Interview with Photographer Dave Jordano About ‘Detroit: Unbroken Down’

Dave Jordano is an award-winning documentary photographer based in Chicago, IL. Jordano has exhibited widely and his work is in several private, corporate and museum collections, most notably The Museum of Contemporary Photography, Chicago, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, and the Detroit Institute of Arts.

He published his first book titled “Articles of Faith” in April 2009 by The Center for American Places, Columbia College Press. His current project, Detroit: Unbroken Down, documents the cultural and societal identity of his hometown, Detroit.

![]()

PetaPixel: First off Dave, talk about your early experiences with photography, and what prompted you to make it your profession?

Dave Jordano: My introduction to photography was somewhat of an epiphany. While stationed in Nuremberg, Germany as a soldier in the Army in 1968, I was invited by a friend of mine who had a camera with a few extra frames on his roll of film to take portraits of each other and then go to the local photo lab on the base to develop the film and make some B&W prints to send back to our parents. Feeling bored with nothing to do that Saturday morning I agreed.

When I entered the darkroom to develop the film, it immediately hit me that this is what I wanted to do for the rest of my life. I had never felt anything as strongly as I did that morning. In many ways (and no pun intended) it was like a light went on in my head, and for the first time I knew this would be my life’s path. I suppose it’s about as close to a religious experience as you can get.

Fortunately for me, the woman who ran the photo lab became an important mentor to me. Her name was Frau Nastvogel, an elderly retired woman who used to run a portrait studio in Nuremberg. She looked at my first contact print sheet and declared, “Oh, you must become a photographer!” I remember her being even more excited than I was, like she had made some great discovery.

She was a wonderful teacher, but more importantly it was her aesthetic sensibility and approach to making meaningful pictures that guided me through that first year. I wrote my older brother a letter to tell him of my newfound interest and how much I loved photography, whereupon he sent me a book of Cartier-Bresson’s work, which blew me away. His work was magical and inspired me to look at the world differently.

PP: Who are your biggest influences, photographically or otherwise?

DJ: Well, Frau Nastvogel of course would be one! She never stopped believing in my potential, even though I was just a kid of 19 at the time.

Another important influence was one of my teachers, Bill Rauhauser, who taught at the College for Creative Studies in Detroit in the early 70’s. Bill was an early pioneer of street photography and his knowledge of history and photo theory was immense. His critiques were invaluable to me. Now 95, he was recently awarded the prestigious 2014 Kresge Eminent Artist prize for his contribution to the medium and his teaching.

I also became aware of works by Ansel Adams, Minor White, and Paul Caponigro. I aligned my visual aesthetic more with them than with Cartier-Bresson, so within a year I bought a 4 X 5 view camera from a local camera shop in Nuremberg. This was still a period of experimentation for me, but I was really drawn to the slow, contemplative, methodical, precise way of working with a view camera. I guess you could say that it fit my personality.

I was basically self-taught during my military stint, so all I had to go by were books I could find in bookstores. Other photographers I discovered at the time were Happy Callahan, Edward Weston, Alfred Stieglitz, Walker Evans, and Eugene Atget.

PP: Since 2010, you’ve been working on a project called Detroit: Unbroken Down. Please give us an overview of why you began this project.

DJ: It all started when I saw work by other photographers who had visited Detroit and were documenting all of the abandonment and empty factories there. The terminology most frequently used today to describe this genre of work has been coined “ruin porn.”

Initially, I went back to do a re-photography project by take pictures of the same locations that I documented 35 years earlier to see how the city had changed over time. My intent was to simply to go there for a week or two, finish the project, and put a portfolio together of the work. I hadn’t been back to Detroit in over three decades when I moved to Chicago in 1977 to start a career as a commercial photographer, so my first reaction after my first visit back was utter disbelief!

I couldn’t believe the level of destruction that had taken place. This certainly wasn’t the Detroit I remembered as a young man going to college in the early 70’s. It looked more like a city from a third world country. This fascination by other photographers and the media to only see Detroit from this narrow, one-sided point of view affected me deeply. It became imperative that I needed to figure out a way to flip the script so to speak, to try and right what I thought was a horrible misrepresentation of a city that had fallen on hard times.

PP: What are the underlying issues that caused Detroit to become the city it is today?

DJ: You can’t really pinpoint one particular event that brought Detroit to its current situation. Several factors all working simultaneously created a scenario of failure that made its economic collapse inevitable.

The race riots of 1967, which accelerated the white exodus to the suburbs, financial institutions that redlined neighborhoods based on color which plummeted real estate values and eroded the tax base, labor disputes and the right-to-work law which depleted manufacturing and assembly jobs away by the thousands, a lack of economic diversity, city mismanagement and rampant corruption, and blind corporate arrogance towards foreign auto competition all led up to Detroit’s bankruptcy.

Ironically, Detroit’s own phenomenal success of making automobiles also contributed to its downfall, facilitating an easy escape for suburban expansion and the ability for one’s desire to own a home on a larger, greener patch of grass.

PP: This series offers a humanizing take on the economic and social issues surrounding Detroit. Why did you decide to photograph the city in this way, as opposed to showing the dilapidating surfaces of its architecture and infrastructure?

DJ: My first attempts to photograph Detroit were like everyone else’s. I too was mesmerized by all of the empty, crumbling factories and the forty square miles of abandoned homes that littered the city, but it only took me a week of shooting this kind of subject matter to make me realize I was contributing nothing to a story that everyone already knew much about.

I also didn’t feel comfortable working this way either. It felt as if I had turned my back on the city and joined the ranks of all those who rallied to capitalize on its failure. Clearly, if I were going to do anything meaningful at all, it would have to be about the people who still lived there, so I chose to concentrate on the neighborhoods and those who lived within them.

My work is really not about what has been destroyed, but more importantly about those who have been left behind and how they’re coping with the spoils of a post-industrial city.

PP: As a collective portrait of the city and its residents. Talk about those you met and photographed. What are their overall feelings towards the city they live in?

DJ: What I find so satisfying about the people of Detroit is their attitude. I’ve made over 23 trips there over the past three years and almost all of the people I’ve met display an uncanny ability to remain positive.

There’s no question that this is a reaction to all the bad press they’ve had to endure, but beyond that their resiliency and determination to survive is matched only by their sense of pride. The people of Detroit are proud of their history and where they’re from and there is definitely something about living in Detroit that propels them to transcend all the hardship and negativity associated with it.

In many ways, people there have been living with so little for so long with their backs against the wall that it has actually crafted many self-sufficient communities. Bartering is a common practice, community gardens are an essential part of the food chain, neighborhood watches are in effect and many residents pitch in to clean up the abandoned lots on their street.

This collective effort is something you don’t see in more affluent neighborhoods but is born out of a necessity in poorer areas of Detroit. When city services become so lean, residents will often take it upon themselves to improve their surroundings. There are two ways to look at your situation, you either accept it or you try to improve it. This, to me, is encouraging on a human, social, and personal level.

PP: Discuss some of the decisions that went into your shooting. How did you meet those you photographed, and how did you decide just where in the city to make your images.

DJ: Detroit is massive in scale, totaling 140 square miles. You can place all of Manhattan, Boston, and San Francisco within its borders! It’s also not an easy city to learn your way around because there is no north-south, east-west grid system like Chicago. It’s more like a series of various quadrants colliding with each other at different angles, often making it difficult to keep a sense of where you are. I really had to learn the city all over again, often using up an entire tank of gas in one day just driving around. Sounds silly I know, but this was my modus operandi.

Encounters with strangers were always part of a game of chance and luck. I wasn’t shy about getting out of my car and introducing myself if I saw someone or something that was interesting to me. Often a long conversation would ensue until finally I would mention I was a photographer doing an independent documentary on Detroit.

Most would comment on all the emptiness there was to photograph, but I would tell them that I wasn’t interested in that and that I was doing a personal project about the people who lived there. I almost always received a positive reaction, mostly because they were impressed that someone like myself, a stranger, actually took an interest in them.

I make no excuses about searching out the poorest neighborhoods in the city to work in, but this is where I would always find people who possessed a high level of hope and a persevering spirit. I’m not what you would call a photojournalist per se, but someone who melds the principles of fine art, portraiture, and documentary photography together.

PP: Is there a specific feeling or idea that you’d like your viewers to walk away with?

DJ: Of course. All photographers have a point of view and mine embraced the idea of revealing a more human kind of connection to the city. It was important to me that this work be viewed as a testament to the perseverance of those who have continually struggled to get by and that there is still life in Detroit. It’s not all just about emptiness and abandonment.

I made the work on my own terms, expressing my own thoughts and feelings about a city that I felt connected with. If others feel the same way as I do then I guess I’ve succeeded in making some allies.

PP: With all the unique characters that appear throughout this work, who among them stand out to you?

DJ: You know, I’ve met so many people that it would be impossible to single out anyone in particular. The fact that so many have let me into their lives and allowed me to photograph them really speaks to the openness and generosity of their acceptance of me.

There were a myriad of different people that I encountered, and all of them had figured out in some way of overcoming the obstacles and difficulties in their lives. This is the central theme to the work, that Detroit is still a living, breathing city, struggling perhaps, but full of people surviving.

One caveat to this work are the portraits that I’ve made of street prostitutes. Their lives are crippled by drug addiction, but their open and ubiquitous presence on the streets of Detroit in broad daylight speaks volumes about a city that is broke, exhausted, short-staffed, and unable to deal financially with a serious, chronic social problem. I see these women more as helpless victims, having to sell their bodies to support their drug habit, as opposed to being criminals. The irony is that many of them look to be just normal women, perhaps a close friend or relative.

PP: Do you have any stories you can share from your experiences in Detroit? This project seems like one that would offer many adventures…

DJ: Well, as I said there are so many people who deserve mentioning, but I have met and become very good friends with one man named Tom.

He was homeless for a long time and tired of living on the street, so about ten years ago he found a patch of land on an abandoned railroad line along the Detroit River. He built what was essentially a doghouse out of materials he would scavenge from construction site dumpsters. He lived for seven years in his little house without running water, heat, or electricity, heating the space with candles in the winter.

When I first met Tom a few years ago, he was in the process of building a second house that was twice the size of his first one. He didn’t have anything to protect his roof so one day I went and bought three flats of shingles and anonymously dropped them off. The next time I visited him they were perfectly installed on the roof. He’s a very skilled carpenter and built the entire house with nothing more than a hammer, tape measure, pencil, and a rip saw, again building it with discarded materials he found. The point is he overcame a negative situation by taking positive action. He’s since rebuilt his first house with better insulation so that on extremely cold nights he has somewhere warmer to stay.

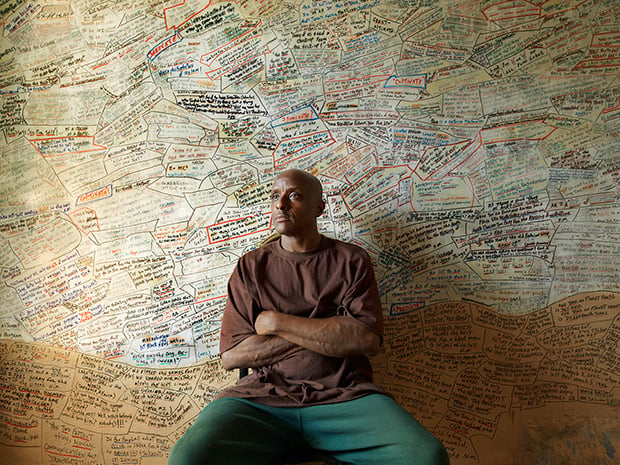

Another man I’ve become good friends is Hakeem. Broke, divorced, and after losing his business, he found solace and strength through his Muslim faith. He scraped up $500 to purchase a run down house on the north side of town and now repairs cars from an abandoned two-car garage across the alley from his house. Turning a small room of his house into a place for meditation and reflection, he continually writes original phrases of wisdom, inspirational quotes, and factual tidbits on his walls that guide his moral and spiritual life.

Always positive of mind, he doesn’t see himself as a victim anymore, but someone who accepts adversity as a metaphor to building ones character. I see this kind of makeshift ingenuity being used in so many ways in Detroit. It has become synonymous to the culture there.

A writer for the Detroit News saw my portrait of him on my website and emailed me asking where he lived. He then did a nice story on him for the newspaper’s blog. The day after the story ran, Hakeem was inundated with phone calls (his phone number was painted on the outside of his garage in one of the pictures the paper ran) from people who wanted to help him out by giving him money, tools, food, and even free health insurance.

PP: Were there any neighborhoods you steered away from that might have seemed too dangerous to wander through?

DJ: No, never. I’ve met hundreds of people in Detroit, many who live in the roughest neighborhoods of the city and not one of them ever treated me badly or made me feel threatened. The perception that Detroit is a dangerous place and that all the people who live there are criminals is the biggest fallacy that I can think of. It just isn’t like that.

Just because you’re poor doesn’t make you a bad person. All cities have crime and Detroit is no exception, but the vast majority of people there are good, honest folk who are no different than you or I. Having said that, I wouldn’t be naive enough to think that I couldn’t wind up in the wrong place at the wrong time. It’s a risk, but one that I have been willing to take.

PP: Is this project finished or are there plans to continue it indefinitely?

DJ: That remains to be seen. I certainly have enough material to publish a book and have exhibitions, but my underlying motivation to continue working there is still strong. In many ways I feel like I’ve only tapped into the surface of what’s possible. Besides, I’m never really satisfied with what I’ve produced, so I guess that’s one of the reasons that drives me to keep going back.

I’m having a solo show of my Detroit work this February at the United Photo Industries Gallery in Brooklyn that runs through the middle of March.

PP: Thank you for your time Dave.