Dora Maar: A Great Photographer Hidden Behind the Master of Painting

In the inevitable tide of recognition of so many women artists of the past 20th century who passed simply as muses, lovers, wives or companions, when their work was truly as strong, beautiful and original as that of their partner, Dora Maar, for many reasons, occupies a special place.

Maar Finds Photography

![]()

When the family returned to Paris, Maar studied painting and decorative arts before making the camera her means of livelihood and artistic expression. Fashion photography, unusual portraits – her output was so wide-ranging that in 1931, before she was even 25, Maar already had a successful studio alongside the set designer Pierre Kéfer.

Maar then opened a solo studio where she created some of her most famous and delirious photomontages. The best known is perhaps Ubu Roi (1936), the representation of a strange, non-human creature, a kind of armadillo fetus — she never wanted to indicate which animal it was so as not to lose its mystery — which André Breton considered a perfect example of objet trouvé (readymade).

Also 29 rue d’Astorg (1936) is a clear example of surrealist photography, in which elements of different size, location and reality are mixed, as is Star Mannequin (1936). Other photomontages of children and women lost in endless labyrinths or of bourgeois rooms invaded by mud and rain are also to her credit.

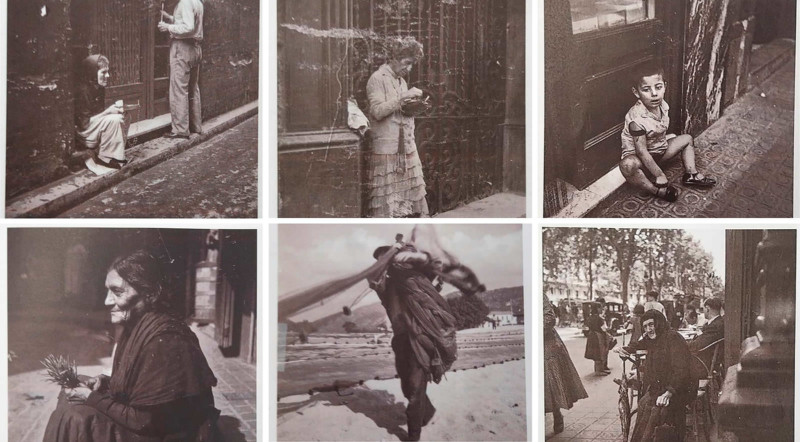

In the first half of the 1930s, Maar, like fellow photographers such as Henri Cartier-Bresson, alternated her depictions of the rich and famous, fashion and luxury, with depictions of the squalor and poverty that existed in Paris at the time. The difference between Maar’s photographs at that time and those of Brassai, Eugène Atget and others is that the objective or documentary aspect does not prevail in them, but rather a search for symbolism and freakishness that we would later find in the work of photographers such as Diane Arbus.

In 1932, Maar traveled to Barcelona and photographed street life in the city. She also took crude portraits of poor people.

Her work attracted the attention of the society of the time. She was soon invited to join the most advanced and modern circle in Paris: the surrealists. In this environment, she was a lover of the writer Georges Bataille, friend of Jacques Prévert and Paul Éluard, and a close friend of André Breton’s second wife, Jacqueline Lamba. In fact, Lamba and Breton probably met through Maar.

Surrealism freed Maar from the tyranny of appearances in photography and allowed her to express a wild spirit that mocked everything, including, and perhaps above all, her own fears.

Enter Picasso

Maar met Picasso in 1935, a year before the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War. In addition to her physical and intellectual splendour, the Malaga-born artist was undoubtedly attracted by the fact that she spoke perfect Spanish.

Married to Olga Jojlova and also paired with a young lover, Marie-Thérèse Walter, Picasso fell madly in love with Maar. She had caught his eye by playing at cutting herself with a knife in a café and the painter stole the bloody glove she was wearing at the time. This, no doubt, was the beginning of a relationship with dark omens.

When she became part of Picasso’s strange circle, his circus of valuable but submissive women, her career ventured down a dangerous path.

She spent eight years with Picasso. It was undoubtedly an extraordinary period for the artist, during which he painted many of his best works, including portraits of Maar. She performed an extraordinary act by photographically recording the constructive “process” of Guernica. This was totally innovative at the time, and would give rise to many other works by photographers such as Hans Namuth with Pollock, or Clouzot with Picasso himself, but Maar’s originality remains unrecognised.

Picasso also worked painting on negatives with Maar, but later insisted that she abandon photography to devote herself to painting – in his view the “great art”. At the end, Picasso led Maar into the terrain he absolutely dominated.

It must be said that she struggled to make personal pieces and some of her works, despite the influence of Picasso’s art, are interesting in their own (e.g. The Conversation, from 1937). But to compete in a terrain in which Picasso was the master was an almost impossible challenge.

In 1945 Maar produced still life paintings in the style of Picasso and later some portraits, mainly of women, reminiscent of other surrealist artists such as Leonor Fini.

As always with Picasso, it was a new love affair, this time with the young painter Françoise Gilot, that ended a relationship that had become extraordinarily toxic, with Maar bordering on madness and Picasso abusing her appallingly.

Third Act

Maar was confined to a mental hospital, received electroshocks and suffered the terrible psychological treatments of the time, which was as good for schizophrenia as it was for broken hearts or depression. Thanks to the poet Paul Éluard, who asked Picasso for help, Maar managed to leave the institution. She underwent therapy with Jacques Lacan, then went into seclusion, devoted herself to painting and sought relief in a Catholic mysticism. Thus her famous phrase was born: “After Picasso, only God.”

From the 1950s onwards her painting moved towards abstraction, albeit closely linked to landscapes, highly impastoed works that are a complete departure from Picasso’s art but not formally very interesting.

Maar’s tremendous emotional dependence on Picasso, the extreme aspect of her despair, meant that her figure, for a long time, was deprived of the brilliance that accompanied her early success and the complexity of her work.

Notable historians such as Mary Ann Caws and Victoria Combalía, who knew her personally, brought her out of anonymity with their writings. And little by little, exhibitions, such as the 2019 show at the Tate, have recovered her name and her legacy for the history of art. The third act is underway.

About the author: Amparo Serrano de Haro is an Associate Professor of Art History at UNED – Universidad Nacional de Educación a Distancia. The opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author. This article was originally published at The Conversation and is being republished under a Creative Commons license.