Can a Photograph Change the World?

Portraying injustices is not something novel. From the beginning of the twentieth century to the present day, many photographers have been concerned about leaving their mark. But can we try to change the world – even make it a better place – through a photograph?

“Photography is a small voice, at best, but sometimes one photograph, or a group of them, can lure our sense of awareness.” —W. Eugene Smith, Paris: Photopoche

From the World to Utopia

The term “documentary photography” refers to images made with the aim of reflecting the world, respecting facts, and seeking veracity. As such, documentary photography is an image that confirms and certifies an event and is based on its ability to bring reality closer. This does not mean that documentary photography shows the whole truth nor is it the only photographic possibility. On top of that, those photographs need to be disseminated and need an audience to be challenged by them.

Utopian documentary is an aspect of documentary photography, but it goes further. Photographs are not only taken to indicate something, to show reality, but they also rely on an image’s potential ability to convince, its powers of persuasion to improve the world.

How can a photograph have such an impact on us? On one hand, the mechanical component of photography (the camera) makes perceived facts more believable. On the other, photography is socially considered to be more accurate than other means of art. The photographer focuses on reality, obtaining an image that, by analogy with the portrayed subject, will be synonymous with veracity. Moreover, there is another idea that in order to capture said image, the photographer had to be an eyewitness – they had to be there.

The Beginnings of Documentary Photography

The first images produced with a camera were obtained nearly two centuries ago. From the very beginning, photography swayed between being documentary, getting closer to reality and representing facts, and being artistic, expressing feelings and building scenes. In other words, truth or beauty.

Documentary intention in photography, however, did not emerge until the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. It all began in New York, with Jacob August Riis (1849 – 1914) and Lewis Hine (1874-1940). Both photographed social themes with the ultimate aim of highlighting certain inequalities in order to change them. It is important to understand that during those years the transition to an industrialized society created massive inequalities.

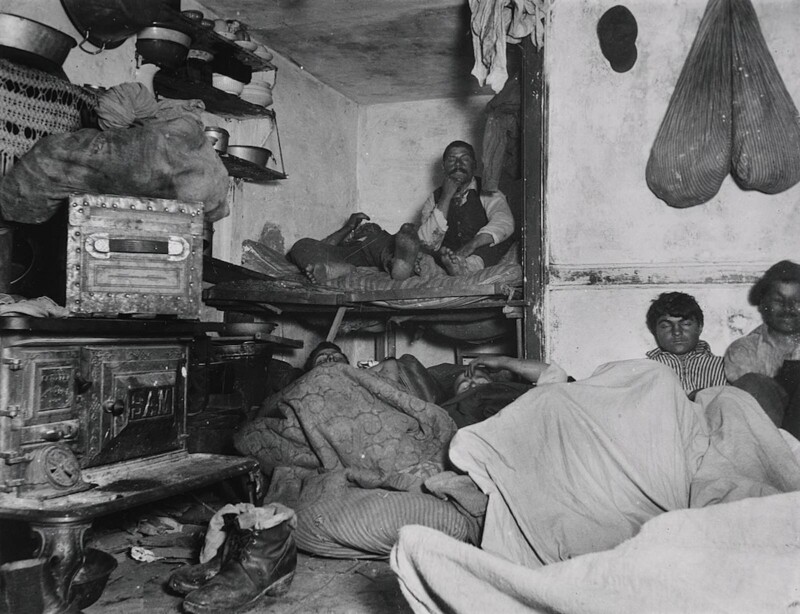

In 1890, Jacob A. Riis, an immigrant of Danish origin who was aware of the limits of the written word to describe facts, began taking photographs to show the vulnerability and living conditions of urban immigrants.

A few years later in New York he published How the Other Half Lives. The book was highly significant and led to urban reform in the city’s less favored areas, for example with the creation of playgrounds or gardens.

At the beginning of the twentieth century, Lewis Hine, the first sociologist to make himself “heard” with a camera, took photographs of immigrants arriving at Ellis Island, showing how they adapted to a new life. However, his most important works were on child labor in mines and textile factories. Thanks to these images he was able to promote the Child Labor Protection Act.

This intention of reform would be maintained in the 1930s, also in the US, through the Farm Security Administration – a set of reforms and subsidies approved during the Roosevelt administration with the aim of alleviating the suffering caused by the crash of 1929. In this program, a number of photographers were recruited to raise awareness among citizens, through images, of the need for such aid. Dorothea Lange, Walker Evans, and Margaret Bourke-White, among others, are worth noting.

From Documentary Photography to Photojournalism

After World War II, documentary photography lost some of its vigor. Photojournalism, however, took up its principles, and illustrated magazines, which were a booming success, published topics of human interest.

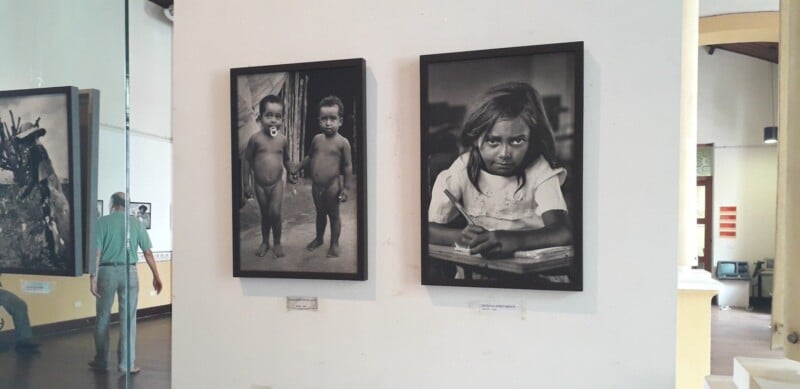

Sebastião Salgado (Brazil, 1944) was one of the noteworthy photographers at the end of the century. His main work focused on portraying the suffering of humans who experienced situations of exile, emigration, hard working conditions, or the misery of certain communities. It shows the Western world what life is like in places where our gazes do not fall. The Spaniard Gervasio Sánchez, with his long-term project Mined Lives, and James Nachtwey, with his work in Afghanistan, are notable contributors to this field.

Nowadays there are photographers with the same concerns who seek to persuade their contemporaries to change the world and mobilize consciences. Furthermore, it is already fully accepted that documentary photographs can offer many possibilities and that they are not governed by one specific formula.

Since the end of the twentieth century, the meaning of the word ‘documentary’ in photography has been evolving, although the same confidence in the communication capacity of photographs runs through every definition.

It could be said that documentaries that aim to improve and stimulate responses are still valid and relevant. There are still photographers who are interested in reforming and persuading their contemporaries of the need to make the world a better place and who still believe that documentary photography has to be committed to this goal. In short, they have not given up on utopia.

However, wherever there is a photographer, there must also be an audience that recognizes those images as documents and is able to read them, giving meaning to the images and acting accordingly.

Obviously, it will depend on each person and the life moment they are experiencing at that time. We will not all be affected in the same way. Nevertheless, as individuals, if we ultimately feel challenged by these photographs and we are moved, even just a little, we can do great good.

![]() About the author: Beatriz Guerrero González-Valerio is Professor of Photography and Aesthetics at CEU San Pablo University in Madrid, Spain. The opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author. This article was originally published at The Conversation and is being republished under a Creative Commons license.

About the author: Beatriz Guerrero González-Valerio is Professor of Photography and Aesthetics at CEU San Pablo University in Madrid, Spain. The opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author. This article was originally published at The Conversation and is being republished under a Creative Commons license.