The Alluring Beauty of Ben Horne’s Large Format Film Landscape Photos

Prominent large format wilderness photographer Ben Horne has enchanted viewers with incredible landscape and nature photography, primarily of the American West, for over a decade.

On his YouTube channel, Horne offers viewers an in-depth look as he journeys out into the field with his large-format gear, scouts locations, and captures photos. Horne also does film reveal videos, which pair nicely with his in-field videos, as he surely can’t develop his large-format film photos out in the wilds of the American West.

PetaPixel chatted with Horne to discuss his photographic journey, his short-lived foray into digital cameras, and how working with large-format analog technology has enriched his artistic experience.

Ben Horne’s Photographic History — The Early Days of Digital and the Move to Analog Technology

Born and raised in San Diego, California, Ben Horne has long put his experiences in the American West to photo paper. Growing up in the 80s, Horne used a point-and-shoot film camera.

As a high school student, he took a photography class and became serious about photography as a hobby and art form. “We worked with 35mm film, developed it ourselves, and made prints in the darkroom,” Horne tells PetaPixel.

This was in 1998, so digital photography was in its nascent stages as a commercial product for professionals and, to a lesser extent, typical consumers. Horne says his first digital camera was only 0.3 megapixels and recorded photos on floppy disks.

![]()

While new cameras these days usually offer only iterative improvements over their predecessors, back in the 90s and early 2000s, every new camera was a significant innovation. Groundbreaking technologies arrived in a fast and furious fashion.

At this point, Horne was all-in on digital photography gear. “I rode that early wave of innovation with a variety of cameras, including Canon’s first digital SLR, the D30. From there, I went on to own a variety of pro-grade Canon cameras, including the 1D, 1D Mark II, 1Ds Mark III, and 5D, and was well-versed with digital.”

However, Horne found the process to be wildly unfulfilling.

“If I were to take a photo I was very proud of, that sense of satisfaction would fade with the announcement of a new camera. Would a once-in-a-lifetime photo captured on a 3-megapixel camera stand the test of time? I was caught in the endless cycle of upgrades, all while chasing a sense of perfection that — quite frankly — doesn’t exist,” Horne laments.

A Return to Analog

In 2008, one of Horne’s friends suggested that because of his interest in landscape photography, he should try a 4×5 film camera.

“I purchased a used Toyo 45AII 4×5 camera and took that along with my 1DsIII on my first solo landscape photography trip — and the rest is history,” he explains.

“I loved the process of working with a mature technology. It gave my work a sense of permanence I didn’t experience with digital. A photo captured on 4×5 today will be the same as an image captured on 4×5 film 10 years ago as well as 10 years from now. Also, large format teaches you to embrace the imperfection of the craft — resulting in a greater sense of satisfaction. Not long after that trip, I sold my entire digital kit,” Horne says.

For the past 15 years, Horne has been a large-format film photographer, and it’s helped propel him along an incredible artistic journey full of beautiful photos and a rich collection of videos documenting Horne’s photography adventures.

After starting with 4×5, he purchased an 8×10 camera shortly after that. “I first bought a 4×5 to see how I liked working with large format — and it was love at first sight. After getting my toes wet with 4×5, I purchased an 8×10 a short time later, which I had secretly admired since learning about large format. Truth be told, I could have stopped with 4×5 and have been fine, but there was something about the lure of working with an 8×10. The process of working with both formats is about the same, but the depth of field is narrower on 8×10, the film is four times the cost, and the cameras are bigger and heavier,” Horne says.

The Role of YouTube in Horne’s Work

Horne’s YouTube channel is where many people have discovered his outstanding work. It has enabled a new generation of photographers to learn about analog photography in the digital age, and it’s an interesting juxtaposition to watch the creation of analog photos on a digital platform.

“That’s really cool that you were introduced to large format through my channel. In many ways, my channel flies under the radar. My goal is to simply show what I’m doing and explain why, but not to tell people how they should go about their photography,” Horne says.

Horne puts effort into his YouTube channel, although he doesn’t want it to “become ‘work,'” which is one reason he doesn’t show ads on his channel and never resorts to clickbait. Despite the incredible quality of his work, his subscriber count trails some other photographers who make similar content, albeit only sometimes with Horne’s analog flavor.

Perhaps because Horne shoots in a format very few photographers use, it limits his reach. However, that doesn’t bother him.

“Channels depending primarily on ad revenue are rewarded by the number of views their videos receive, which is why so many channels become so formulaic with the strange facial expressions in thumbnails, odd numbers of tips and tricks, and sensationalized titles with ‘STRANGE’ use of ‘CAPITALIZATION’ for emphasis,” he explains.

“For me, that would make photography into work, which I have no desire for. By shutting off the ads and not playing the clickbait game, I can focus on producing videos that are more personally meaningful. I’ve found through the years that this also attracts a higher quality audience — an audience that’s incredibly supportive. I went with the viewer-supported content route back in 2010 via PayPal, and then more recently with Patreon — which allows me to do what I love, and for photography not to become work,” he continues.

Perhaps it’s unsurprising that a photographer like Horne, who pours so much into every single frame, would be of a “quality over quantity” mindset. While that means he isn’t getting huge subscriber and viewer counts, he has built a tight-knit, supportive community, and that’s much more important to him.

He’s also inspired others, which is a fantastic achievement for any photographer, no matter the gear they use.

“I know quite a few people who have tried large format after watching my videos through the years, most of which still use it to this day. There’s something so very satisfying about the process of working with mature technology, and I’m glad it’s something other people are able to experience as well,” Horne comments.

PetaPixel asked Horne about the potential for offering workshops, but he says he has no plans for that. He enjoys the solitude of his photographic process and is worried that introducing clients into that would be anxiety-inducing and make photography feel like work.

“Who knows what the future holds, though,” he adds.

Balancing Photography and Video in the Field

PetaPixel asked Horne how he handles video content creation in the field, given his primary purpose is making great photos.

“Photography always comes first. In most cases, I arrive well ahead of the light and have time to record the footage I need in relaxed fashion, but if I’m driving along and see a rapidly changing scene I’d like to photograph, the video kit stays in my truck. There are always creative ways of making a video work after the fact with voiceovers and such,” Horne explains.

He used to try to film enough videos to create a new video for each day of a photo trip. However, he has since moved away from this approach, as it put a lot of pressure on him to record constantly.

“Now I just record whatever feels necessary and worry about it after the fact. Combining several days into a single video is fine with me — just so long as the video flows well enough and carries the story,” he says.

That said, YouTube, while not always Horne’s priority, has enabled him to earn a living doing what he loves.

“As far as I’m aware, I was the first landscape photographer on Youtube. Back then, ‘vlogging’ wasn’t a thing (I greatly despise that word, by the way, it makes me die a little bit inside every time I say it. I’ve always said ‘video journal’ because it feels less sensationalized and attention-seeking, and far more genuine),” remarks Horne.

Authenticity and Prospects for Growth

As for the “cool” factor of film photography, Horne doesn’t care.

“Back in 2009, shooting film wasn’t cool. And I’m sure many would argue that it still isn’t cool, of which I would probably agree. But I’ve been doing uncool things all my life. Case in point, I’m an avid inline skater and have been skating for over 25 years now.”

Part of what makes Horne’s photography and video journals so appealing to his biggest supporters is that everything feels authentic, which is increasingly rare these days, especially on social media.

“I’ve always seen myself as the tortoise in the tortoise in the hare — albeit a tortoise on speed skates, but that’s beside the point. By remaining true to myself, none of this feels like work,” Horne says.

“It’s what I would do anyway, and that’s a recipe for long-term growth — and hopefully long-term success. Will my channel ever reach 100k subscribers? Probably not. But that’s fine with me. I’m here doing what I love, and it’s so amazing that other people enjoy it as well.”

The Freedom, Limitations, and Potential of Large-Format Analog Photography

While any photographic process includes some limitations, even when working with the latest and greatest digital cameras. Autofocus can be only so fast, the resolution only so high, and the dynamic range only so expansive. Lenses are, of course, the cause of many limitations concerning composition and the overall look of an image.

Analog photography is no different in that it also includes challenges a photographer must overcome or work around, although the limitations differ from digital photography.

“Large format is limiting indeed, but that’s also why it’s so incredibly rewarding. It’s human nature to have greater respect for the things we work the hardest for,” Horne says.

“It takes time to set up a large format camera, meter the scene, and expose a sheet of film — so reactionary photos aren’t often worth pursuing. Large format is better suited for contemplative photography where you identify a subject, craft a composition, and then wait for the light. This process reinforces a sense of calm when the light arrives — allowing me to absorb my surroundings and enjoy the moment rather than second-guessing my every decision. This results in a greater sense of satisfaction with my own work, with few if any regrets about the subject or the composition after the fact,” he continues.

He explains that other limitations include setting up the camera before sunrise — “you can’t see anything on the ground glass” — and taking photos in the wind.

Horne’s go-to aperture is f/45, so it’s easy to see how extremely long exposures, a narrow aperture, and the elements can be especially tricky. Even at f/45, the depth of field remains narrow, further complicating the photographic process, especially for landscape photography. He also notes that dynamic range is limited when working with transparency film, a topic that will come up again shortly.

“It sounds like a lot, but each of these limitations forces me to work harder while giving my work a sense of direction,” Horne says.

Dynamic Range and Light

Longtime viewers of Horne’s video journals will know that the topic of “reflected light” comes up quite frequently.

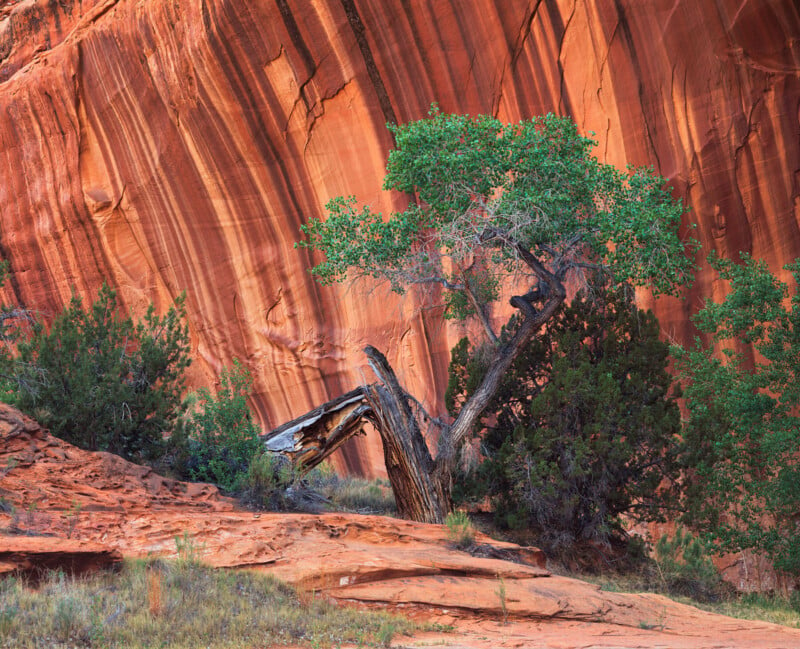

“Imagine being deep in a canyon where the sun is illuminating one sandstone wall, with the light from the sun-lit wall reflecting into the shadows of the opposing canyon wall. Not only is the light soft and warm, but it’s comprised of two colors, warm light from the wall, and blue light from the sky above. With two colors of light coming from different directions, any subject you photograph will have added depth and dimension,” Horne says.

Not only is reflected light beautiful, it’s also easier for transparency film to handle.

“When working with transparency film, the dynamic range is just over four stops — significantly less than today’s digital cameras. By comparison, black and white film and color negative film have a dynamic range that’s often greater than digital,” Horne explains.

He wonders how photographers would react if a digital camera were released with just four stops of dynamic range.

“Although this is certainly a limitation when working in harsh sunlight, there are types of light that actually look better when photographed with a lesser dynamic range, and reflected light is one such light,” Horne adds.

Transparency film “loves this sort of light,” Horne says, explaining that transparency film “captures the blue from the sky more than digital,” which gives subjects more dimensionality. With the limited dynamic range, a scene with relatively low contrast can appear to have stronger contrast.

“If one were to photograph the same scene on digital, it might feel a bit muddy because of the massive dynamic range, especially when combined with how digital minimizes the impact of the blue light reflected from the sky above,” Horne says.

Nailing Exposure

“With transparency film, both the shadows and the highlights are incredibly important. It’s a bit like taking a photo with a digital camera in JPEG mode where you can’t recover the shadows or save the highlights,” Horne says of the challenge of working with transparency film and achieving optimal exposure.

“What’s there is there. That being said, the highlights on transparency film are more forgiving than the shadows, which hold no detail whatsoever. And compared to digital, the highlights of transparency film will at least gracefully hold some pastel colors rather than falling off a cliff,” he adds.

Horne begins dialing in his exposure settings by metering a gray card using a Sekonic light meter in its spot metering mode. This often gives him a good starting place. He then sets the light meter to average mode and considers how bright and dark the subjects in the scene are.

“If I like what I see, I use that setting. Otherwise, I meter the brightest and darkest areas I hope to hold detail in, average them, then evaluate the brightness of each subject,” Horne explains.

“Learning to use a light meter represents the most significant learning curve of working with film — something that’s taken for granted when working with a modern digital camera where what you see is what you get,” he explains.

Of course, if a photographer botches an exposure on a digital camera, they know immediately and can adjust their settings accordingly. Horne has no way of knowing precisely what his photo will look like, although with his extensive experience, visualizing the results must help.

Favorite Film

“Fuji Provia 100F is a highly versatile transparency film. It has relatively low contrast and low saturation, which makes it quite forgiving. Some film stocks require additional exposure time for long exposures because of something called reciprocity failure. For example, a 30-second exposure at Velvia 50 requires 60 seconds of light to give an accurate exposure. Provia is a rockstar in this sense. It doesn’t require any correction until exposure times are measured well into the minutes. This is especially useful when doing exposures after dusk when the light levels are rapidly dropping,” Horne explains.

Unfortunately, during Horne’s time shooting film, the availability of particular film stocks has dwindled. Provia 100F is currently unavailable, for example, although Horne hopes that’s a temporary problem.

“I have a stockpile of Provia 100F in my freezer,” he adds.

However, there remains a constant threat that color transparency film, in general, may one day be unavailable altogether.

“If color transparency film were to disappear as a whole, I’m not sure what I would do. I love the process of working with film,” he says.

“There’s beauty in working with a mature technology and knowing that the image I produce today is the same quality as an image produced 10 years ago and 10 years from now,” Horne explains.

While that permanence in quality is an appealing aspect of film photography and gives the medium a timeless element, Horne is at the mercy of film manufacturers.

The Benefits of Large Format Analog Photography for Landscape Photographers

Large-format photography delivers impeccable image quality and sharpness.

“For me, the greatest advantage of large format — even greater than the impressive image quality — is that the camera slows me down and forces me to think more about what I’m photographing. Is this the best light? Is this the best composition? Should I photograph this subject another day when the conditions are better? There are no shortcuts, and I’m responsible for every step of the process,” Horne explains.

Because of being forced to be so much more meticulous, Horne has a “ridiculously high keeper rate.”

“It’s not uncommon for me to photograph 10 subjects on a nearly two-week trip, resulting in six or seven portfolio photos I’m completely satisfied with, without the need to crop the images or significantly alter them in Photoshop,” Horne says.

Even though Horne can carry only so much film, he doesn’t think this is prohibitive for making great photos.

“If you were to hand a digital photographer a memory card that can only take 36 photos, they would laugh at you. But if you hand that same photographer a 35mm film camera with a 36 exposure roll of film in it, they would likely have a tough time finishing that roll. When every photo counts, somehow it changes things,” he says.

“There is a profound sense of satisfaction that comes with exposing each sheet of large format film. It gives a sense of accomplishment that carries forward through the rest of the day. As such, there have been times when, while returning to my truck, I found an interesting subject — yet I had no desire to photograph it because of the sense of satisfaction from taking a photo earlier that morning,” Horne adds.

For a typical four-day backpacking trip, Horne goes into the field with food, camping gear, camera equipment, and enough film for eight photos. “I have more film than I need,” he says with inspiring confidence. He aims to return home with at least one image he’s happy with, but sometimes he’ll return with six or seven portfolio-quality shots.

A Large Format Camera Isn’t as Heavy as Expected

It’s easy to watch Horne schlep his gear in his video journals and imagine it’s back-breaking labor. However, he says that looks can be deceiving.

“Large format cameras look big and heavy — and don’t get me wrong, some of them can be — but they don’t have to be. My typical 8×10 kit probably weighs less than what many people reading this carry. My 8×10 camera, Chamonix Alpinist X, is made of carbon fiber and wood, the film holders are made of lightweight wood, and the lenses are very small and light (52mm filter size). I carry everything in a comfortable backpack designed for ultralight backpacking made by Zpacks. That backpack alone saves significant weight over a purpose-built photography backpack,” he says.

He doesn’t know the precise weight of his kit off the top of his head but says it’s light enough that he sometimes forgets he’s carrying it while scrambling up and over rocks.

Horne says that a pack with five days worth of food, his tent, sleeping bag, sleeping pad, cooking gear, jacket, 8×10 kit, video kit, and other miscellaneous items weighs just less than 34 pounds (15.4 kilograms). He’s preparing for his annual backpacking trip to southern Utah, which will undoubtedly produce incredible photos.

Location, Location, Location

Part of his high success rate is preparation and location scouting.

“Scouting is incredibly important, especially when venturing beyond the icons and discovering my own subjects. Toward the end of my trips, when most of my photography is done, I enjoy wandering without my camera just to see what I can find. By following my curiosity, I often discover interesting subjects or themes for a future visit. As an example, I found an interesting canyon in Death Valley toward the end of my 2022 visit. I made note of a particular glow of reflected light, then photographed that scene one year later when I returned to Death Valley. I often have a shot in mind when returning to a location, which makes it easier to get to work,” Horne tells PetaPixel. Sometimes an image really is a year in the making.

As for his favorite place to capture images, a question that stumps many photographers, Horne answers the question with ease.

“Without a doubt, Zion National Park. I first visited Zion as a kid on a family camping trip when I was 6 or 7 years old. It was summer, and I remember us hiking the emerald pools trail when a thunderstorm drifted over the canyon — its booming thunder echoing between the canyon walls as large raindrops began to fall. The sights, the smells, the scale. I’ve been obsessed with Zion ever since.”

“It’s not a large park compared to some, but there’s so much to explore, and it changes with every visit and every season. Perhaps it comes as no surprise that one of my favorite images is from Zion,” Horne says.

“It’s a quiet image taken during the fall in a maple grove, the entire scene bathed in subtle reflected light. Several boulders occupy the foreground among the grass and fallen leaves. Off in the distance, through a tunnel of maples, is a yellow maple against the base of a massive cliff. I love this photo because it captures the feeling of being there. By looking at this photo, I can sense the tangy scent of the maples in the breeze and feel the presence of the towering sandstone walls all around me. It transports me to a place I love, and that’s what I love about it,” Horne says of one of his all-time favorite images from his favorite location.

Reflecting on Horne’s Work and Words

Ben Horne proved as gracious with his time as he is talented behind the camera. Although many of PetaPixel’s readers likely shoot exclusively with digital cameras, offering numerous advantages over film cameras, analog photography remains alluring.

Large format photography sunk its claws into Horne, and its hold is unrelenting. He loves the entire process, from start to finish, and enjoys the challenges of analog photography. It has proven extremely rewarding for him, and his work has inspired others to follow suit.

While his results speak for themselves, and it’s by no means required to understand precisely how he created each image to enjoy Horne’s photography, there is something to be said for how he makes his images and shares his journey with viewers online.

His approach expertly combines yesteryear’s photographic equipment and technology with the reach only possible with the internet, a decidedly modern invention compared to 8×10 film cameras. The juxtaposition is fascinating and fantastic in equal measure.

More from Ben Horne

Ben Horne’s photography is available on his website and Instagram. His video journals are available on YouTube, and people can support his work on Patreon or by purchasing prints. Speaking from experience, his annual portfolio box sets are expertly-crafted and an excellent addition to any photography enthusiast’s collection.

Image credits: All images © Ben Horne