How I Shot the Tesla Roadster in Space from 1 Million Miles Away

![]()

Whatever your spin is on the SpaceX launch of the Falcon Heavy and the stunt of Starman and the Tesla Roadster, for a few days (at least) it put on our radar topics such as space and space missions, rockets, interplanetary travel or technological advances.

I spent a big part of February 8 trying to find the Roadster’s ephemeris, that is, a list indicating the coordinates of the spacecraft over time. Luckily, NASA’s Jet Propulsion Lab, which produces ephemerides for thousands of celestial objects, had just added the roadster (designated 2018-017A) to their list.

I quickly generated the ephemeris for the Tesla and mapped them on TheSky6, the software application that I use to control my telescope. I didn’t receive good news, as the Roadster appeared to be cruising through an area in the Hydra constellation that would put Starman barely 20 degrees above my horizon at most this time of the year. This meant that I would need to photograph it through a much denser layer of atmosphere, which affects these kinds of observations.

The only times the Falcon Heavy would be high enough above the horizon were between 3 am and 5:30 am, while it’s still dark. The ephemeris from the JPL also indicated that the Roadster’s brightness would be at magnitude 17.5, so I knew that my goal was perfectly achievable.

I didn’t wait any longer. Without getting any sleep, at 2 am (already February 9) I headed to a semi-dark site not far from home (I live in Sunnyvale, California) for which I have a night permit — Montebello OSP. I rarely ever come to this place to do astrophotography because its proximity to the San Francisco Bay Area causes it to have only mildly dark skies. Still, I was tired, it was late, and I didn’t have the time or energy to start a 2+ hour drive for much darker skies. I knew 17.5 is a magnitude I could achieve from Montebello, and the quick 40 minutes drive from home sounded just about right.

Let me give you a brief description of my gear, what I use for most of my deep-sky images. I have a dual telescope system: two identical telescopes and cameras in parallel, shooting simultaneously at the very same area of the sky — the same FOV, save a few pixels. The telescopes are the Takahashi FSQ106EDX. Their aperture is 106mm (about 4″) and they give you a native 530mm focal length at f/5.

The cameras are SBIG STL11k monochrome CCD cameras, one of the most legendary full-frame CCD cameras for astronomy (not the best one today, mind you, but still pretty decent). All this gear sits on a Takahashi EM-400 mount, the beast that will move it at hair-thin precision during the long exposures. I brought the temperature of the CCD sensors to -20C degrees (-4F) using the CCD’s internal cooling system.

Once I had my rig all ready to roll, I pointed my dual telescope setup to the area where the Roadster was supposed to be and focused. I use electronic RoboFocus focusers that I control with the program FocusMax, so perfect focus is achieved automatically, no sweat. I then calibrated the autoguider, that is, a third smaller telescope whose sole purpose is to find a star in the FOV and keep tab of its movement at subpixel accuracy — whenever it detects that the star moved, it instruct the mount to move so as to always keep the star at the same place. Autoguiding provides a much better mount movement than tracking, which is leaving it up to the mount to blindly “follow” the sky. By actually “following” a star, we can make sure there’ll be no trails whether our exposures are 2 minutes or 30 minutes long.

It was time to take the first shot. The moon was already rising. At 30% it wasn’t too bright but it definitely washed out the already not-too-dark skies. Still, I knew a mag 17.5 object would be detectable, so that didn’t detract me.

Considering the Roadster’s trajectory over two hours wasn’t going to be any longer than 3-4 minutes (arc distance, not time), my FOV of 3.5×2.2 degrees was huge — even if the coordinates were a bit off I knew the little guy would be in it somewhere. I set my gear to take 2-minute exposures of Luminance with one scope, while the other would be capturing color data with R, G, and B filters.

Come the first shot, I quickly go check it out while my rig keeps taking the next shots. All astronomical images are extremely dark, and some histogram adjustments are needed in order for us to see anything, so with the usual stretching tools I adjust the image to give me a good visual of the field.

Nothing.

Not just a doubtful thought ” maybe it’s there but I didn’t capture”, no. There was absolutely nothing there. I wait for the second shot to finish. Nothing. Third, fourth… Now I’m looking for differences between the shots since the Roadster would be the only thing significantly different. Nothing.

I didn’t just call it a night. I’m in the field, it’s almost 4 am, it’s cold and I’m tired, so I give myself the benefit of the doubt that I may just be missing it and that I’d be able to spot it at home with my large monitors and better tools, so I leave my rig taking shots continually, one every two minutes, plus about one minute gap to download the image from the CCD to my laptop (yes, it’s shamefully slow but still, these CCDs weren’t built for timelapses).

By 5:15 am, I felt it was enough. Twilight was coming soon, plus I wanted to avoid the rush hour traffic back home, so I packed and left.

After a few hours of sleep, I started playing with the data. But no matter what I did, I could not find the Roadster. I kept checking the coordinates — nothing made sense. So I decided to try again. The only difference would be that this time the Moon would rise around 3:30 am, so I could try star imaging at 2:30 am and get one hour of Moon-free skies. Maybe that would help.

So by 1:30 am (this is already February 10), I’m at the same place again. Set the gear, rinse and repeat, I started imaging sharp at 2:30 am. Except that within half an hour, high clouds started to appear and my hopes vanished. I stayed a bit longer, but by 4 am things weren’t improving, I counted my losses, packed and headed home.

After a quick nap, I go back to all my shots but find nothing, still puzzled about the whole thing.

Then it hit me!

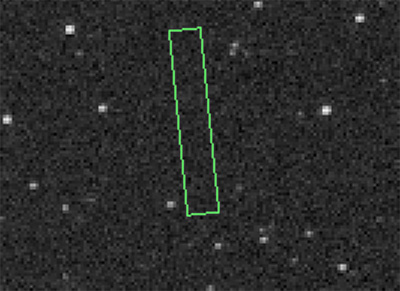

When I created the ephemeris from the JPL’s website, I did not enter my coordinates! I went with the default, whatever that might be! Since the Roadster is still fairly close to us, parallax is significant, meaning, different locations on Earth will see Starman at slightly different coordinates. I quickly recalculate, get the new coordinates, go to my images, and, thanks to the wide field captured by my telescopes, boom! There it was! Impossible to miss!

It had been right there all along, I just never noticed!

The rest was easy. First, I calibrated (apply flats and darks) and pre-processed all shots with PixInsight. This includes registering (aligning) all 32 shots, removing gradients, obtaining proper color balance, doing some moderate noise reduction and histogram adjustments. With that done, I then brought all shots into Photoshop for final adjustments, adding the text overlays and building the actual movie.

Astrophotography can be applied in many different ways. I utilize technology that allows me to capture ancient photons so that I can later process and create my own interpretation of the data captured, effectively blending art and science like not many other disciplines do, but I don’t usually track “small pixels in space” (aka comets, asteroids and yes, even spacecraft) as some of my peers do.

Yet, surely enough, there came a day when someone decided to launch a cool red car “driven” by a dummy in an astronaut costume, so I had to go for it! Yeah, red sports cars make even tiny pixels look cool.

About the author: Rogelio Bernal Andreo (aka RBA) is an award winner astrophotographer living in California. In 2007, he started exploring astrophotography as a hobby and developed a personal style defined by deep wide field images that led to international recognition and a meaningful influence on the discipline. To see more of his work, visit his website or follow him on Instagram and Facebook. This post was also published here.