The ‘Terror of War’ Authorship Conversation Should Go Far Beyond One Photo

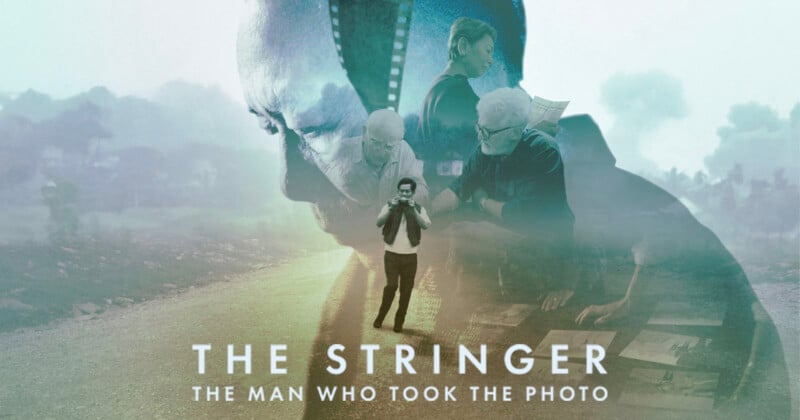

Even before its release on Netflix, “The Stringer” was controversial. But there is much more to the conversation than just who took the famous “Terror of War” photo.

Since “The Stringer” debuted, reactions in the photojournalism community have been swift and unforgiving. Positions hardened almost immediately as people chose sides. The debate quickly collapsed into a blunt question of guilt or innocence, with little room for nuance. Some even refused to watch the film. That resistance included colleagues who strongly support Nick Ut’s authorship and felt the film’s claims did not merit engagement.

I felt compelled to watch the film. I believe ideas should be examined rather than avoided, especially when they provoke strong reactions. If a film’s claims are weak, they will collapse under scrutiny. Refusing to watch it felt like an intellectual dead end. There was also an irony I could not ignore. As visual journalists, we ask audiences to look, to witness, and to examine evidence with care, yet many of us seemed unwilling to view the work we were dismissing. That contradiction mattered to me. I watched “The Stringer” not because I agreed with it, but because I wanted to understand its argument and evaluate its evidence.

After watching it, I recognized that the public fixation on authorship, while understandable, risks obscuring a deeper issue. Authorship matters. It has professional, ethical, and historical significance. But from my perspective as a visual journalist from the Global South, it is not the most urgent question the film raises. More troubling is how the documentary exposes long-standing patterns in how powerful Western news organizations have treated local photographers and stringers, and how easily their labor can be diminished, absorbed, or erased.

At the center of the controversy is “The Terror of War,” the photograph of Phan Thi Kim Phuc, then nine years old, fleeing a napalm attack during the Vietnam War. Widely regarded as one of the most iconic images of the 20th century, it has long been credited to Nick Ut of The Associated Press. “The Stringer” challenges that account, suggesting that Nguyen Thanh Nghe, a Vietnamese freelancer, may have taken the photograph and sold it to AP for a small payment. According to the documentary, Ut received credit as the staff photographer, while Nghe, a stringer, vanished from the historical record. The claim understandably provoked outrage.

The Associated Press has reaffirmed its attribution, citing decades of documentation and internal reviews supporting Ut’s authorship. At the same time, organizations such as World Press Photo have suspended attribution entirely, acknowledging that other photographers may plausibly have taken the image. What remains is a stalemate that leaves no one fully satisfied and no version of events beyond dispute.

The Washington Post published a full-page response by veteran photojournalist David Burnett, one of the few eyewitnesses still alive, who directly challenged the film’s claims. His perspective matters not only because he was present but because it shows how institutional memory and professional authority work to stabilize contested narratives.

Soon after Burnett’s piece ran, Carl Robinson, the whistleblower featured in “The Stringer,” wrote a letter to the editor. Robinson, who worked as a local-hire photo editor for AP in Saigon, contradicted Burnett’s recollections of the scene at Trang Bang. “Journalism demands fidelity to fact, not mythmaking,” he wrote. “Memory, however vivid, cannot override documented truth.” His account added complexity by questioning the reliability of eyewitness testimony and highlighting the institutional pressures that can shape or distort the historical record. Eyewitness memory is imperfect, and archives are incomplete. Had AP produced Ut’s contact sheet from that day, the debate might have ended quickly.

These exchanges reveal something broader. For much of modern photojournalism’s history, Western media institutions have held disproportionate power over archival systems, authentication processes, and the authority to define historical fact. When the archive sits in New York, London, or Paris, and the stringer works in Saigon or Manila, or Kolkata, the power to determine authorship rarely belongs to the person who held the camera.

Technology complicates this further. Tools such as digital forensics and 3D reconstructions can illuminate new possibilities but also introduce new uncertainties. They expand our ability to re-examine history, but cannot fully compensate for gaps in documentation or the structural inequalities baked into archival systems. This tension is evident in the film itself, as The AP disputed the 3D reconstruction analysis conducted by Index, a French independent forensic investigation agency featured in the documentary. No single form of evidence is immune to doubt.

For decades, Western news organizations have relied heavily on local photographers, fixers, and stringers to navigate unfamiliar regions. They provide access, understand the language and culture, and absorb significant danger. Yet they rarely receive the recognition, protection, or long-term benefits afforded to Western staff photographers. While this imbalance is not exclusive to the West, Western organizations have historically held the power to shape bylines, archives, and the official record.

This issue is not abstract to me. I recall conversations with colleagues in the Philippines who worked as stringers for major news organizations. Award-winning photojournalist Victor Kintanar put it plainly: “It seems that every stringer has gone through or experienced something unpleasant from their contractors.” Kintanar began his career as a newspaper photographer in Cebu, worked with The Associated Press and the European Press Agency, and later became a contract photographer for Reuters. Exploitation came in many forms, whether through withheld credit, inadequate compensation, or broken promises. These stories were shared casually, almost with resignation, as if exploitation were simply part of the job. In that context, survival mattered more than recognition. Immediate payment mattered more than a byline.

The film raises the question of why Nguyen Thanh Nghe never challenged the attribution to Nick Ut when the photograph later received awards. The answer is not difficult to imagine. Challenging an institution that controls your income can be risky, and many freelancers learn quickly that upsetting the people who assign work can mean losing work entirely.

I heard similar accounts elsewhere. While discussing the film, I spoke with former colleague Sankha Kar, a veteran photojournalist from India whose career mirrors the challenges faced by stringers across the Global South. Kar began in regional newspapers in Kolkata before photographing for Gulf News in Dubai and freelancing for Reuters.

Despite his experience, he recalled the vulnerability of his early years. “I worked as a stringer without a byline. The photos I took were not archived. Staff photographers would collect images made by others and submit them under their own names.” What lingered was not only the injustice but how normalized it had become. Authorship seemed conditional and easily rewritten by those with institutional authority.

Research supports these accounts. Local journalists and stringers often work without contracts, health insurance, or safety training. They face equal or greater danger than foreign correspondents, yet their names rarely appear in bylines or award citations. According to the International Center for Journalists, local reporters are often “excluded from bylines even when they provide the bulk of reporting from the ground,” a practice that increases risk by erasing visibility and credit. A study in the Journal of Media Practice notes that freelancers frequently accept hazardous assignments without proper support because refusing them can end future opportunities.

‘I worked as a stringer without a byline. The photos I took were not archived. Staff photographers would collect images made by others and submit them under their own names.’

The economic structure behind these practices reinforces the imbalance. Surveys by the Global Reporting Centre and Nieman Reports show that local fixers and stringers typically earn between $50 and $400 per day when working for international outlets, often without contracts, insurance, or long-term security. For news organizations, hiring freelancers is far cheaper than deploying staff correspondents with salaries and benefits. For local journalists, the result is a precarious existence. In the Philippines, full-time photographers earn the equivalent of $360 to $660 per month, with freelancers earning even less. The disparity underscores how risk is pushed downward onto the least protected workers.

Similar patterns appear across conflict zones. In Syria, a report by the Committee to Protect Journalists found that more than a third of journalists killed in the early years of the war were freelancers. In Gaza, restrictions on foreign correspondents mean that local stringers document the conflict under extreme danger, with press-freedom groups recording unprecedented journalist fatalities. In Haiti, UNESCO reports that media workers navigate gang-controlled streets with almost no institutional protection, making it one of the most dangerous places in the world to report the news.

Even the term “stringer” signals disposability. It implies distance from the institution and a lack of permanence. Payment is limited to a single use, protections are minimal, and leverage is rare. For photographers from the Global South, these inequities are compounded by disparities in race, nationality, and economic status.

These issues persist today. Reports from Global Voices document cases of refugee and displaced photographers, including Rohingya journalists, whose images have circulated internationally without proper credit or compensation. Some have faced threats for asserting ownership of their work. These are not isolated incidents. They are symptoms of a global system that values access to images more than accountability to the people who produce them.

Viewed through this lens, the debate surrounding “The Terror of War” becomes something else entirely. The question of who pressed the shutter is less important than the systems that determine whose labor counts, whose work survives, and whose contributions are forgotten. Whether or not Nguyen Thanh Nghe took the photograph, the very possibility of his claim reflects longstanding mistrust in how global media organizations distribute credit and compensation.

This is not ultimately a debate about a single photograph. It is a question of power.

For that reason, the conversation should not end with a verdict on one image. It should begin a broader reckoning with how journalism decides who is seen, who is remembered, and who is written out of history. If the industry hopes to move forward with integrity, it must confront its own practices honestly. That includes fairer crediting systems, stronger protections for freelancers, and a willingness to acknowledge that many iconic images were made by people whose names we may never know.

‘This is not ultimately a debate about a single photograph. It is a question of power.’

Photography asks us to bear witness. Journalism asks us to tell the truth. Both become hollow if we fail to honor the people who risk their lives to create the images that shape our understanding of the world.

About the author: An award-winning visual journalist, Adonis Durado is an associate professor in the School of Visual Communication at Ohio University. Before entering academia, he spent more than fifteen years in media and advertising agencies across Asia and the Middle East. His teaching and research focus on visual communication, immersive media, generative AI, and information design, with an emphasis on how emerging technologies shape authorship and storytelling.

The opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author.