Neil Montanus: The Photographer Who Shot the Most Kodak Coloramas

![]()

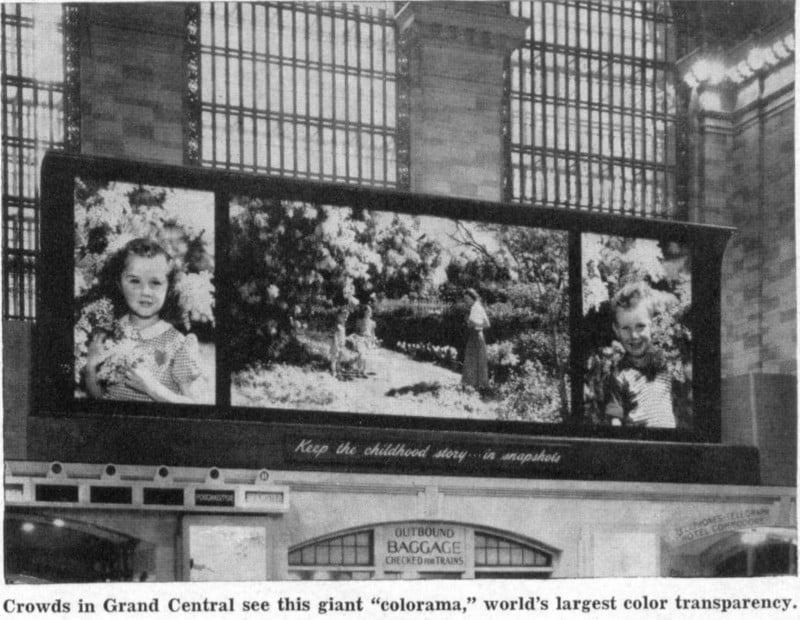

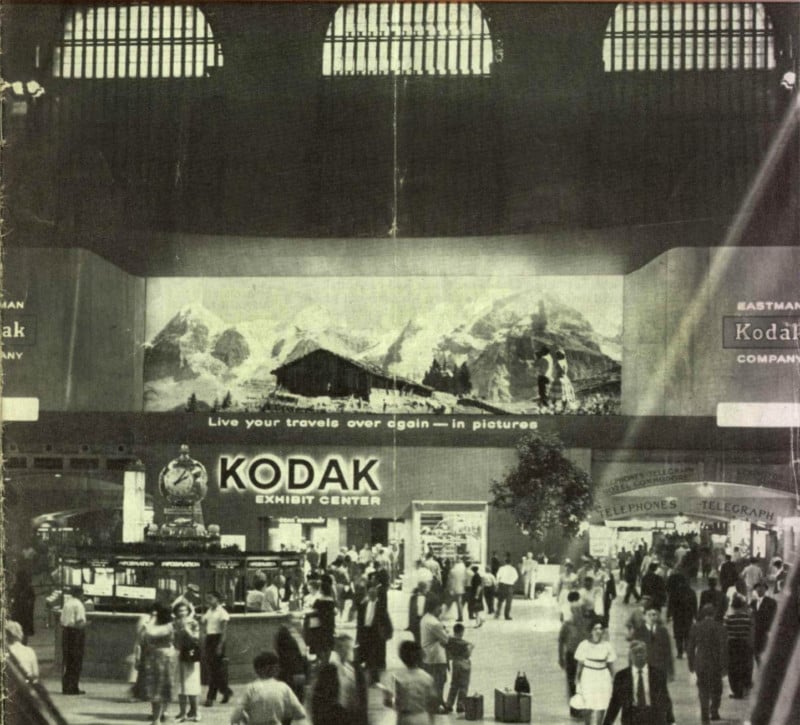

The Eastman Kodak Company displayed Coloramas – giant backlit photos 18 feet high and 60 feet long – at Grand Central Terminal in New York City for 40 years starting in the 1950s. The photographer who made 55 of them was Neil Montanus.

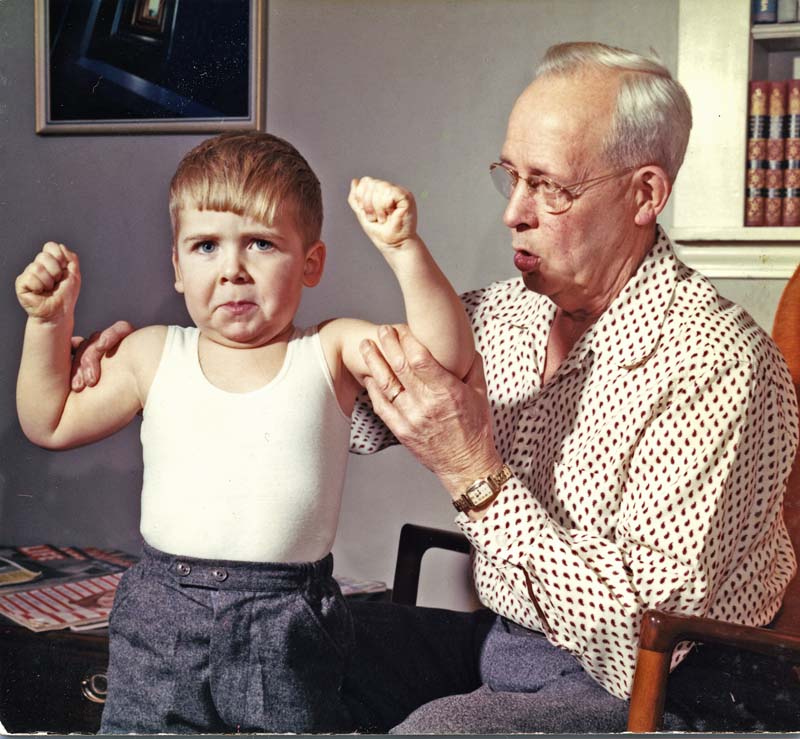

In all the early images, a photographer was prominently shown capturing the moment with a Kodak camera.

Coloramas, ‘The World’s Largest Photographs’

The word “Colorama” came from the 1939 New York World’s Fair where Kodak exhibited a curved screen so that you would not get distortion from the multiple projectors that actually made up the image and “rama” is kind of a curved structure. The Grand Central image was not curved but equally large, and the same name was used.

In the post-WW II Kodak ad campaigns created by the “mad men” at J. Walter Thompson, the emphasis was on showing amateur photographers that color film was as easy to use as B&W and the Coloramas were a continuation of the same push.

Coloramas, backlit by a mile of cold cathode tubing, showed images of American families driving, boating, playing with their children in their living rooms, at the pumpkin patch, dancing, or simply enjoying the good life. Kodak paid $93,000 rent per year in 1950, and this rose to 500,000 dollars in 1989.

In the four decades that the Colorama program ran, Kodak produced 565 images, and in the early part of the program, the photos were changed every few weeks to keep up the freshness and excitement for the viewers.

In May 1950, when the first Colorama was revealed, Edward Steichen, Director of the Department of Photography at New York’s Museum of Modern Art, telegraphed Kodak with these words: “EVERYONE IN GRAND CENTRAL AGOG AND SMILING. ALL JUST FEELING GOOD.”

The Most Prolific Colorama Photographer

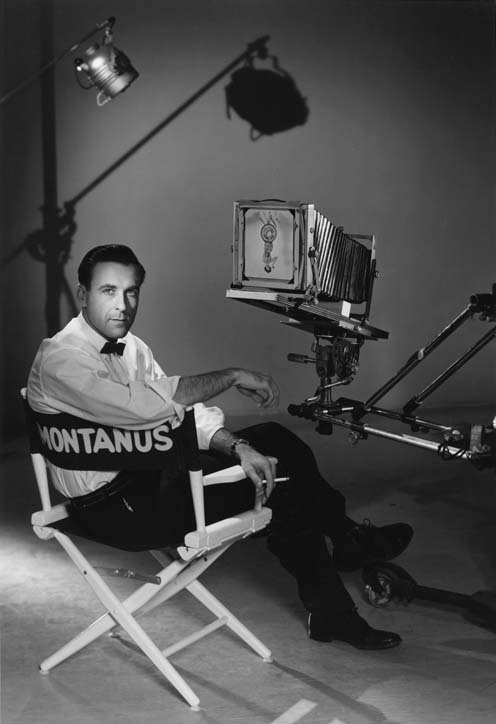

Neil Montanus, who passed away in 2019 at age 92, was the most prolific Coloramas photographer, having shot 55 of them.

“My dad was relentless with the camera, constantly taking pictures of us kids and everything else,” his son Jim Montanus, a pro photographer in Rochester, New York, tells PetaPixel. “So much so that it drove us nuts sometimes. But that was one of the secrets of his career: that his shutter rarely stopped clicking.

“And that included non-stop camera, film and technique testing. He never stopped learning, and according to his fellow photographers in the Kodak photo studios, he was endlessly curious, often visiting their studio sets wanting to see what they were up to and asking many questions.”

The first Colorama that Montanus captured was a couple boating in Vermont with the fall foliage behind and the water cascading over the pool’s edge onto rocks below.

Montanus drove around for a few days, searching for a suitable scene. When he found a lake that would work, he got a rowboat and painted it red. He got a local couple to model for him, and a picture-perfect composition for a Colorama was born on an 8×20-inch Deardorff camera using a very sturdy tripod.

The 8×20 Deardorff was a Banquet Camera designed with a narrow aspect ratio also made in 7×17″ or 12×20″ to ensure that all the guests seated at a banquet table were recognizable. As wide-angle lenses and smaller formats became popular, their use died out.

Banquet cameras were no longer used in the 1950s, but Kodak got Deardorff to custom make them for the Colorama project as they were a good match for the required aspect ratio of about 1:3.

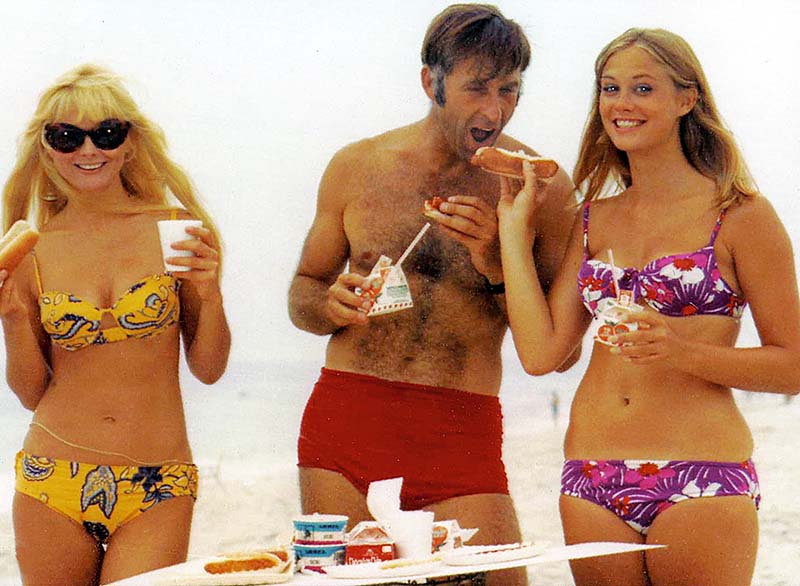

Other images Montanus produced were Teen Dance in the Basement, Autumn Scene in Lake Placid, Adirondack Mountains of New York, Discotheque, Family Springtime Scene – near Atlanta, Georgia, Richardson’s Canal House Inn, Bushnell’s Basin, New York, and many more stateside and also in international locations.

The First Underwater Colorama

Jim Montanus remembers his father telling him how he developed an underwater camera to be used for shooting a Colorama in 1977.

The photographer jerry-rigged an aerial camera with a large film load, 10″ wide. Unfortunately, it focused only at infinity, and he had to shim the lens to come forward to make it focus at 11 feet. This was a giant camera, and a custom-made monstrous underwater housing was created out of three-quarter-inch plexiglass.

The housing had too much air in it and kept floating to the surface, so it had to be weighed down with eight stainless steel rods.

“It was the story of how he and a friend pioneered underwater photography techniques to create the world’s first underwater Colorama,” says Jim Montanus. “They custom-built huge underwater housing for a vintage Fairchild K-17 WWII aerial reconnaissance camera and then modified the K-17 to shoot roll film without the electricity [by hand cranking] it would have had in a WWII bomber.”

From a Giant Banquet Camera to a ‘Tiny’ Nikon

The last Colorama Montanus shot was of a Cheetah in Kenya, Africa, in 1989. In those 30 odd intervening years, film emulsions had become much thinner and sharper, and it was possible to enlarge it to 60 feet even from a one-and-half-inch wide 35mm transparency.

The transition from a 25 lb. behemoth of a banquet camera in 1960 on an equally heavy tripod to a handholdable 35mm was incredible. Also, Montanus could quickly jump back in the truck when the cheetah “loped over to investigate.”

“300mm f/2.8 Nikkor, and at that time, it would have been a Nikon F4, I believe,” says Jim Montanus.”

The Cameras, Films, Lighting, and Printing of Coloramas

“Also, later in the program, Coloramas were taken with the Linhoff Technorama [panoramic images on 120 film] camera,” adds Jim Montanus. “A few were shot with a Hasselblad.

“The Coloramas were shot on formats starting with 8×20” to 35mm film. They were all [except for one] shot on color negative film. VPS 120, Vericolor type S. At least one was shot on 35mm Ektar film. One was shot on 35mm Kodachrome. Also, some used the center cropped section of an 8×10 VPS Negative.

“My Dad used early electronic strobes to do the shot [Christmas Carolers],” Jim says. “Ascor 800 flash units but used photofloods for focusing.

“The Coloramas were first printed on Ektacolor print film, then later on Duratrans print material. Depending on what year it was made, there were either 20 or 15 vertical strips [printed in sections and then glued/taped together] in each Colorama.”

On the sixth floor of a Kodak building (B28) was a swimming pool that was never filled with water, and here the Colorama transparencies were dried overnight. The pool bottom was also used to display and check the full transparency before being trucked out to Grand Central Terminal for the installation in the middle of the night. A small light panel was moved under the transparency to “proof” and see how the image would look when it was finally backlit.

“The print itself cost $30,000 to make,” Jim Montanus says. “The costs to shoot it varied wildly. One photographer shot one on his desk. While others traveled to far-flung places around the world.”

Neil Montanus’s Journey to Kodak

Montanus (1927- 2019) grew up in the tiny Midwestern town of Ashton, Illinois, during the depression. At age 10, he won a Chicago Tribune photo contest of a kitten inside the bell of a tuba. That image sealed his fate and career.

World War II was underway when Montanus turned 18, and he joined as a photographer and sharpshooter. He later attended the Rochester Institute of Technology on the G.I. Bill.

Montanus graduated from RIT in 1953 in portraiture and photo advertising illustrations. After graduation, he was hired as the manager of a large portrait studio near Chicago. A year later, Kodak hired him as a portrait specialist in 1954. A secondary job came from RIT, which asked Montanus to teach portraiture in an evening division.

Montanus ended up working at Kodak for 35 years. Soon after joining, he began to form his own unique style as opposed to the formulaic advertising shots of Kodak. He excelled and perfected photographing dance, nudes, fine art, portraiture, landscapes, and underwater photography, but his crowning glory was the Colorama project. His departmental boss knew that when Montanus proposed a shoot, he would always return with the photos.

The Colorama photographer was also a nude photography specialist and taught it for 30 years.

“He taught nude photography at the Kodak Camera Club in Rochester,” says his son. “Kodak was fine with that, with the caveat that he couldn’t do the photoshoots in the Kodak studios, so they had to be on location.”

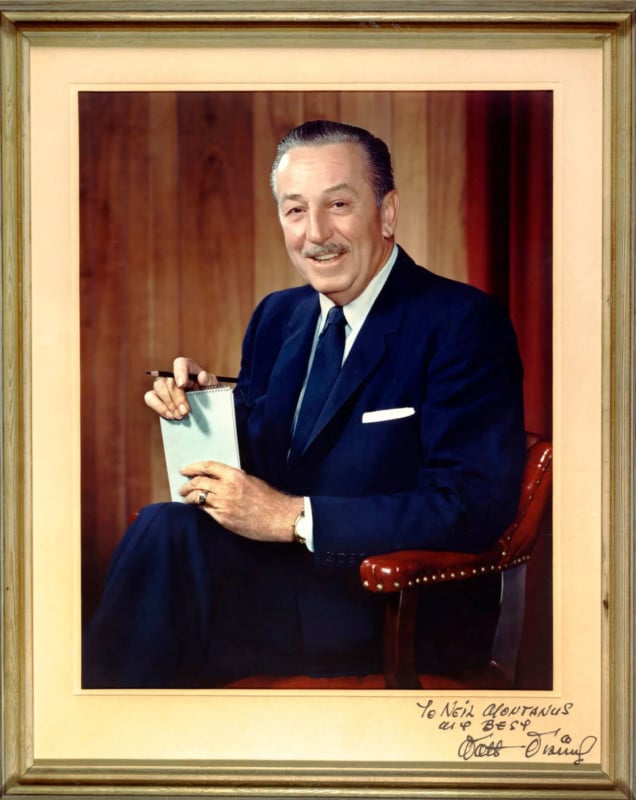

A Portrait of Walt Disney

“Walt Disney was my favorite,” said Montanus to the Democrat and Chronicle on March 31, 2017. “He was in Rochester because he came to Kodak to talk about sponsoring a show on TV. He and I got along beautifully.”

He came away with a professional portrait of Disney sitting in a chair while wearing a navy-blue suit and holding a pencil and a notepad.

Disney executives subsequently called Montanus’ portrait “the best portrait ever taken of Walt Disney,” and it is still in use at Disney facilities today.

Going Digital at Age 75

“Even though he was around 75 years old when digital began to become more mainstream, he loved the immediacy of digital — the ability to proof the work instantly and also the control it gave him over the editing process,” says Jim Montanus. “Especially coming from a world where he and other pro photographers used polaroid backs to proof their images back in the day – an expensive and tedious process.

“And editing large-format color images were done by someone else at Kodak. Digital gave him more creative control. And although he built a darkroom in his home after retiring from Kodak, he preferred the ‘digital darkroom.’

The Lost Coloramas

The archive is still physically located in the family home’s basement, which Jim’s son purchased from the estate. Jim Montanus is working on finding a permanent home for the archive but not until he has had a chance to go through and digitize many of the images.

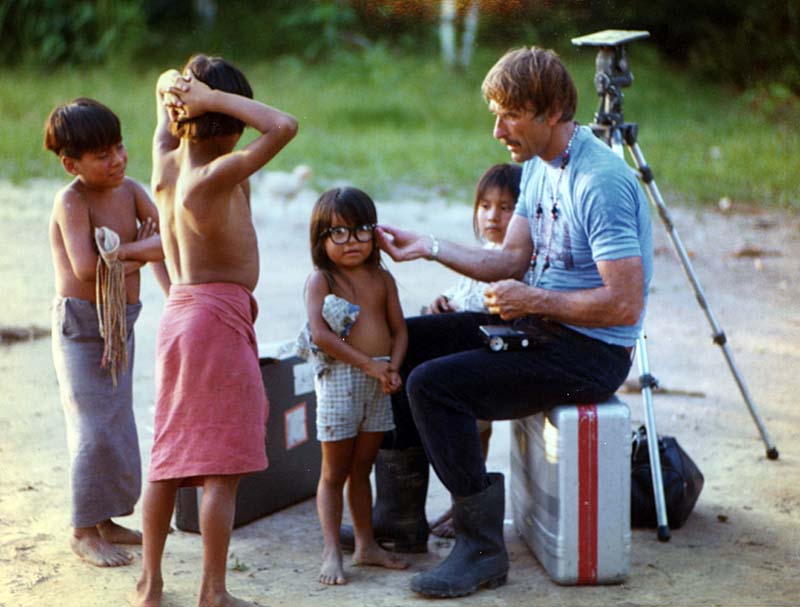

“One particular bright spot: I found a box containing dozens of original Colorama negatives that were never used in Grand Central but are still amazing in their own right,” says Jim Montanus. “I called these the ‘Lost Coloramas’ and had a gallery show at the new Kodak Center in Rochester a couple of years ago. It is an incredible experience as I go through the archive finding imagery from around the world starting in the 50s.”

There are over 100 panoramic photographs that were never selected by Kodak to be displayed as Coloramas.

“One such image – a gritty portrait of ten Rio Street Photographers taken in the 1970s is an instant classic, complete with homemade view cameras fashioned from cardboard and other materials,” writes the Rochester Institute of Technology University Gallery.

Most of the Coloramas were shot by Kodak staff photographers like Neil Montanus, Ralph Amdursky, Steve Kelly, Sam Campanaro, and others. Kodak did commission big names in American photography like Ansel Adams, Ernest Haas, Eliot Porter, Phoebe Dunn, Ozzie Sweet and Ira Spring.

Although Montanus was a staff photographer at Kodak, he operated more like a magazine photographer. During his three and a half decades with the film giant, he traveled and photographed in 32 countries and some of the most exotic places on earth at a time when Kodak travel budgets were unlimited. He shot in Europe many times, Africa, Australia, South America, India, Taiwan, and the South Pacific. He even spent several nights with a former headhunting tribe in the jungles of Borneo.

“I couldn’t have asked for a better job,” said Montanus at age 87 to WROC-TV (channel 8) in Rochester, New York.

According to Jim Montanus, Grand Central Station was about to undergo a major renovation [in 1990] to return it to its original architecture. And this marked the end of an era of Kodak Coloramas. The final image was an apple [referencing Big Apple for New York City] tucked into a glittering skyline as Kodak bid farewell after 40 long years.

You can see more of Neil Montanus’ work on his website.

About the author: Phil Mistry is a photographer and teacher based in Atlanta, GA. He started one of the first digital camera classes in New York City at The International Center of Photography in the 90s. He was the director and teacher for Sony/Popular Photography magazine’s Digital Days Workshops. You can reach him here.

Image credits: All photos courtesy of Jim Montanus, Neil Montanus Estate and Eastman Kodak Company