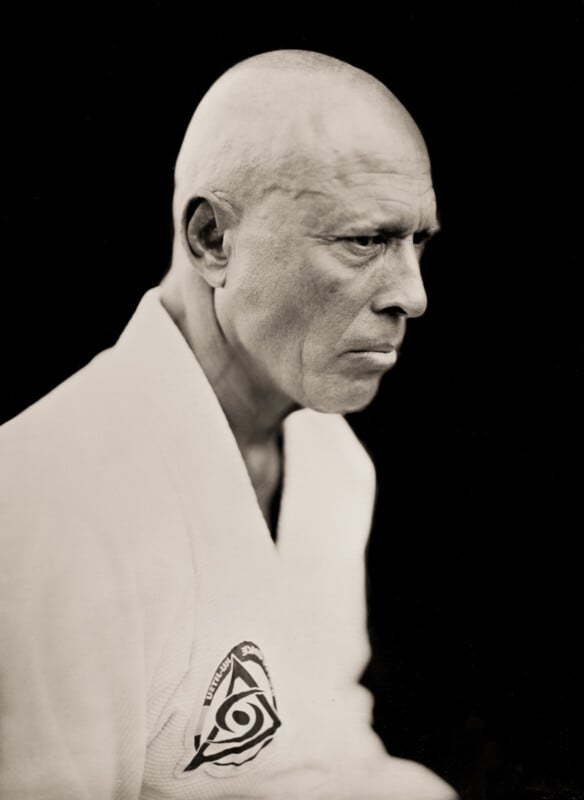

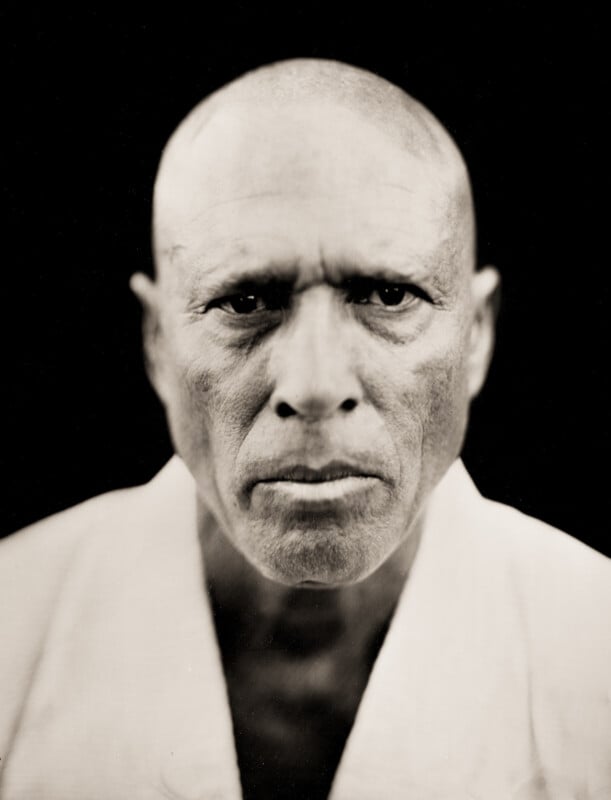

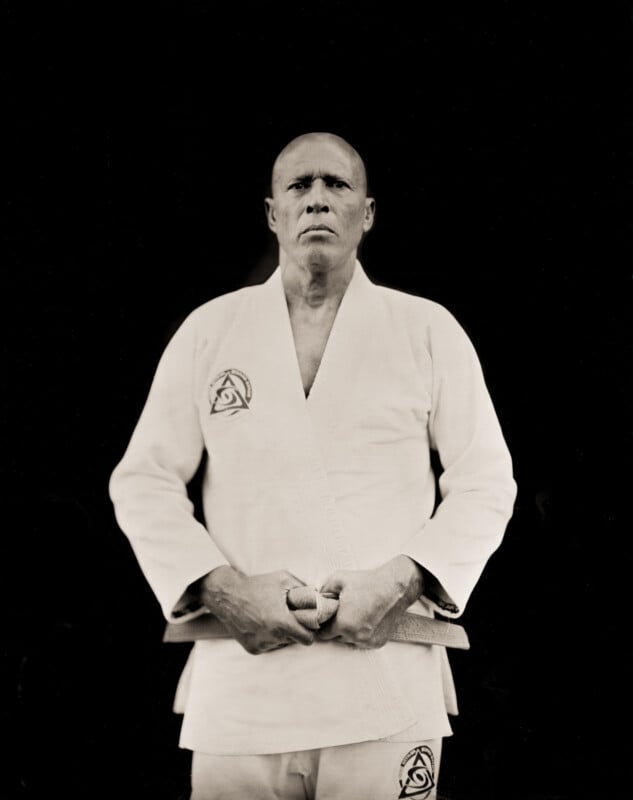

The Father of MMA Captured in Wet Plate Collodion Photography

Most mixed martial arts (MMA) fans can recall the first event, held on November 12, 1993, at the McNichols Sports Arena in Denver, Colorado. It was the dawn of a new era in combat sports. Born from Vale-Tudo (“Anything Goes” in English), UFC 1 was an event that would change the world forever. What was at stake was the determination of which martial art discipline would be most effective if they all came together to fight.

Royce’s father, Helio Gracie, traveled to Japan years before and learned Jiu-Jitsu from the great masters of the time. Helio then took that knowledge back to Brazil, where over the coming decades, he would hone, perfect, and modify the techniques to his choosing. He gave the world the discipline of Gracie Jiu-Jitsu. What is now known as Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu (BJJ) would strike fear into its opponents on and off the mat.

I recall visiting the local video store as a young adult and waiting for the VHS tapes to arrive from the first UFC events. Royce had become a hero; he was the little guy who stood up against Goliath and won. Royce weighed a mere 175 pounds, soaking wet, at the time, and was only 26 years old when he first entered the competition. His fights against the likes of Ken Shamrock and the behemoth wrestler Dan Severn have been written down in history.

Royce would go on to win UFC 1, 2, and 4, and combat sports would be put on notice as to which discipline was most effective at the time, forcing everyone to play catch-up. In the present day, without having BJJ knowledge in the octagon, you do not stand a chance. This is where Royce, as a pioneer, also came into play. The term Mixed Martial Arts was coined because fighters could no longer expect to do well if they competed without a background in multiple disciplines. BJJ became the one discipline that had to be trained, because if you were not, another BJJ practitioner would have a significant advantage over you.

In short, the world owes so very much to Royce and his family for what they have done for the UFC and combat sports. Their discipline has shown us over the years that if you cannot “roll” with a submission expert, you will quickly be submitted, have your arm broken, or be choked out; it is that simple.

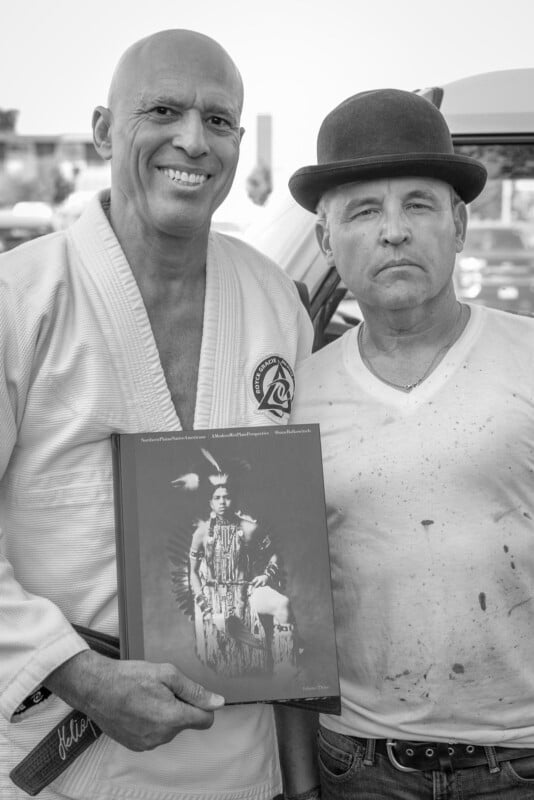

I have been practicing wet plate photography for about 12 years, and Chase Manhart, one of my wet plate pupils, messaged me to say that Royce Gracie is going to hold a BJJ seminar in Aberdeen, South Dakota, on September 27th. Wolfpack Family Jiu-Jitsu was going to host him at the college. I said we need to get his silver-on-glass ambrotype photograph for a museum. I made some calls, and the next thing I knew, Royce agreed to give me an hour after the seminar. The goal was to get one of the original plates into the UFC Hall of Fame, which Royce was the first member of, or the Smithsonian or Library of Congress. Very seldom does a new sport emerge during a lifetime with a single person at its epicenter, but that is the case for Royce. It all leads back to him and his performances in those early years.

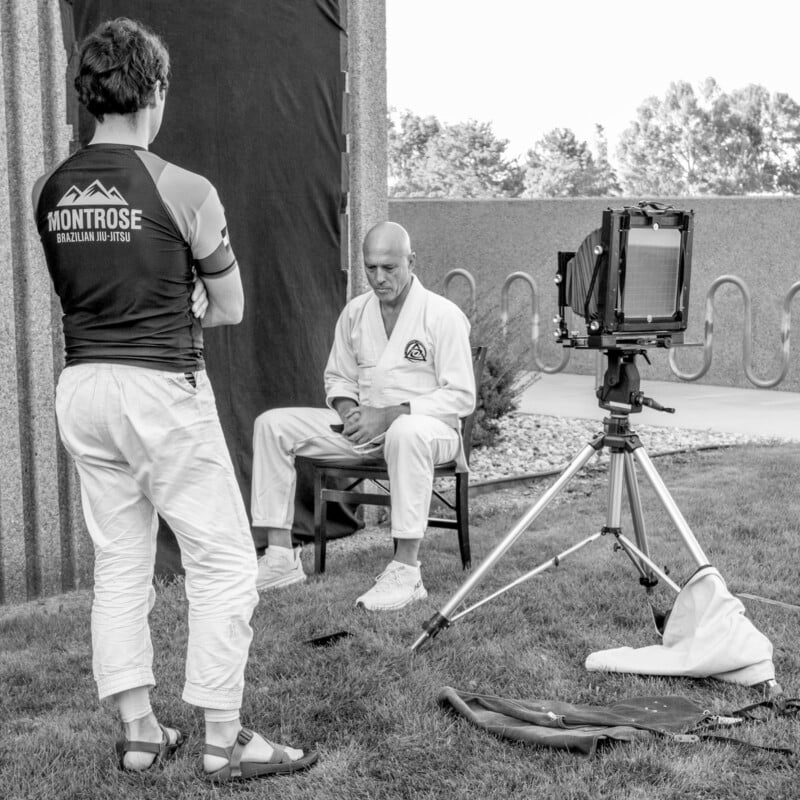

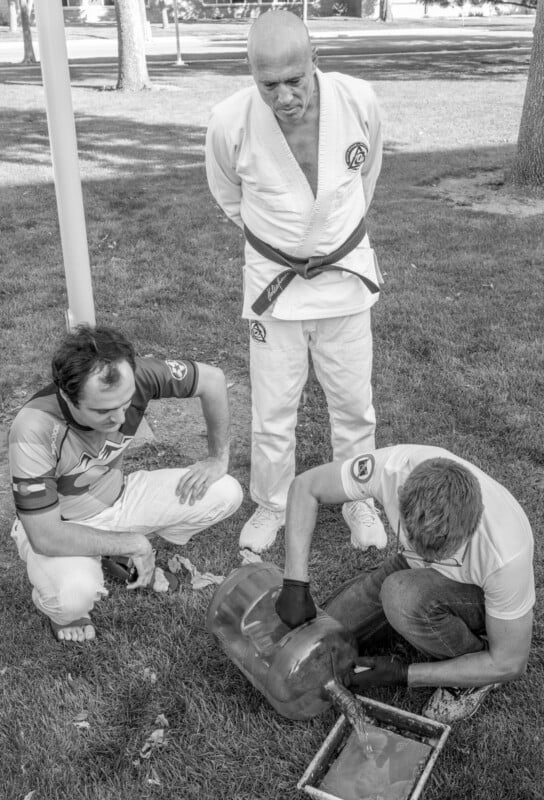

I packed up all my gear, including my large format 8×10 Alessandro Gibellini camera, my portable darkroom, six pieces of cut black glass, and all my chemistry. My 2025 Bronco was full to the gills with equipment, and if anything was missing during my hour with him, a portrait could not be made. After checking my list twice, I was ready for my time with the Champ.

I picked up my good friend, MMA fan, and digital photographer Kelli Swenson on my way. She could document the making of the plates and shoot behind-the-scenes images. I have plates in 107 museums around the world, and it is very important for them to have digital content showing the creation of the plates, proving provenance, and Kelli would fill that role nicely.

We arrived at the location about three hours early and found Royce sitting on the mats of the gym with a couple of young kids.

I walked over and extended my hand, knowing damn well if he wanted to take that arm with him, he could, but that was just in my imagination. He shook my hand and we discussed our time together, and that he had a class to teach. After getting my gear ready for the shoot and setting up my makeshift studio outside the University of Aberdeen, I had a couple of hours to spare. So, I went back into the gym, sat on the mats, and watched the master teach the students some BJJ moves for two hours.

What I learned most about him was not the moves but the life lessons he imparted to the students while teaching them. He had a story and an analogy for everything, and the words he was bestowing upon all of us were so poignant. Here was a man who had seen a few things, and his goal was to pass that knowledge on to anyone who would listen. It was a very magical afternoon.

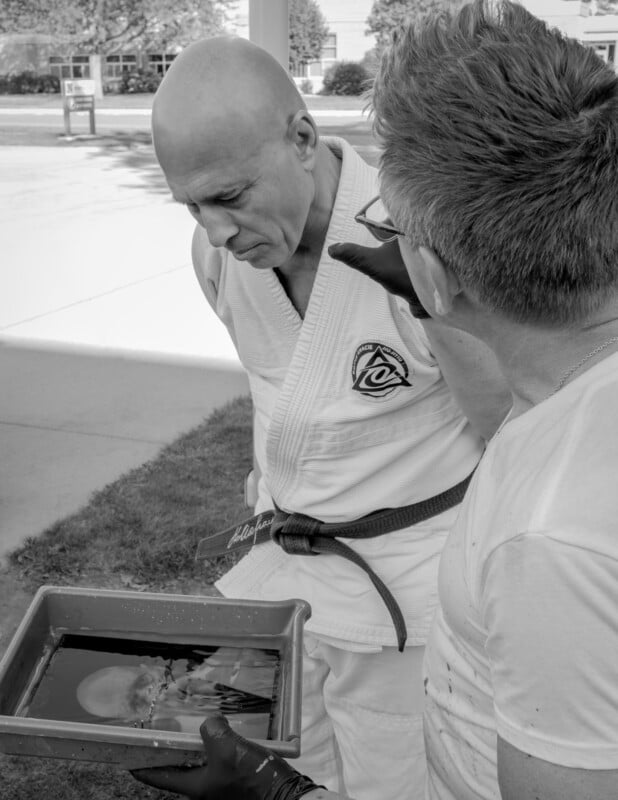

He finished his course, spent time with the students afterwards, taking cellphone photographs with them, and then he came outside for our time together.

I quickly explained to him that this is not like any other photographic process he has ever participated in. The final 8×10 plates will feature his likeness in pure silver on glass, and they will last for 1,000 years, a feat that cannot be said of any other photograph ever taken of the man.

I taped a backdrop onto the outside wall of the university, just like they would have done 170 years ago. We used natural sunlight to achieve the exposure; a flash would not have been sufficient on this day. Royce would have to hold still for 3-4 seconds for the long exposures, and he would need to be disciplined and not move. Who am I kidding? I am asking Royce to be disciplined; he has that in spades, and the long exposure was no match for his mental toughness. I told Royce that we had time for three photos if we were lucky, and the rest is history.

Kelli snapped her digital photographs, which are the black-and-white images used in this article. I made my three plates and shared the entire process with Royce and the crowd of onlookers, who could not help but be intrigued by what we were doing, working out of a Bronco with a large-format camera.

Royce thanked me for my time, gave me a hug, and was on his way to his next adventure and seminar.

Kelli and I re-packed all the gear and headed back to Bismarck, knowing in our hearts that we had captured a piece of history and, more importantly, met a very fabulous human being. I have since received a call from the Library of Congress, and as I type this story, they are deliberating about taking one of the three plates into their permanent collection. As a photographer, it is my job to capture these moments, and what comes after is left up to history.

About the author: Shane Balkowitsch is a wet plate collodion photographer. He has been practicing for over a decade the historic process given to the world by Frederick Scott Archer in 1851. He does not own a digital camera, and analog is all that he knows. He has original plates at 107 museums around the globe, including the Smithsonian, Library of Congress, the Pitt Rivers Museum at the University of Oxford, and the Royal Photographic Society in the United Kingdom. He is a professor of photography at Bismarck State College and teaches a bespoke course on wet plate collodion photography. He is constantly promoting the merits of analog photography to anyone who will listen. His life’s work is “Northern Plains Native Americans: A Modern Wet Plate Perspective,” a journey to capture 1,000 Native Americans in the present day in the historic process. You can find him on Instagram as @balkowitsch.

Image credits: Wet plate collodion portraits by Shane Balkowitsch. Digital black and white photos by Kelli Swenson.