High-Resolution Thermal Satellite Takes Earth’s Temperature

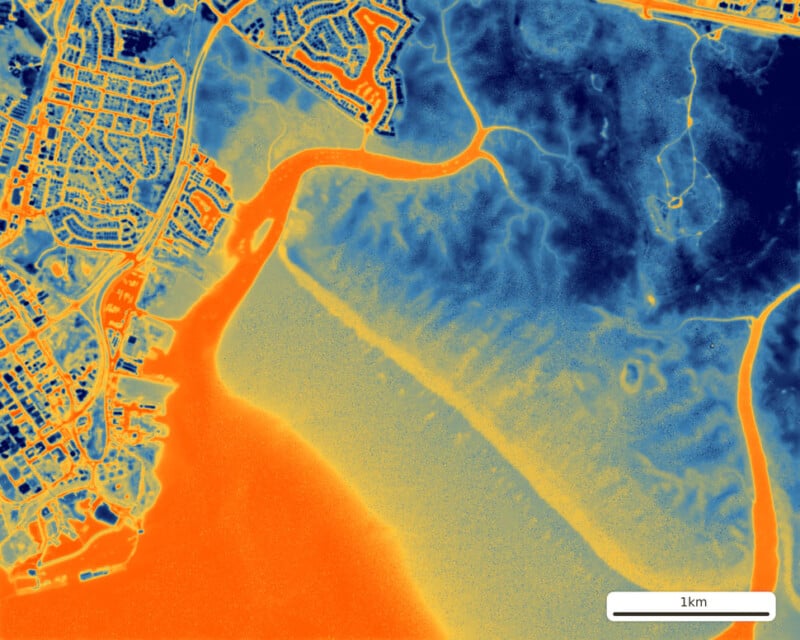

A new high-resolution thermal satellite camera has beamed back its first set of spectacular images.

The recently launched HOTSAT-1 captures thermal images from space revealing the planet’s surface temperature in never-before-seen detail. It can show temperature differences down to a resolution of 33 feet, according to Space.

The camera can also capture short video sequences and one of them shows the thermal signature of a train as it rolls through Chicago.

#HotSat1, the "thermometer in the sky" 🌡️🛰️, is now acquiring high-resolution thermal maps of the built and natural environment. Here, the heat signature of a locomotive 🚂 is seen moving through the night in #Chicago. "Cool" stuff. @satellitevu https://t.co/PvrTpx7xPU pic.twitter.com/EKPX6OB3Xq

— Jonathan Amos (@BBCAmos) October 6, 2023

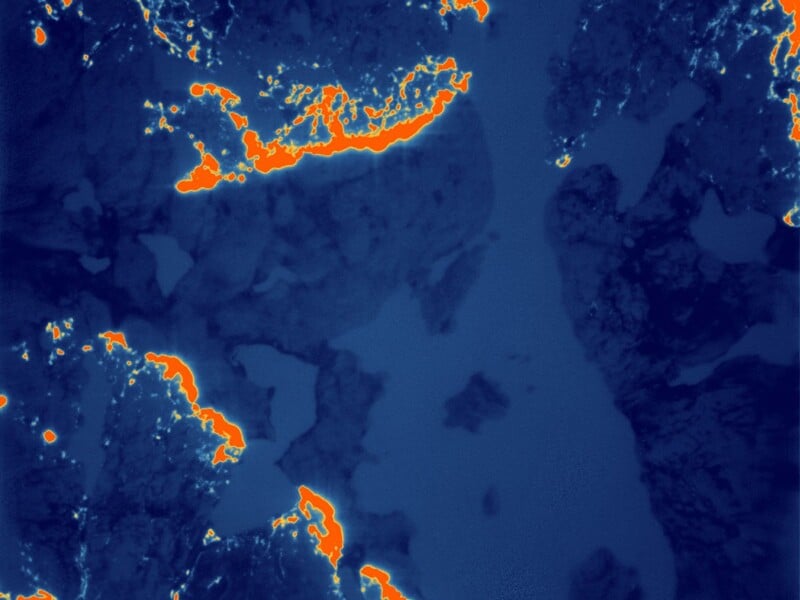

One of the images captured by HOTSAT-1 shows the thermal footprint of a wildfire that hit Canada’s Northwest Territories in June and the hope is that the data will help firefighters monitor how fires advance on the landscape.

HOTSAT-1 is operated by British company SatVu which plans to launch seven additional spacecraft that will not only increase the volume of data but also detect thermal changes in a scene more rapidly.

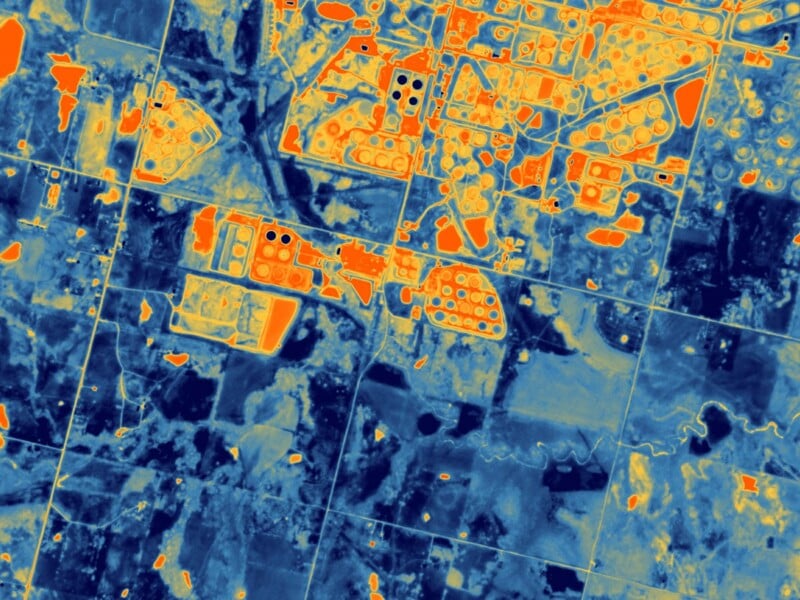

“Thermal imaging has been done for decades by scientific missions like NASA’s Landsat and the European Sentinel satellites,” says Satvu’s chief technical officer and co-founder, Tobias Reinicke.

“But these satellites are only collecting thermal data at a very coarse resolution — 100 meters, 500 meters, or 1,000 meters [330 feet, 1,650 feet or 3,300 feet]. There’s not been a commercial mission that is capturing data under 10 meters [33 feet] in the thermal spectrum.”

Analyzing temperature differences on the Earth’s surface in high resolution will help city planners gain a better understanding of how heat escapes from roads, buildings, and industrial areas. The hope is that it will lead to more energy-efficient infrastructure.

Most satellites observe Earth in visible light, i.e. the same wavelengths that humans see with their eyes. The HOTSAT-1 satellite detects heat which is essentially infrared light, a far longer wavelength which presents a challenge.

“You need a slow shutter,” Reinecke tells Space. “Effectively a longer exposure. But because our satellites travel through space at a speed of 7 kilometers per second [4.4 miles per second], we need to be able to carefully point the satellite; otherwise, the images would be blurry.”