A Photographer’s Journey to One of the World’s Holiest Places

A Nat Geo photographer, Ziyah Gafić, recently traveled to Jerusalem to capture unprecedented images of the Dome of the Rock, one of Jerusalem’s holiest and most controversial landmarks.

Alongside being a National Geographic photographer, Gafić is the Director of VII Academy, an organization dedicated to providing visual education courses to help empower the next generation of journalists in regions that are underrepresented on the global stage.

Experiencing Conflict During his Formative Years has Changed Gafić’s Perspective

Gafić grew up in Sarajevo, the capital of Bosnia and Herzegovina, during the city’s siege. He briefly became a refugee in Italy before returning home, crawling through a tunnel beneath Sarajevo’s airport to meet his father, an essential figure in the city’s resistance.

“Having experienced conflict in my formative years (I was a teenager) leaves permanent traces on one’s psyche. Most of those are negative; I wish I never had those experiences. However, it dramatically affected my worldview and sparked my interest in conflicts,” Gafić tells PetaPixel.

“Being raised under the siege and being a refugee leaves you with a siege mentality and a never-ending feeling of being uprooted. Ultimately, I believe it makes it a tad more manageable for me to understand what someone at war is going through and makes it easier to empathize with the person in front of the camera, which is probably half of the photograph already. I take that experience wherever I travel — whether war or not- Baghdad, Kabul, Grozny, New York, or Jerusalem,” he continues.

An award-winning photojournalist, author, speaker, and National Geographic contributor, Gafić knows first-hand what it is like to grow up in a city with a highly complex and, at times, violent religious culture. Sarajevo, often called the Jerusalem of Europe, is one of the few major European cities with a mosque, catholic church, Eastern Orthodox church, and synagogue, all within a single neighborhood.

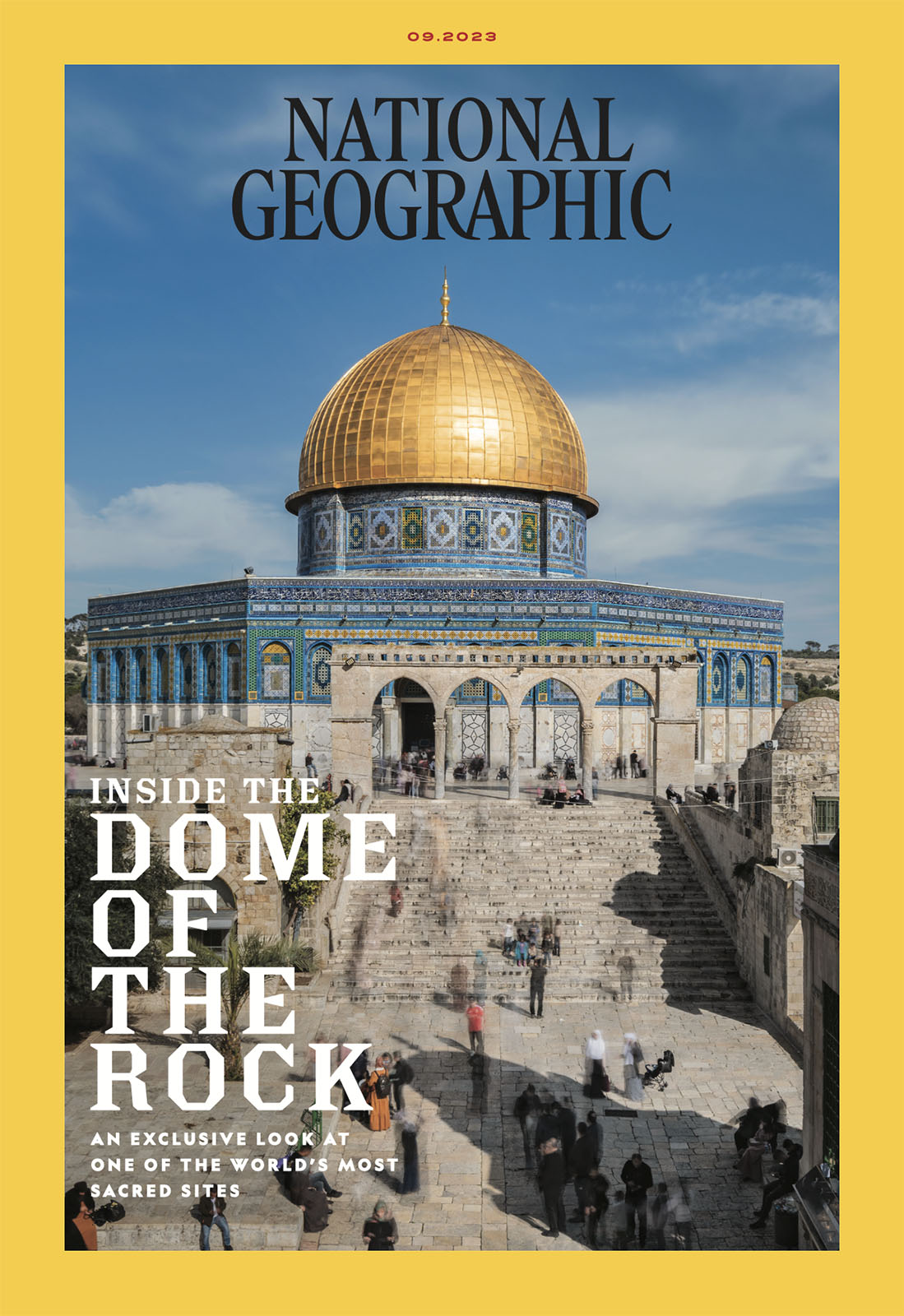

Sarajevo’s religious diversity and cultural importance align nicely with Jerusalem and Gafić’s beautiful subject, the Dome of the Rock. Nat Geo writer Andrew Lawler describes the sacred building as “a place of both prayer and protest.”

The Dome of the Rock

“Any viewer’s tongue will grow shorter trying to describe it. This is one of the most fantastic of all buildings, of the most perfect in architecture and strangest in shape,” exclaimed traveler Ibn Battuta during a 1326 visit to Jerusalem.

The Dome of the Rock’s remarkable age is but one of its incredible characteristics. While the Islamic shrine at the center of the contentious Al-Aqsa mosque compound in the Old City of Jerusalem has undergone many renovations throughout the centuries, its initial construction dates back to the era of the Second Fitna in the late 600s.

The building has stood throughout so much disorder, war, and upheaval in the region, both within the Islamic population and the entire area surrounding Jerusalem. It has been damaged, including by a severe earthquake in the early 20th century, but today, the golden dome stands proudly against the backdrop of the historic Old City.

“The Dome of the Rock has miraculously survived looters, earthquakes, religious strife, bloody invasions, and more prosaic threats like pigeon droppings clogging its drainpipes, sending rainwater trickling into the walls. Its striking image adorns coffee mugs, tea towels, and screensavers, and framed pictures of its dome hang in mosques, living rooms, and public buildings around the world,” Lawler explains.

“Almost two billion people are connected to this place,” explains Sheikh Omar Kiswani, director of the 36-acre religious complex, adding that praying at the sacred place is worth “500 prayers elsewhere.”

Security, Permits, and Unpredictability Made the Project Challenging

The importance of the Dome of the Rock, the reverence that Muslims have for it, and the fraught location in which it exists, all posed unique challenges to Gafić.

Alongside requiring security clearance, which took multiple years of negotiations, there were daily challenges with entering the sacred grounds.

“The Noble Sanctuary, as Muslims refer to it, or Temple Mount, as Christians and Jews call it, and the Dome of the Rock, as an integral part of the complex, are under the control of Jerusalem Islamic Waqf (endowment) — authorized by the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan. However, Israeli security forces control the entrances to the complex. We primarily dealt with and agreed on access to the site thanks to the contacts in the Embassy of Jordan in DC and our contacts on the ground in the office of Waqf. As per the status quo from 1967, The Waqf is the custodian of the Noble Sanctuary. However, it also meant that upon every visit to the site, we had to go through Israeli security checkpoints (per the same agreement, Israel is responsible for the site’s security),” Gafić tells PetaPixel.

He has worked in the Middle East since 2002 and is no stranger to strict security and checkpoints. However, his experience also meant that Gafić had doubts as to whether, when he arrived, he would be allowed into the areas he wanted to photograph.

“I knew that no previous agreement might survive the first contact with the reality on the ground. However, knowing that our contacts were high-ranking officials and under the National Geographic banner, I was convinced we would see things people are usually not in a position to see. I was hoping we would get the opportunity to get to the most crucial places, and without those, there would be no story,” he explains.

A constant source of struggle on site was Gafić’s tripod being confiscated. He says that he is a slow, methodical photographer and primarily shoots with medium-format equipment, which means that it is challenging for him to be “a fly on the wall.”

The Israeli Government Press Office issued him a press card, which he says made his job more manageable. Nonetheless, the Noble Sanctuary has a special status, so what flies outside the grounds may not necessarily be permitted within them. He was at the whim of the officers on the ground, regardless of what he had been assured beforehand.

“My fixer brought in the gear to avoid lengthy and unpredictable negotiations with the security forces daily, and we kept the equipment in the sanctuary. At the same time, I would just take memory cards out for offloading and batteries for recharging. On one occasion, while photographing one of the gates to the Noble Sanctuary, we were approached by the police patrol, taken away, and then waited for hours just to be let go — without explanation. I want to believe that was just for the security background check. On another occasion, a different police patrol politely confiscated my tripod, later to be returned at the intervention of the Waqf. Obviously, it’s not my first time working in places where cameras are not welcome — so patience goes a long way,” Gafić tells PetaPixel.

The Importance of a Photo Editor

While there, Gafić captured more than 20,000 photos. PetaPixel asked about the role of his photo editor at National Geographic and how they help with sorting through images and picking the perfect shots to illustrate any story.

“I was fortunate to work with James Wellford, an editor at the National Geographic magazine. We’ve worked together since Jamie’s time at Newsweek and later at The Smithsonian. He’s known me since I was 23 years old aspiring photojournalist. So there was an implied trust from him as an editor who put me up for the story, knowing what I could and couldn’t do and me as a photographer. There was no doubt the edit would be surgically precise. We had countless calls and editing sessions before the finalized revision was presented to the Magazine. At the same time, a whole team was working on putting together the story for various platforms. In the field, I worked alongside a veteran writer, Andrew Lawler, whose deep knowledge of Jerusalem and calm but confident approach to the subject made me blush twice a day,” says Gafić.

Adventures in Jerusalem

Some of Gafić’s more adventurous photography required a sense of calm. Armed with his camera and a background in rock climbing, he scaled the iconic golden dome itself.

“It is impressive that you are climbing a structure over 1300 years old and under heavy surveillance, so it was bound to raise eyebrows everywhere. To capture the Noble Rock or the Foundation stone, I had to squeeze myself into this narrow ledge (about 50 centimeters wide) between the outer and interior dome — without any fence and extend as much as possible to have a rock in the center of the frame. For someone who is six feet, two inches, narrow spaces don’t really agree with me,” he says.

The Dome of the Rock’s Incredible History, Uncertain Origins, and Fraught Future

While the Dome of the Rock has survived for over 1,300 years amid considerable turmoil, its future remains contentious.

“Conflict in Israel and Palestine was one of my first international assignments (back in 2002), so I knew what to expect. A lot of security, questions at the airport, endless negotiations, and careful navigation. One of the critical points in this ongoing conflict is the future of the Dome of the Rock — which makes everything exponentially more complicated. Given the nature of this relatively low-intensity conflict, I knew it would be realistically safe for me to operate,” Gafić says.

Lawler describes that the Dome of the Rock “stands at the center of one of the world’s thorniest geopolitical disputes, and its golden vault is a frequent backdrop to violent confrontations between Palestinian worshippers and Israeli police.”

“Any church or synagogue in the Holy Land is a place of peace. Only here is it a war zone,” explains Sheikh Kiswani.

While Muslims revere the shrine as a crucial religious location, and Palestinians in particular consider it a vital symbol of their nation, many religious Jews want the structure destroyed and replaced with a Jewish temple. Certain evangelical Christians think the site may be ideal for a temple to kickstart the return of Christ.

Unsurprisingly, this mix of fervent religious conviction is a powder keg in a region with a long, strong undercurrent of tension that occasionally boils over in deadly ways.

Given the age of the Dome of the Rock, its uncertain origins are understandable. 1,300 years is a very long time, and not all knowledge is passed down from generation to generation. Historians are still hard at work trying to learn more about the “why” and “how” of the Dome of the Rock.

Even as so many Muslims enter the grounds daily to pray and feel closer to god, people are hard at work in the background, trying to get to the building’s roots.

In the early 1990s, these metaphorical roots became physical ones during renovation. To remedy a poor renovation by an Egyptian team in the 1960s, King Hussein of Jordan sold his home in London to raise the money required to renovate the dome. He spent over $8 million on 176 pounds of 24-karat gold plating to gild the dome’s exterior. Workers also replaced aluminum and concrete components with more traditional materials, like mahogany and lead. The current king of Jordan, King Abdullah II, remains the holy site’s custodian while Israel controls the security.

King Abdullah II is overseeing ongoing restorations, although progress has been slow. Jordanian and Al Aqsa officials blame Israeli police for the sluggish repairs.

Even with some renovations hanging in the balance, the Dome of the Rock and its surrounding compound offer considerable splendor and beauty.

“The visual part of the story focuses on the ingenuity of the structure and the historical and cultural importance of the site. I see the Dome of the Rock as a living monument — to borrow from the vernacular. It is a structure that has been around for over 1300 years in its present form and is used daily by worshippers. It was relatively clear to navigate visually within those set parameters. This space is controversial in religious beliefs and politics, not so much in the visual realm,” Gafić explains.

The VII Academy

Alongside Ziyah Gafić’s fantastic work as a photojournalist, he has also been instrumental as the Director of the VII Academy.

“VII is synonymous with courageous and impactful journalism, and the founding members all met in Bosnia during the war when I was a child. VII was founded years later in 2001 and came to prominence during the aftermath of 9/11, the war in Afghanistan, the invasion of Iraq, and all that followed. Given its history here in the Balkans, its prominence when I was starting my career, its focus on human rights and the experiences I witnessed firsthand as a child, it has always been an organization that was close to me,” Gafić explains.

He continues, “The digital revolution that enabled the photographers to build VII also precipitated an undeniable loss in revenue for their media clients. Anticipating this shift, Gary Knight and Ron Haviv created the VII Foundation to explore new ways of supporting large visual projects.”

“Brilliance and bravery don’t come from nowhere, they have to be nurtured and mentored. Some of our alumni are coming from the most vulnerable communities and they work and live in the most hostile environments – like Myanmar, Ukraine, Mexico, Congo, etc. With less opportunities, shifting business models and a general lack of training and mentoring opportunities the work we are able to do has never been more important,” Gafić adds.

“I believe that as a director of VII Academy I can contribute much more to the photographic community than I could possibly do as a photojournalist,” he remarks.

Image credits: All images © Ziyah Gafić for National Geographic. Lawler’s story, “An unprecedented look inside one of Jerusalem’s holiest — and most controversial — landmarks,” is available now in the September issue of National Geographic.