Inside a Covert Cold War Army Base Built Beneath a Greenland Glacier

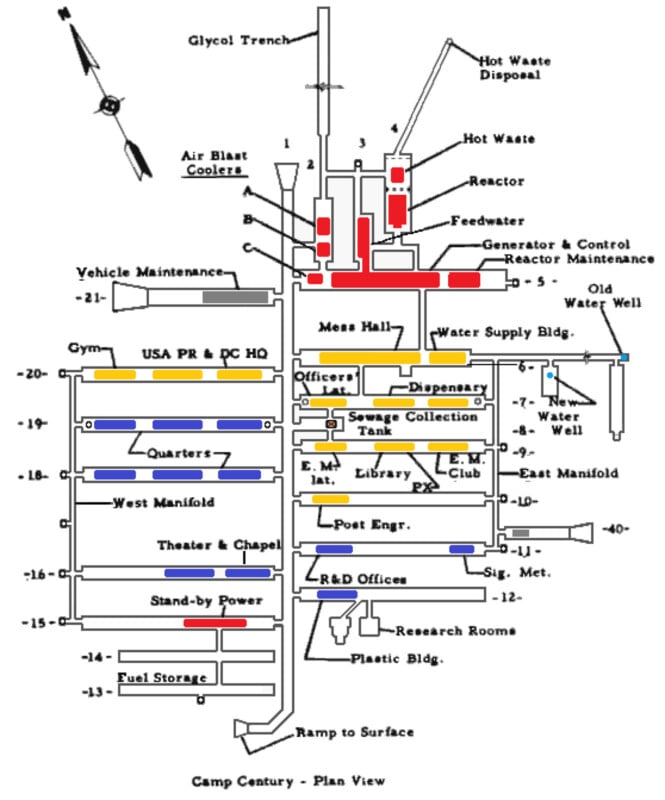

More than 60 years ago, in the far northern reaches of Greenland, the United States Army built an underground scientific research base, Camp Century. Carved into the ice and snow, the nuclear-powered base operated from 1959 until 1967 and comprised 21 tunnels, totaling three kilometers in length.

At the time of its operation, the public-facing objective of Camp Century was to test construction techniques in the Arctic and conduct scientific experiments, including deep-soil analysis. The Army drilled more than 4,000 feet through the ice, eventually reaching the surface of Greenland itself. The extracted ice core was the first ever to penetrate an ice sheet. The work done at Camp Century ultimately contributed to the development of climate models.

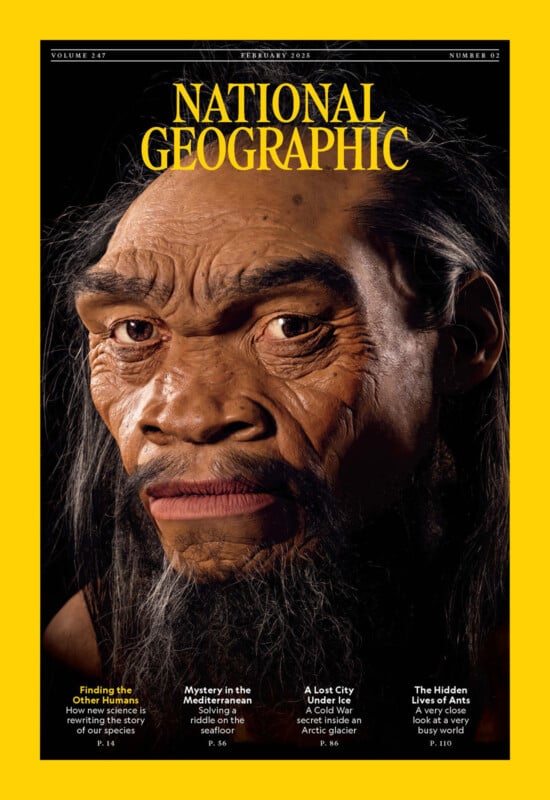

However, as National Geographic explains in a new story, the nuclear-powered Camp Century was much more than a scientific research base and a proof of concept for making the Arctic habitable — it was a Cold War Army project, an ambitious attempt by the American military to build a nuclear missile base that could exert lethal force against the Soviet Union.

Thanks to declassified documents, Camp Century’s secrets are being uncovered. The abandoned and long-secret Project Iceworm was going to take advantage of Greenland’s location and proximity to the USSR and house up to 600 nuclear-tipped ballistic missiles that could be fired over the North Pole at the Soviet Union.

The physical evidence for such an audacious project is long gone, but echoes of the project remain in the form of not only nuclear waste buried beneath the ice but also ancient soil extracted from deep underground. The soil samples sat dormant for decades before being studied just a few years ago by Paul Bierman, geoscientist and professor at the University of Vermont.

Bierman and his team found leaves, mosses, insects, and twigs inside the soil samples, which could have only come from when Greenland was not covered in thousands of feed of glaciers like it is today.

“There are things we can learn about ice sheets that we can never learn from the ice itself,” Bierman says. “It comes from the stuff below the ice.”

People have long thought Greenland’s ice cap is millions of years old, but that’s impossible based on Bierman’s analysis. Greenland must have been ice-free 400,000 years ago.

“What emerges from the data, he explains, isn’t merely an image of the past but also, perhaps, a clearer vision of a future in which quadrillions of gallons of fresh water currently locked up in the Greenland ice cap melt into the ocean. If that happens, the impacts will be felt nearly everywhere, as coastal cities and farms are inundated, potentially turning billions of humans into climate refugees,” National Geographic writes.

Bierman says the soil from Camp Century, which sat in jars in a freezer in Buffalo, New York, and then Denmark for over 50 years, is directly connected to Earth’s climate emergency.

“It takes you from 1966 to global climate change and onward to the effects of Greenland’s melting,” Bierman says. “That’s pretty profound.”

The abandoned Camp Century project and its military underpinnings also relate to geopolitical issues of today, as President Trump is attempting to reestablish not only American influence in Greenland but also to take control of Greenland from Denmark.

There will be no restarting Camp Century, though. The ever-shifting ice caps proved calamitous for the base’s nuclear reactor. The camp was abandoned before its intended lifespan concluded, and it has since been crushed and buried by the icecaps.

“Project Iceworm was doomed from the start. What those Cold Warriors seemed to have miscalculated when they were sketching out their missile tunnels beneath the snow was how much they could prevent glaciers from behaving as if they’re alive. They slide and shrink, grow and flow,” Nat Geo writes.

Soldiers tried to keep the atomic reactor safe as long as possible by constantly cutting back encroaching snow and ice with chainsaws, but it was impossible. The camp’s nuclear reactor was shut down in 1963, three years before Camp Century was entirely abandoned.

“Think of all the energy and resources it took to do this, to build those tunnels and put soldiers down there. It’s almost science fiction. No one would dream of doing that today,” Bierman says.

However, the work the soldiers did more than 50 years ago at Camp Century, while perhaps ill-advised and partially a cover for military expansion in foreign land, has proved instrumental in understanding the climate of today, and the risks the Earth faces tomorrow.

Image credits: National Geographic unless otherwise noted. The story, “The U.S. built a covert Cold War base under a Greenland glacier. Its secrets are now being revealed,” is featured in this month’s issue of National Geographic. The story was written by Neil Shea, with illustrations by Matt Griffin.