A Brief History of the Camera Flash, From Explosive Powder to LED Lights

![]()

The first known photograph was captured in 1826 when light reacted with a particular type of asphalt known as Bitumen of Judea. Since that first natural light photo, photographers have introduced artificial flash lighting to photos through all kinds of different ways. In this post, we’re taking a look at a brief history of the camera flash — from its humble beginnings with explosive powder and burning metal up through the latest LED lights — to see how far it has come.

Flash Powder

If you have watched any movies depicting life in the nineteenth century, you may have witnessed a photographer holding a tray that suddenly produces a bright flash and a loud bang. In some slapstick comedies, a cloud of smoke might then dissipate showing the photographer standing with a blackened face. This technique utilized what we now call flash powder.

![]()

Flash powder is a composition of metallic fuel and an oxidizer such as chlorate. When the mixture is ignited, it burns extremely quickly producing a bright flash that can be captured on film. Before being used for photography, flash powder was commonly used in theatrical productions and within fireworks — a practice we continue to this very day.

Needing to ignite flash powder by hand was an extremely dangerous endeavor that could seriously injure the photographer and those in close proximity. As a result, a safer solution had to be devised that could ignite while reducing the chance one’s face might get burned. A bit of improved safety came from the flash-lamp that was designed in 1899.

Flash Lamps

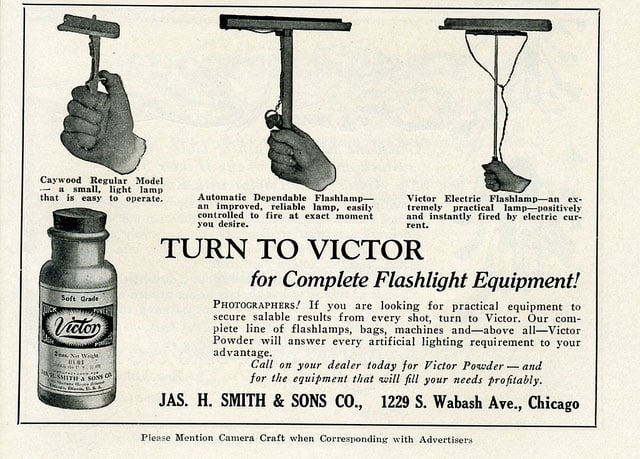

Joshua Lionel Cowen, an inventor best known for his Lionel model railroads and toy trains, and photographer Paul Boyer introduced the flash lamp right before the turn of the twentieth century. The design had a trough that would hold flash powder to then be ignited via electricity from a dry cell battery.

The flash lamp was typically connected to the shutter of camera boxes, allowing for the flash to be activated as the photographer snapped the photograph. The flash mechanism could be placed on a tripod away from the camera for activation. One could also connect multiple flash lamps to be ignited at the same time when in a series.

An alternative solution, developed by Bunsen and Roscoe, was to ignite a magnesium ribbon that reproduce a light temperature similar to daylight while burning. Photographers would cut the strip of metal dependent on the duration of their exposure then ignite it to illuminate their subjects. Despite Bunsen and Roscoe’s idea being around first, flash powder was more widely adopted by photographers looking for a bit of artificial light.

While the flash lamp was able to make the practice of flash photography a bit safer, it was still very dangerous when compared to today’s standards. Photographers were still injured in the practice and, in some cases, died while attempting to prepare the powder for usage. Luckily, a new solution was just around the corner.

Flash Bulbs

In 1927, the first flash bulbs were produced by General Electric (some argue that they were initially made by the Vacublitz company in Germany). Instead of lighting magnesium powder in the open air, flash bulbs were closed lamps that contained a magnesium filament along with oxygen gas. Initial bulbs were designed out of glass, but they were later switched to plastic when it was discovered that the magnesium’s ignition could break the bulb.

Of course, flash bulbs were far from the perfect solution: the bulbs tended to be incredibly fragile and could only be used once. Also, the bulbs were typically too hot to handle after they were fired. Manufacturers did eventually replace the magnesium with brighter burning zirconium for a more powerful flash.

Some interesting quirks of flash bulbs include the fact that the time needed to reach full brightness and the maximum duration of the flash were both longer than the electronic flash units of today. As a result, cameras with flash synchronization capabilities typically fired the flash bulb before opening the shutter to expose the film.

![]()

Flashcubes And Flipflash

As you might expect, constantly replacing flashes can become a bit annoying for the average photographer. As a result, Kodak introduced the Flashcube in the late 1960s. The flashcube contained four different flashbulbs for usage. Simply snap a photograph then rotate the cube to use the next flashbulb. Manufacturers quickly took note of this idea and began creating their own compact solutions.

![]()

The first non-Kodak solution was the General Electric Flipflash, which arranged eight to ten flashbulbs in two rows. A photographer could plug in the cartridge, fire four to five shots, then flip the unit over to access the other four to five bulbs. Other companies including Phillips, Polaroid, and Sylvania also released their own versions of the Flipflash while carefully navigating around General Electric’s product patents.

Electronic Flash

What the industry needed, however, was a flash that wouldn’t die after being fired once. Back in 1931, Electrical Engineering professor Harold Egerton began work on the first electronic flash tube. It took a good amount of improvement and decreased costs for the devices to finally become popular in the second half of the twentieth century.

![]()

Electronic flashes would come to use a capacitor to store power for later use. When an electronic flash is triggered, the capacitor releases its energy through a flashtube, which is filled with gas that produces an intensely bright light for a very short time. Excellent synchronization, along with the ability to change intensity on the fly, made electronic flashes the dominant solution while pushing flashbulbs into obsolescence.

![]()

Today, we use electronic flashes within studios and on-the-go to illuminate our subjects and scenes. Tubes within electronic flashes are typically filled with xenon gasses and have a relatively long lifespan before needing to be replaced with an entirely new unit.

With the advent of wireless technology, multiple flashes can also be placed off camera and synchronized without the necessity of a complicated setup. We also now have high-speed flashes that can discharge light in extremely short amounts of time.

LED Flashes

Unless you are carrying around a Nokia Lumia 1020, then your smartphone most likely does not contain a xenon flash. Current smartphones use LED flashes as a source of light when photographing in low light conditions.

![]()

LEDs are nowhere near as powerful as xenon flashes, but they are a lower voltage and minuscule — perfect for the pocket. Some companies (i.e. Apple and Nokia) have integrated dual color LED flashes into smartphones to help produce more natural skin tones.

And there you have it: a brief history of the camera flash, from early its origins until now!

Image credits: Header illustration based on photo by Dan Eckert, flash powder photo by Conejo de