Spencer Tunick: Photographer of Mass Nude Photos

![]()

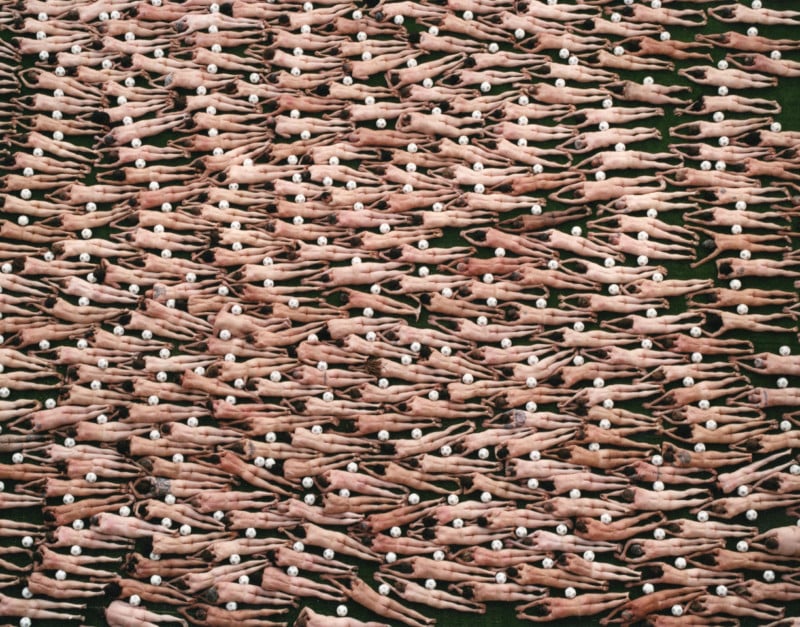

Photographer Spencer Tunick has captured groups of nudes in close to 100 public spaces all over the world. His largest masterpiece was a group of 18,000 people who took off their clothes in Mexico City’s Zocalo Square, the heart of the ancient Aztec empire.

Tunick started in the early 1990s with individuals and small groups. In 1994 he organized a group photo with 28 people in front of the United Nations in New York City, transforming his work – from just photography to installation and performance.

Warning: The photos and videos in this article contain nudity and may not be safe for work.

Posing unclothed people en masse metamorphoses them into a new shape in Tunick’s art. The artist seems to be examining the separation of identity and privacy in his illustrations, which often have identifiable backgrounds – from a Swiss glacier (imagine posing naked at 50°F) to a canal in Amsterdam to a football stadium in Vienna, Austria.

Tunick has said that other artists may use oil or clay to shape their subjects. He does the same with nude bodies to create his abstractions. His canvas is the setting he chooses, whether rural, urban, indoors or out.

Promoting Early Skin Cancer Detection at Bondi Beach, Australia

On November 26, 2022, Tunick assembled 2,500 Australians on Bondi Beach a little before the sun came out for his latest installation. This is the number of Australians who die each year from skin cancer.

“The skin cancer charity, Skin Check Champions (@skincheckchampions), contacted me out of the blue,” Tunick, the New-York-based photographer-artist, tells PetaPixel. “I had scouted Bondi Beach in 2009 in Sydney, Australia, but I chose the Sydney Opera House [for photographing a previous installation]. So, I was familiar with what was possible and not possible logistically and artistically.

“Many of my works have meaning behind them, but I don’t include the meanings in the titles of the works. In the 90s, for my group works, I did title the works with the meaning of the work, but as time went by, I used the location as the title. Often the later works have two titles—one that I reveal and one that I don’t actively put out there.

“I shot from a lift for the first set-up, 16 meters [53 feet] high. And then, for the second set-up, I moved to a cliff much higher. Fujifilm Australia kindly loaned me two lenses for this set-up, the Fujifilm GF 120mm f/4 R LM OIS WR and Fujifilm GF 250mm f/4 R LM OIS WR. I ended up just using the 120mm for that set-up.”

Bondi Beach does not allow nudity, but they changed the local legislation to permit nudity, and the designated area was declared a nude beach until 10 am on the photography day. Tunick started assembling the participants by 5.30 am (sunrise was 5.38 am) and finished by 7 am.

The Photography Workflow

Tunick generally needs a high vantage point to capture the huge installation of people he has assembled.

“When I am not on a lift, I am most often on a ladder,” the artist explains. “And my assistant is right next to me on an identical ladder. So, we are working 4 to 5 meters [13-16 feet] up.

Tunick is not a trigger-happy photographer and captures images conservatively.

“200-300 [frames per session],” he figures. “I treat medium format digital the same way that I shoot film. I try to shoot the same amount as I did with film. I don’t like to have too many options to choose from. But I do need to shoot more frames. My assistant has to remind me to keep shooting.”

The photographer usually has a megaphone as he is often far away from the participants, and in the open, there is a lot of ambient noise that he must speak over.

“I travel with a small crew on the ground with walkie-talkies helping me to arrange the people,” he says. “I use a megaphone or sound system and both at times. My crew of around five and many volunteers helps arrange the people [into the shape that I need].

Most of the participants are performing for the first time. However, two Delta flight attendants, one male and one female travel to “do my works.”

The commissioning organization or art institution normally gives the participants a print in exchange for posing.

“So, everyone gets a print,” says the artist-photographer. “I wish I could pay. If I paid one person, I would have to pay everyone. If I paid people, I would not financially be able to make the work. So, it’s an exchange. This is the way I have been doing it since I started. I just photograph too many people.”

Tunick says that the participants usually keep their clothes close by and out of the camera frame, so it does not need any elaborate check-out procedure.

Beyond the technicalities, the most crucial thing for Tunick is to remain calm no matter what happens.

“To remember to focus, technically and mentally,” says Tunick. “To hold the camera tight. Before each installation, I write “Calm-Focus-Tight’ with a sharpie on my hand to remember to do all these things, and it sets a mental tone for the day ahead.”

So, does he remain calm even when the local police arrest him for code violations in New York City, his favorite place to capture installations? You bet he does.

“It’s actually legal to be nude for art in New York City, so even though I was arrested, I was acting within my legal rights to make the work,” claims the New York-based photographer. “The mayor at the time, Rudy Giuliani, did not like the law. So instead of trying to change it, he instructed the city not to give me permits. And for the police to arrest the participants and me.”

The Largest Installation had 18,000 Participants

When a photographer talks of capturing a large group, the number is usually 50 or 100 or maybe 200 people, but for Tunick, that is a small installation.

“[We had] 18,000+ people in the Zocolo Square in Mexico City,” says Tunick. “Approximately 40,000 people registered to participate, and in the early morning, half showed up. As the sun was starting to rise, I had to stop the inflow of participants because I was shooting into the sun, and at a certain point, the flare from the sun would make the work unusable.

“I’m so thankful to all the participants who made it and those who didn’t make it into the square. And really, I am truly grateful for everyone who participates in these works. I could not do this without the participants and volunteers… and I don’t mean that abstractly, I couldn’t do it. I mean, I literally could not do it! Afterward, there was a handout where the people who took part and the volunteers received a photograph from that morning in exchange for their participation.”

Yikes, that must be some job for the assistants to print 18,000 photos instantly!

Film vs. Digital

“When I used to shoot film, I would need to wait to start until the sun allowed me to,” recalls Tunick. “Which was handheld using a Mamiya 7 II when I reached f/4.0 at 60th using 800 ISO film. My first frame could only be taken handheld 10 minutes before sunrise. But now, with the invention of IBIS, I can start much earlier and handhold.

“When Fujifilm discontinued 800 ISO color negative film, I was devastated. I did not like the Kodak 800, which was still available then. I tried the Kodak film but failed miserably.

“I purchased all the Fujifilm 800 still in New York from K&M Camera in NYC and labs around the country. I had 500 rolls.

“But then Fujifilm came out with the GFX medium format system, which had Image Stabilization (IBIS). That was a game changer as I could start shooting on a ladder handheld at a much earlier time in the morning when pedestrian and vehicular traffic was less.”

“[I used the] Pentax 6×7, [medium format film camera], and my favorite lens was the 105mm f/2.4 working on a tripod between 1992-1998,” remembers the installation photographer. “But I decided to move on from that camera when I started to shoot handheld.

“In 1998, I moved to the Mamiya 7 II and the 80mm f/4.0 N lens because I could shoot handheld at a 60th. With the Pentax 6×7, if shooting handheld on a ladder, too many frames would be affected by shake and not come out sharp.

“[Currently, I use] the Fujifilm GFX 100 medium format. The Fujifilm GF 50mm f/3.5 R LM WR and Fujifilm GF 63mm f/2.8 R WR are my most frequently used lenses with this camera when working on my group series. I recently purchased the Fujifilm GF 80mm f/1.7 R WR for my individual portrait series.

“I really don’t have a favorite Fujifilm lens. If it were to exist, my dream Fujifilm lens would be a Fujifilm GF 63mm f/1.4 [Fujifilm, are you listening?].”

Tunick has no interest in tilt/shift lenses or very high-resolution camera backs of 150 megapixels.

“I don’t want too much clarity,” says the photographer. “I often shoot the GFX set to 800 ISO, as I like the digital grain that the files have. There is some magic sauce that Fujifilm uses where their digital grain very closely resembles film grain when the images are printed large scale.

“I don’t like the backgrounds of my works to be too much in focus. It’s maybe the opposite of Andreas Gursky and Candida Hofer’s style. I don’t want people to grasp the background completely.

“I want the people in the foreground to be the focus and in the back of the image, the people and the landscape to blend in a softer environment. So, if you’re standing in front of the actual 48×60 inch print, you would be able to see that the work is not about obtaining the maximum depth.”

Adobe Lightroom is his editing software after downloading the RAW (always) files.

“Lightroom, but it is difficult for me to learn it fully,” he laments. “I would need to go back in time, not have children and be back in school, to have the time to learn it. But I have wonderful assistants and friends that help me with Lightroom. I guess I need to wait till my kids are in college to find the time to learn it.

“I will edit the images the day after an installation in the hotel with my assistant, make the final image choices, and work on the images with them in Lightroom. Then I will back up to two SanDisk SSD G-Drives- identical backups. I take the drives home in two separate carry-on bags. I take a bag, and my project director takes the other as we head back on a plane to New York.

“The largest I used to print was 71×90 inches on C-print paper, but now I print on pigment paper, and the largest I can print is based on paper size availability. The paper I use currently only goes up to 60 inches wide. So, the largest I can print is 59×75 inches, with 1/2 an inch border around it for safety.

Tunick relies on his camera’s autofocus, shooting RAW in single shot mode and not with continuous on motor drive. And there is no exposure bracketing or focus bracketing.

Chance Meeting Provides the Creative Catalyst

“One of my first works came about when I was sitting outside eating on St. Marks Street in New York City in the spring of 1992, and an amazing-looking person walked by on the street,” Tunick remembers the 30-year-old incident as though it happened yesterday. “We made eye contact, and he walked on by. I ran after him and stopped him. Before I even said a word or asked him anything, he said, ‘Yes.’ I think he took from my enthusiasm that something creative would happen with our meeting.

“To my surprise, it was a former Alvin Ailey dancer Alistair Butler and one of Robert Mapplethorpe’s past subjects. A big, small world NY was back in the 90s. I made many works with Alistair until he sadly passed away from AIDS a short time later.

“When I brought him his prints at the St. Vincent Medical Center in Greenwich Village, his health was in decline. He was in the medical bed and could barely speak. He could talk a little and told me that I had turned him into an angel. Knowing that my photographs made this impression on him at the end of his life had such an impactful effect on me. I miss Alistair.”

Getting Started in Photography

“My father owned the photo concessions at some of the hotels in the Catskill mountains in upstate NY,” remembers Tunick. “I would photograph hundreds of hotel guests with a half-frame camera [during high school days] and then sell their photos in small plastic keychain viewers the following day.

“I spent a lot of time in the International Center of Photography library when I was in their Creative Practices program in 1989-90. I was fascinated by artists using photography to document their art performances.

“And often, the photographs that enamored me were not taken by the artist creating the performances but by a hired photographer or friend of the artist. I fell in love with the documentation of the performances of Yayoi Kusama and Carolee Schneemann.

“After studying their work for some time at ICP, I took elements of Edward S. Curtis and Diane Arbus’ photographic techniques (not content) and found my vision.

“[My first film camera was the] Olympus Pen EE-3. It’s the first camera I ever used, and I still use it for my Scopes series and Artist Model series.

“I went right from medium format film to the medium format digital Fujifilm GFX system. I skipped full-frame digital cameras. I don’t like the 3:2 image ratio for my art. I only like the 5:4 ratio as you look through the lens, and when the GFX 100 came out, it had 5:4 and IBIS. So, for me, it was finally what I was looking for. But with that said, it is heavy, and I’m not a spring chicken anymore. So, we’ll see how long I can physically work with the camera. It would be fine if I were 35 or 45, but at 56, it’s a bit more difficult.”

“Most often, my works are commissioned by museums and art institutions,” explains Tunick. “There are times when my works are supported by commercial entities that support the museum’s commission of my work.

“Only recently, I have started to work with arts sponsorship directly from companies. But I would say that art institutions directly commission 90% of my work. With that said, I am not [emphasis Tunick’s] opposed to commercial work anymore. The right thing has not come along yet.

“I’m an exhibiting artist, so I survive off of the sale of my framed photographs resulting from the individual works and group installations. I also have an artist fee to execute the installations, pay my crew and keep up my studio.”

Tunick has plans to do a moonlit installation in the future, but the opportunity and the right project and location have not come up yet.

“I did photograph my wife nude with moonlight outdoors on our honeymoon in Tulum, Mexico, in 2002,” says Tunick. “It was a very long exposure.”

Tunick’s oeuvre is a unique kind of nude photography where everything is visible, and nothing is visible, involving patterns, colors, abstractions, and well-known places. It has fascinated the viewer for the last 30 years and will surely interest for the next 30, if not more.

You can see more of Spencer Tunick’s work on his website, Instagram, or in his books.

About the author: Phil Mistry is a photographer and teacher based in Atlanta, GA. He started one of the first digital camera classes in New York City at The International Center of Photography in the 90s. He was the director and teacher for Sony/Popular Photography magazine’s Digital Days Workshops. You can reach him here.

Image credits: Header photo: Desert Spirits 1, 2013 © Spencer Tunick and Tunick portrait at Bondi Beach. All photos courtesy of Spencer Tunick