Satellite Imagery Shows Huge Mounds on Mars That Could Unlock Secret History

Thousands of mounds and hills scattered across the Martian landscape offer yet more evidence of the planet’s wetter past, according to recent research.

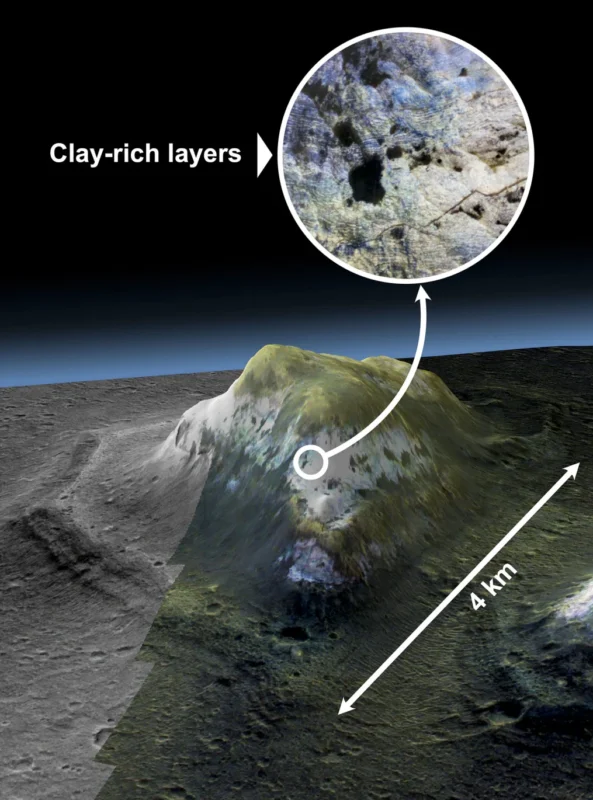

Pulling together high-resolution images and spectral composition data from NASA’s Mars Reconnaissance Orbiters, the European Space Agency’s Mars Express, and ExoMars Trace Gas Orbiter, a team from the Natural History Museum in London revealed that these geological formations contain layers of clay minerals—a clear indication that liquid water once flowed across Mars’ surface nearly four billion years ago.

“This research shows us that Mars’ climate was dramatically different in the distant past,” says Dr. Joe McNeil of the Natural History Museum. “The mounds are rich in clay minerals, meaning liquid water must have been present at the surface in large quantities nearly four billion years ago.”

The Martian Dichotomy and Northern Highlands Erosion

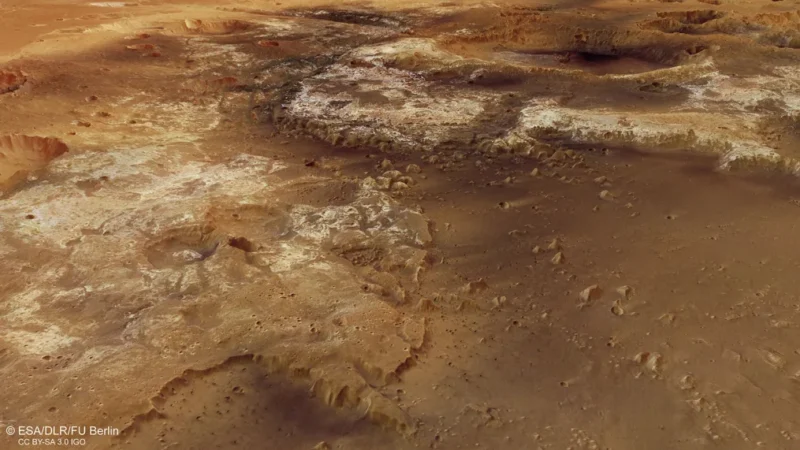

Space describes Mars as a planet of two halves, featuring ancient highlands to the south and expansive, eroded plains to the north. This divide, known as the Martian dichotomy, remains a geological puzzle. The new findings suggest that a significant portion of Mars’ highlands in the northern hemisphere may have been eroded by water, leaving behind these distinctive mounds.

Located in Chryse Planitia near Mawrth Vallis, the mounds range up to 1,640 feet (500 meters) in height and are composed of layered deposits. Some of these layers contain up to 1,150 feet (350 meters) of clay minerals, which formed when water interacted with rocks over millions of years.

“[This] shows that there must have been a lot of water present on the surface for a long time,” says Dr McNeil. “It’s possible that this might have come from an ancient northern ocean on Mars, but this is an idea that’s still controversial.”

Mars’ ‘Buttes and Mesas’

On Earth, formations like buttes and mesas — such as the ones found in the deserts of Arizona and Utah — are remnants of ancient landscapes shaped by erosion. Similarly, Mars hosts its own version of these geological features. The clay-bearing Martian mounds stand as enduring evidence of a time when Mars was a vastly different world.

The researchers believe these formations are the last remnants of a highland region that receded hundreds of miles due to the combined forces of water and wind erosion. The findings bolster the theory that Mars’ northern hemisphere may have once harbored a vast ocean, though as Dr McNeil acknowledges: this idea is contentious.

A Promising Site for Future Exploration

Happily, humans plan to visit Mars and the mounds are considered a prime location for future missions. Notably, the European Space Agency’s Rosalind Franklin rover, set to launch in 2028, is expected to explore the nearby Oxia Planum region.

“The mounds preserve a near-complete history of water in this region within accessible, continuous rocky outcrops,” Dr McNeil adds. “The Rosalind Franklin rover will explore nearby and could allow us to answer whether Mars ever had an ocean and, if it did, whether life could have existed there.”

Understanding the formation of these Martian mounds could also shed light on early Earth. Mars lacks plate tectonics, which means its ancient geology remains largely intact. “Mars is a model for what the early Earth could have looked like,” Dr McNeil explains. “Looking at early Mars helps us to understand the early Earth, and as more missions visit the red planet, the more we’ll be able to dig into our own planet’s history.”