites from very early in the morning to late at night. It is one thing to have doors of opportunity open. It is another to be prepared in a way that helps you figure out the best way to go through that door.

Cons

Lack of transparency

I found that syndication networks were less than clear about where my work was being used. Nor did they readily identify the other syndication networks they partner with. So while they would generate intermittent reports about where images were published, sometimes it was evident — like on the NBC Today Show website or InTouch magazine — and other times it would be some obscure Belgian print publication I had never heard of and that was identified in the payment report merely by way of an incomprehensible acronym. Which leads us to….

Copyright infringement

Certainly it is no surprise to any visual artist who uses the internet to promote their work that it is easy for others to take and republish images without permission. So as my photographs spread through the syndication networks, they just as quickly began to pop up on many (many!) websites of publications that had absolutely no right to use them.

I could write volumes about my experiences with copyright infringement. I’m not talking here about teenagers who discovered some of my images, found them funny and entertaining, and decided to post some of them to social media. I’m referring to mainstream news publications, which generate revenue from subscriptions, newsstand sales, and advertising, who just helped themselves to my work and used it as free content to enrich themselves.

The percentage of this activity probably comprised better than 40% of where my images went online. In some cases, it could be curtailed or stopped. But in many other cases (Turkey, Russia, Brazil, China, Argentina, just to name a few) the publications rampantly steal content with impunity.

I’ve frequently seen comments from amateur photographers who seem to like to assign me the blame for the image theft I’ve had to endure simply because I didn’t watermark my work before putting it online. The truth is that you can’t so readily sell your work with big, ugly watermarks on them. You most certainly can’t do that if, say, The New York Times or Washington Post is hiring you to create an editorial commission.

My experience has demonstrated that the world is full of entitled people with no respect for artist rights and they are more than happy to take your work and use it to gain attention/interest/traffic. This is not just news publications either, but commercial brands who take and use images without permission as they engage with customers on social media. But I digress. There is much to say about copyright at another time. I’ll just finish by saying that the lack of transparency and clear accounting from the syndicators makes copyright enforcement tricky.

Slow payment

Having done editorial commissions I can tell you that print publications are not well known for paying contributors quickly. Working through syndication networks as no exception. Do not undertake syndication arrangements if you are expecting to collect payment swiftly or to generate a living wage. If you are patient, however, and view this income as part of an overall plan as a working photographer, then you’ll be fine.

Unexpected uses

Read your syndication contracts carefully to avoid getting yourself in a situation in which your images are being offered in a way that you’re not comfortable with. For example, you might be thrilled to see your pictures used in a large feature spread in a major magazine or newspaper. But you might not be OK with your images being offered to stock agencies as well, especially when you couldn’t potentially make a lot more by directly licensing your work on your own (to audiences who might be outside of the contract, like commercial entities).

Exclusivity

I think I worked with three different syndication agencies over a period of a couple years, but none simultaneously of course, as contracts require exclusivity. In my experience they ask you to commit for a certain amount of time, I’d say at least six months. So be sure you are OK with sticking it out. Business generally works better when professionals abide by their contracts.

It’s a volume business

Certain publications seem extremely hungry for syndicated content. I’ve had my work featured in major newspapers in the UK only to have them see my work somewhere else six months later and come back to me to ask if I’d like to be featured in their publication. They have so many different photo editors and churn through so much content that it’s likely they don’t remember that they’ve already published my work. I do take care to offer them fresh content and new text (if they’re looking for it). And here is but one reason this is on the list of cons:

There was the time a copycat amateur photographer in Italy replicated the exact same composition of about a dozen of my images and managed to sell a feature story to a UK daily newspaper. As if that weren’t creepy enough, he even went so far as to do an entire interview about the work, pretending that the idea was his, and sourcing most of the answers about his inspiration from the text on my own website. I only learned about the feature when the fine art gallery in London that was representing my work altered me to it.

The paper immediately removed the story when I brought it to their attention and, likely understanding their liability in the matter, offered to pay me. I declined their payment, accepting their apology and the removal. The point was made. It did drive home how eager they are to fill column inches, not to mention how so many unethical photographers out there will happily bask in the attention and accolades for their “creativity” and “originality” when they’ve totally cribbed the idea from someone else.

Sometimes it is hard to turn off

I generally had positive experiences syndicating my images through Caters News and Rex Features.

Syndication arrangements with Barcroft Media were initially positive during the time I did business with them but were later severely tarnished in a significant breach of trust when, more than a year after our arrangements had expired, my photographs we discovered as still being offered for sale through one of their syndication partners. They apologized, saying they did everything they could to inform their syndication partners that they were no longer authorized to offer my work for sale. They claimed that it was a simple mistake.

I accepted their adamant assurances that it would never happen again and then moved on, only to discover four years later that yet another of their syndication partners still had my images available for licensing. I was less willing to overlook this as a mistake and saw it for the gross negligence and infringement of my copyrights that it was.

This should be an instructive lesson in the way that a lack of transparency on the part of a syndication company may result in your images still being offered or sold for years after the contract ends, simply because you have no way of knowing yourself which partner companies might still have your images as the main syndication company won’t reveal it to you.

In summary, syndication can be a powerful way to gain notoriety for your work. Though it comes with some serious drawbacks that can temper the benefits. Overall, the exposure of my work through international syndication was the kindling on which I built the fire that is a full-time career in fine art, editorial, and commercial photography that is keeping my hearth warm to this day.

About the author: Christopher Boffoli is a fine art, commercial and editorial photographer based in Seattle, Washington. The opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author. Boffoli is best known for his Big Appetites work, which features tiny figures posed against real food landscapes. In addition to his commercial and advertising work for brands large and small, his fine art photographs may be found in galleries and private collections in the United States, Canada, Europe, and Asia. You can find more of Boffoli’s work on Instagram. This article was also published here.