William Henry Fox Talbot: Inventor of the Negative-Positive Photo Process

![]()

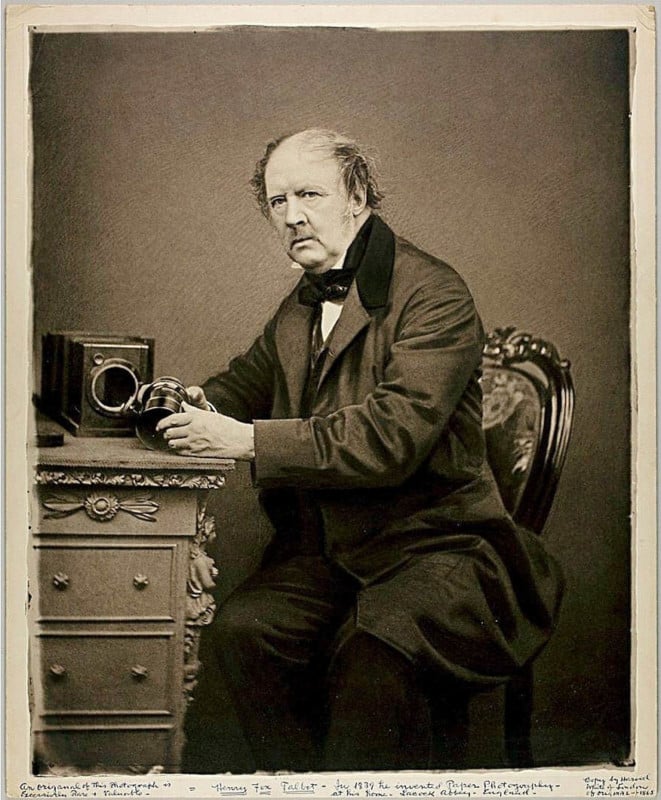

William Henry Fox Talbot was on his honeymoon at Lake Como in northern Italy in 1833. He was trying to sketch the beautiful lake and the surrounding scenery but was becoming increasingly frustrated with his lack of drawing skills. He used a camera lucida and a camera obscura, two devices that use lenses to project an image onto a piece of paper to aid in drawing, but he didn’t find either one very satisfactory.

![]()

How charming it would be if it were possible to cause these natural images to imprint themselves durable and remain fixed upon the paper! And why should it not be possible? I asked myself. —William Henry Fox Talbot

In this quote, Fox Talbot is saying basically, “I wish these scenes would draw themselves.” And why not? With this, he set out on a project to try to fix the fleeting image to paper. It was known that certain chemicals change color or get darker when exposed to light. The challenge was to stop them from changing and thus become permanent images.

Fox Talbot was the man for the job. He was a scientist, mathematician, botanist, etymologist, and Member of Parliament. He was well educated, had plenty of resources, and was well connected with the English elite. He was also humble and not at all a self-promoter. For that reason, much of his contributions to photography, publishing, and scientific discoveries are not often appreciated nor particularly well documented.

The First Photographs

Upon his return to his home at Lacock Abbey in southwestern England near the city of Bath, Fox Talbot began experimenting with coating paper with silver nitrates and silver chlorides noting how they changed when exposed to light. He was not alone in this experimentation.

In France, Nicephore Niepce, Louis Daguerre, and Hippolyte Bayard were performing similar experiments. In the U.S. Samuel Morse, the inventor of the telegraph had experimented with silver nitrate as early as 1810. Others in England including Sir Humphry Davy and Thomas Wedgwood also conducted similar experiments. In all cases, the challenge was not in getting an image to appear on paper, but to stop it from getting darker and turning black.

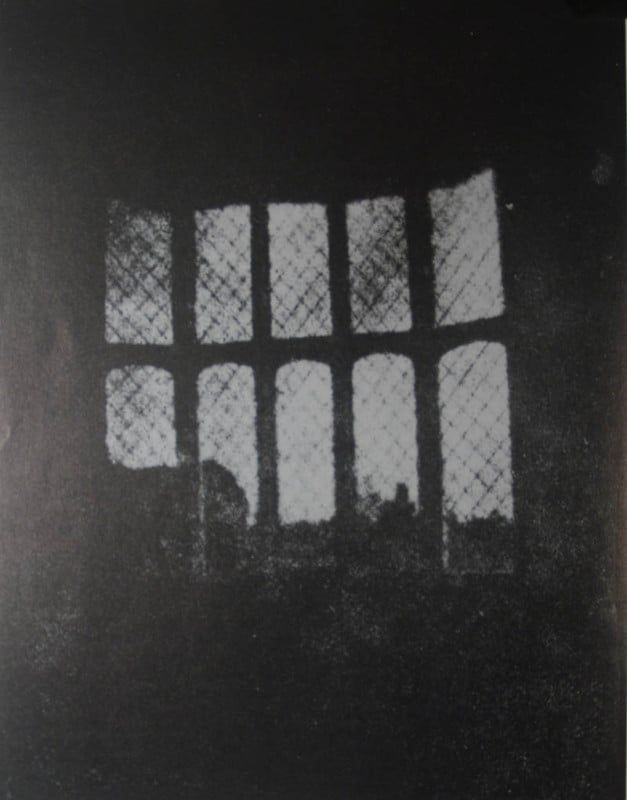

By the fall of 1834, Fox Talbot was having considerable success in fixing the image and was sending paper prints to friends. Some were images of items laid on the sensitized paper, but he soon began using little wooden boxes with a lens to capture natural scenes. His wife called them “Mousetraps,” partially because they looked like mousetraps, but also because he sat them around various places to capture the light and make images.

One of the first true photographs was of the window at Lacock Abbey.

Here is the current external view of the window at Lacock Abbey:

![]()

The Negative-Positive Process

The images were negatives, so they had to be contact printed onto another piece of paper to make a positive image. Consequently, they were quite soft and fuzzy. He eventually figured out how to soak the paper negative in an oily solution to make them more transparent to give a sharper, more distinct image.

It was first thought that this two-step process was a disadvantage, but he soon realized that this negative to positive process allowed for multiple copies of the same image to be made. This negative-to-positive process would become the most common process for making photographs for the next 160 years.

Daguerreotype

Meanwhile, in France, Louis Daguerre was working on a similar idea but with a totally different process. In Daguerre’s process, a sheet of copper is coated with a thin layer of silver, highly polished, and then sensitized with iodine and bromine vapors. After being exposed in a camera, the metal sheets were processed with heated mercury fumes.

When he presented his photographs at the joint meeting of the French Academy of Scientists in August of 1839, the world was stunned and amazed. Daguerreotype studios immediately began to spring up as Daguerre sold cameras, supplies, and lessons, to the new professional photographers. The French government gave Daguerre a lifetime pension in exchange for making the patent public property.

The mood in England was quite different. Scientific inventions were generally left up to the moneyed class who could afford to work on their own without financial assistance. Furthermore, patents were generally frowned upon and considered to be greedy attempts to make money from ideas that should belong to everyone. For that reason, Fox Talbot was generally ignored by the English government and his contributions were seldom acknowledged at the time.

Further Development

Daguerre’s announcement spurred Fox Talbot to get back to work. Even though Daguerre’s images were sharp and clear, each image was unique with no way to make multiple copies.

In 1841 Fox Talbot patented his negative/positive process as the “Calotype.” He was then able to sell licenses in England, France, and America, sometimes marketed as Talbotype. Ultimately, however, Talbot’s efforts to maintain patent control over the negative/positive process failed, despite lengthy court proceedings. Over time, the merits of the negative/positive process and being able to print on paper became more obvious; Talbot’s processes became increasingly more important over the years.

Fox Talbot also began hand-tinting the paper prints to make color photographs, invented the half-tone process for printing, and published the first book illustrated with photographs, The Pencil of Nature.

Who was First?

Who actually made the first photograph is still open to dispute. We can assume that the French believe it was Daguerre and the English chose to believe that it was Fox Talbot. The Fox Talbot Museum at Lacock Abbey and the Niepce Museum at Niepce’s home in the commune of Saint-Loup-de-Varennes, France both proudly proclaim that they are the home of the first photograph.

The first photograph could have just as easily been attributed to Morse or several others, but most people would agree that the direct line to modern photography and the processes up to today’s digital imaging runs from William Henry Fox Talbot. He was the first to coat paper and make a duplicable permanent image on a paper that can be reproduced in unlimited quantities.

For further reading, a great book on the life and impact of William Henry Fox Talbot, and a resource used for this article, is Fox Talbot and the Invention of Photography by Gail Buckland.

Image credits: All modern photographs by Jim Mathis