WuvDay App Turns Smartphone Users Into Verified and Paid Journalists

![]()

Italy-based WuvDay aims to fight against fake news and deepfake content by utilizing the smartphones average people hold in their hands through an onboard verification platform.

The general idea is to offer access to GPS and timestamped photos and video taken from smartphones through the app, all of which confirm the location and metadata to confirm there was no editing or manipulation. Media outlets can request or purchase available content to use themselves, with the money going straight to those who shot the images or footage.

WuvDay demonstrated its app and website at the Mobile World Congress (MWC) in Barcelona as part of an Italian delegation of small companies and startups. Though based in Italy, the app is globally available on iOS and Android and applicable to anyone, while the website works on all browsers. It currently supports five languages: English, Italian, Spanish, French, and Portuguese. WuvDay’s CEO Giuseppe Carapellese spoke with PetaPixel to explain how it works and what to expect.

Combating Fake News

Carapellese cited generative AI platforms, including OpenAI’s Sora, as vital reasons to develop something like WuvDay, which wants to ensure that the content is both authentic and accurate. That’s where the GPS and timestamp verification comes in, though the key to it all is that you can only capture images within the app, which mandates that those details be irrefutable. When you take a photo or video in the app, location, time, and metadata are tamper-proof, ensuring outlets know what they’re buying.

Citizen journalism isn’t necessarily new, and media outlets routinely use on-the-ground social media posts to visualize an event or incident in their reporting. The difference is social media platforms don’t verify the authenticity of the content or if the person posting it is who captured it. Plus, content on WuvDay doesn’t come out looking compressed the way it would on Instagram or TikTok, so there is a quality control element to it as well.

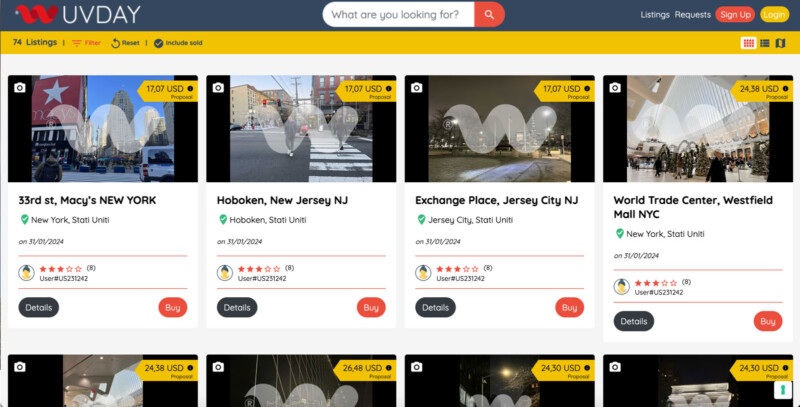

Users can post whatever they want that may have some news value or take on what’s called a “content request” from media looking for something more specific based on location or event. Examples on the site include political events in Italy and other European countries, along with sporting events, war-torn scenes in Ukraine, and a fire in Valencia that occurred only a few days before MWC. There are about a dozen different categories covering everything from emergency scenes to entertainment, culture, travel, sports, politics, religion, and science and technology.

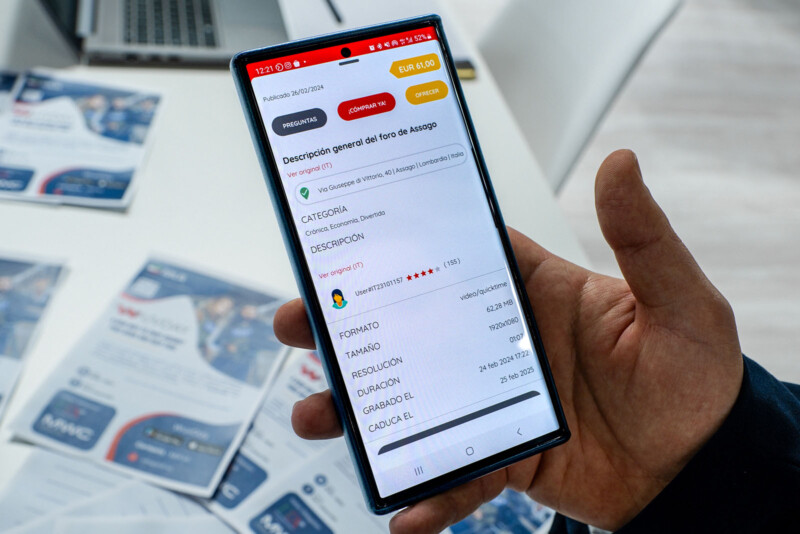

Requests can be for a certain number of photos or video clips that can be short or considerably longer, like 15 minutes. Timestamps are just as crucial because they ensure older content in the same location isn’t repurposed, as has often happened on social media.

Embedded Google Maps data in the app points to the exact location of the requested coverage, including an address and details of what the assignment requires, be it a landscape video of a particular duration that avoids sudden movement throughout. Video doesn’t need any voiceover, so like photos, much of the content is made up of point-and-shoot scenarios.

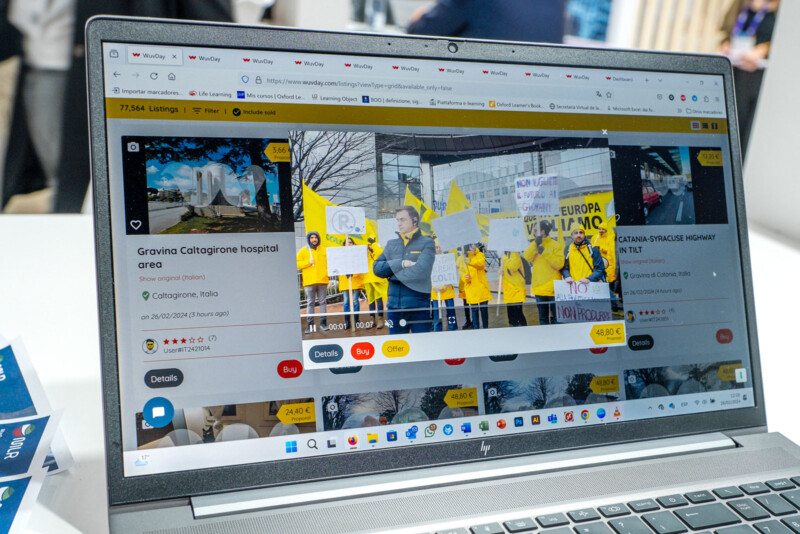

To lock things down further, all posted photos and videos have watermarks until purchased. Once purchased, the creator loses ownership over it, so they can’t resell it multiple times. In that respect, outlets are buying the content and the license to use it however often they want. Moreover, it’s not possible to screen record or screenshot images or playback on WuvDay, cutting off a potential workaround for skirting restrictions.

Usability and Payment

WuvDay makes its money with a transaction fee that is transparent to all sides. Selling content means you receive the full amount, while buyers pay a total amount that includes the extra cost, so there shouldn’t be any surprises for either party.

When it comes to payments, some of the fees for content requests are modest or minuscule. For example, a simple two-minute video of a scene at MWC was fetching about $7 or $8 (the app and site offer conversions for every currency). That’s not much, but perhaps it is relative to the time it takes to capture and upload the content. Some uploaded content, which falls under the “proposal” section, seeks more money from would-be buyers.

![]()

It is possible to take multiple images and clips before selecting the ones you want to submit, and WuvDay suggests best practices, like avoiding backlit subjects and watching out for detail in low-light conditions. With very few exceptions, everything is in landscape orientation, making this feel like the opposite of what’s standard on social media.

Carapellese says WuvDay will soon implement a new feature that segments content into “breaking news” and another called “archive.” Breaking news would open up more exclusive arrangements between buyers and sellers who can negotiate a fee for similar content types. In contrast, archived content will have fixed fees without exclusivity, meaning users can sell it on the platform as many times as possible.

![]()

There are currently 120,000 users, with more recent growth coming from the United States and Asia, though both are still dwarfed by the sheer volume coming from Europe. Still, Carapellese says some European outlets look for content that may be relevant to stories from other parts of the world, which he sees more of now.

Turning Smartphone Users into Reporters

While the content’s authenticity is easy to verify on the platform, the context may be more complex. Users posting content can write blurbs explaining details about what happened or any specific points that may not be obvious from the images. Those may be harder to verify, though buyers can always ask sellers questions in case of confusion or missing details.

![]()

WuvDay’s openness also makes it an option for would-be reporters in poorer countries to benefit from the platform, especially where every dollar or euro earned stretches further. It could also be potentially dangerous, especially for those trying to capture content in war-torn or crime-ridden locales. The focus on authenticity could push users to be more creative to stand out, no matter where a user is, especially since there is no way to utilize the AI-driven computation and editing features that continue to grow in smartphones. What a seller sees is supposed to be precisely what a buyer gets.