Navy Photographer Shoots Portraits of WWII Vets Before It’s Too Late

![]()

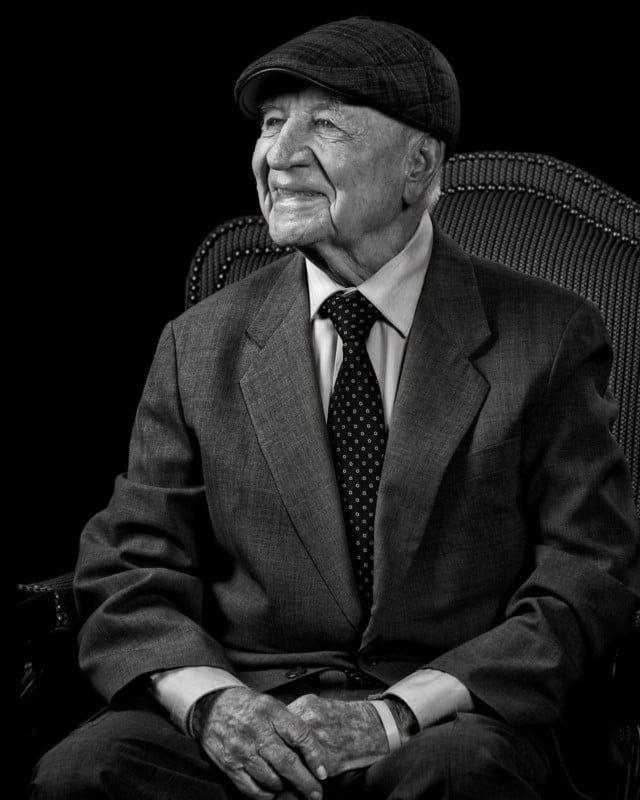

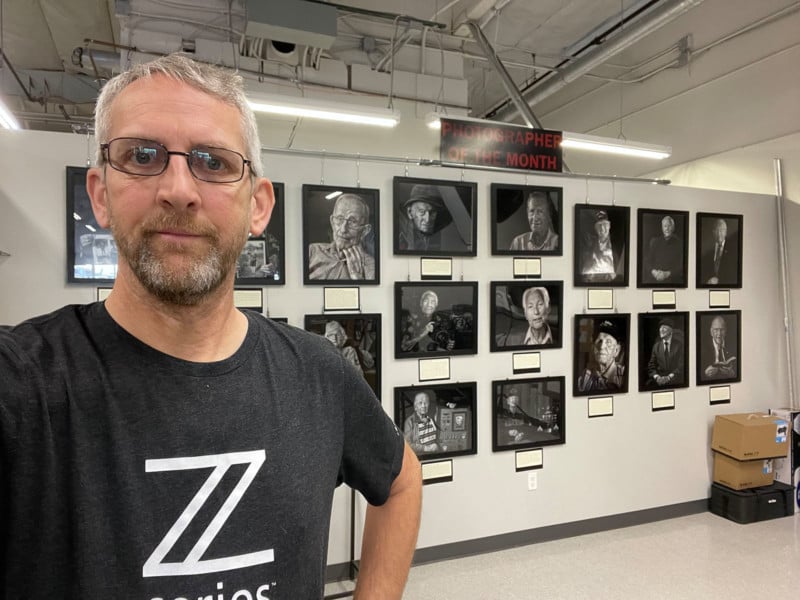

Navy photographer Mickey Strand, who served for 24 years before retiring in 2009, has captured portraits of more than 115 World War II veterans since 2017. Of those, only 10 to 15 are still with us today, which shows the urgency of moving forward before it’s too late.

Strand had previously captured portraits in the Navy, but his style was the standard flat lighting of a military headshot for almost everything until a mentor gave him some advice.

“This mentor tasked me with coming up with one portrait a week,” Strand tells PetaPixel. “He asked me to try new stuff and experiment with lighting and posing anything but the standards I had set for so many years.

“He also said I should find a subject that I was interested in, to talk with them and get to know them a bit. This way, I would be looking for a genuine portrait of the subject and not trying to make a photo but be taken by a moment.”

Strand started a general portrait project in 2016 but narrowed its focus to World War II veterans in 2017 after a visit, shoot, and exhibition at the Mount Miguel Covenant Village (an assisted living community) for Veterans Day in November of 2017.

Traveling for Portrait Shoots

The portraits have all so far been shot in California—a full day in Ventura, CA, four days at the California Veteran home in Los Angeles, and three days in the California Veteran home in Chula Vista.

One portrait of veteran Sgt. Wallace Chavkin, US Army, a pharmacy tech in Europe was shot in Palm Beach, Florida. Strand was speaking at a conference at the Palm Beach Photographic Center and a friend of a friend introduced him to the veteran’s daughter. The Center then let Strand use their studio.

“I hope to start traveling and shooting all over, but it comes down to funding,” explains the veteran Navy photographer. “I can find veterans and organizations to help locate vets, but it comes down to financing on the traveling side, so I work closer to home for now. But I’ll hop on a plane if the opportunity arises.”

Stories of Struggles, Sacrifice, and Camraderie

Stand says that his subjects are all heroes no matter where or how much they served. But he has met some very renowned military people. He has met a few POWs, many Flying Cross recipients, Purple Hearts, and then there is Cmdr. James Forester, a survivor of the USS Wasp (CV-7) sinking.

The photographer says he is blessed to learn about those who served and what they had to endure to get us to where we are today.

“We have not arrived, but we have come a long way,” reflects Strand. “I photographed Garland Cheeks, Steward’s Mate 1st Class, who served on the USS Menard (APA-201), an attack transport.

“Stewards like Garland prepared and served meals to the officers and maintained their quarters and uniforms. He recounted that he and the other stewards, “all Black”, had to stand while eating due to no table being provided for people of color.”

Joe Ray Gonzalez, Private First Class, recalled to Strand his first night in a foxhole on Okinawa and the companionship of his fellow Mexican service members “who all banded together” and helped him through this tough first night.

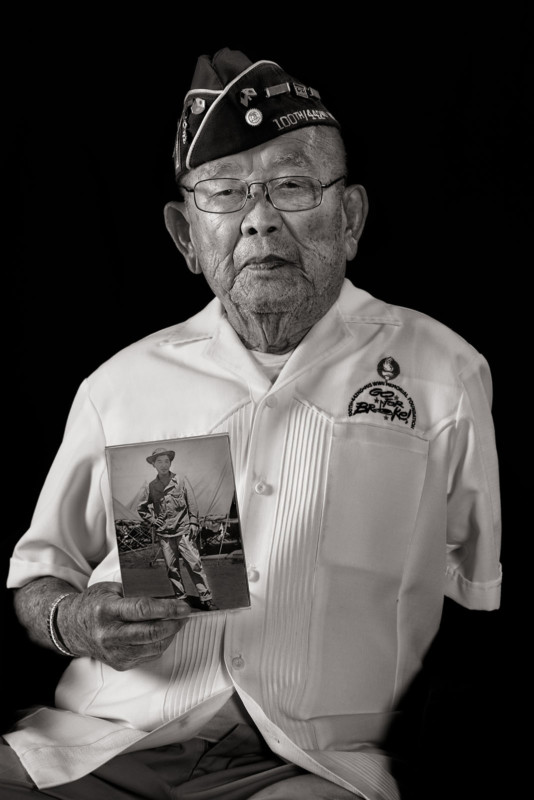

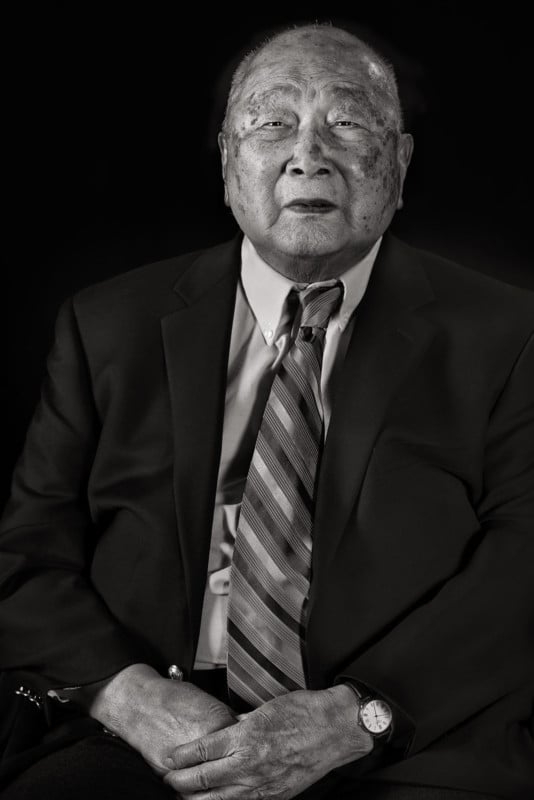

“I photographed Corporal Noboru Seki (Don), who served in the US Army with the 442nd Regimental Combat Team, L company, a segregated unit comprised of Japanese American service members,” recollects Strand.

“During a heavy machine-gun attack, Don lost his arm in the Vosges Mountains [France] while saving the surrounded 36th division from Texas. Veterans have been kinder and more selfless than their country has been to them.”

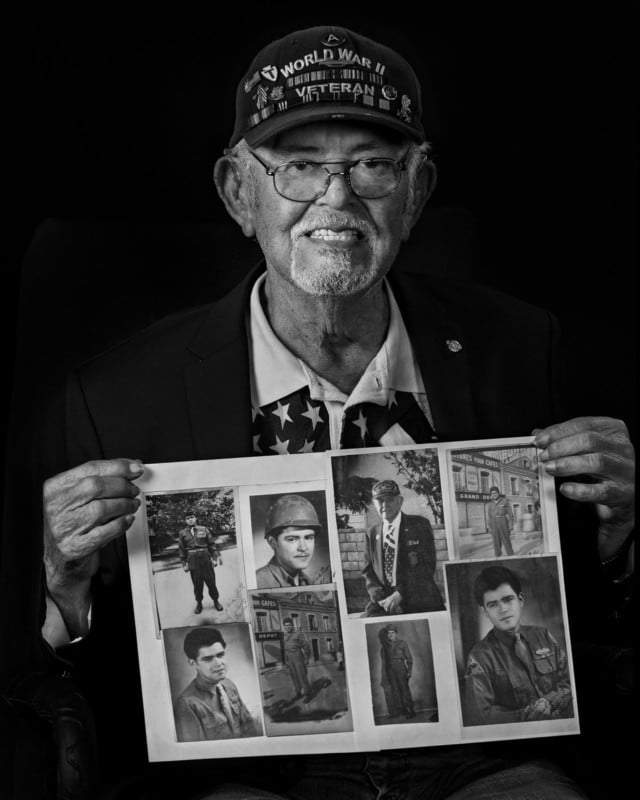

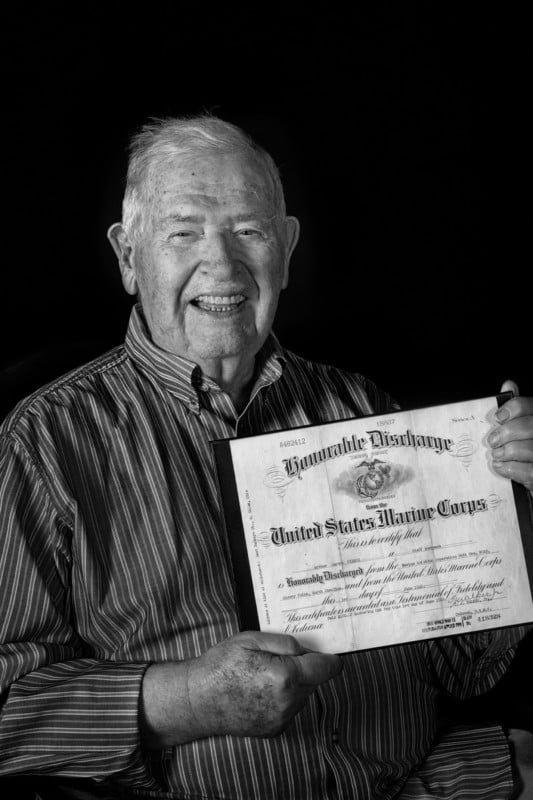

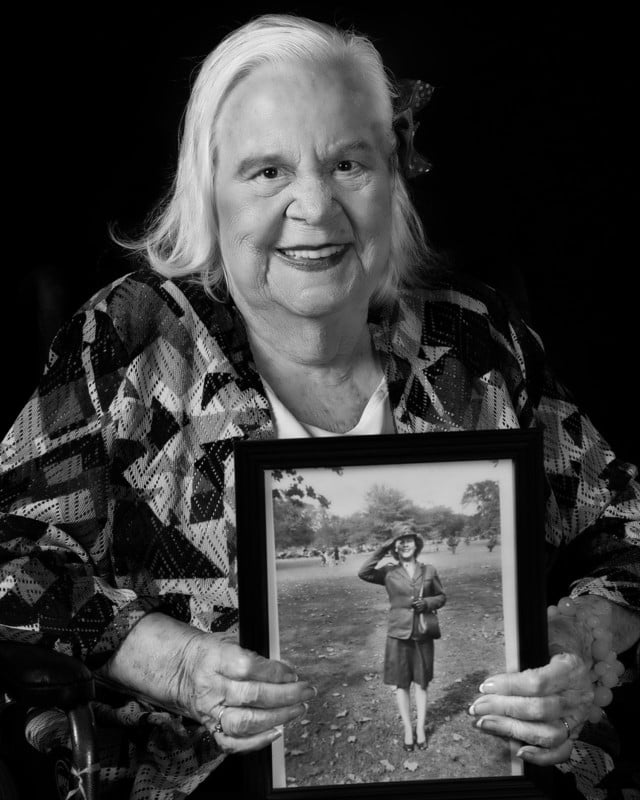

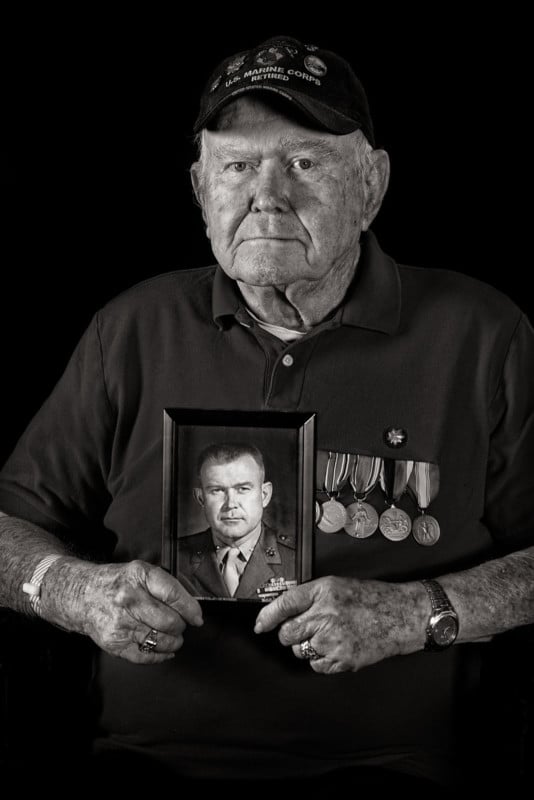

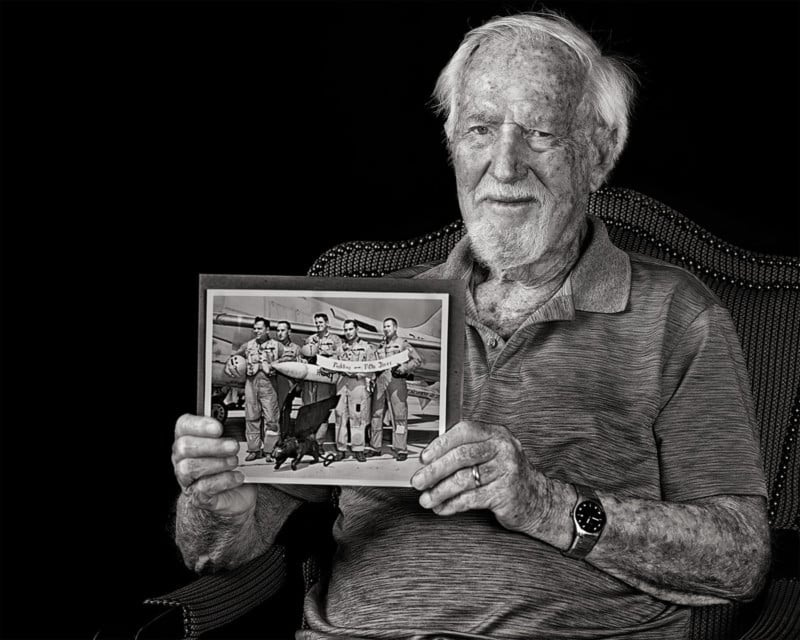

Some members who can still wear their uniforms often do to a session. Many bring in a photo from their service years, and it’s an opportunity for Strand to create then and now images. Other subjects pose with things that are meaningful to them, such as military photographer Joe Renteria posing with an assortment of cameras.

Joe Renteria served as Fleet Admiral William Halsey Jr.’s photographer throughout World War II and documented the atomic bomb tests. Strand maintained a friendship with him for years until he recently passed at 104.

Renteria was probably the most active 104-year-old Strand had ever met. He used to have lunch or coffee with him at least once a month when Renteria invited him to a veteran lunch group.

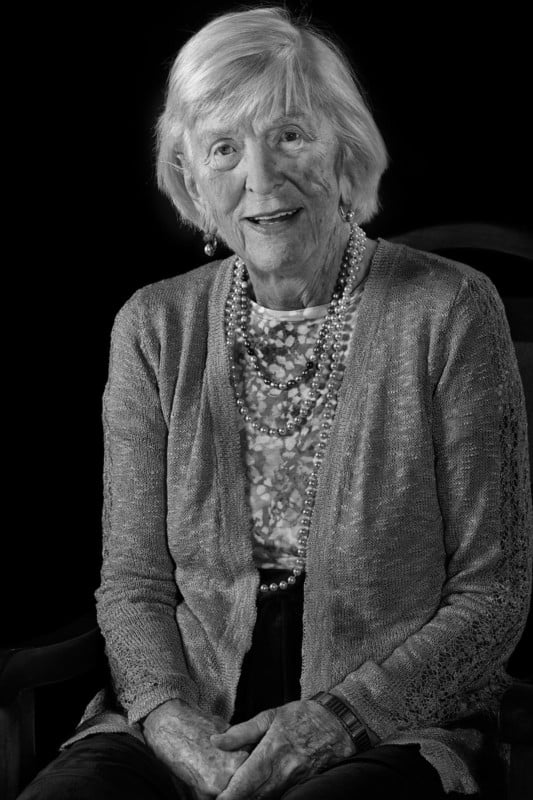

Strand loves it when vets show up and tell him stories. Of course, some of the neatest images have been in uniform, but he has photographed veterans in everything from dress uniforms to Hawaiian shirts.

The oldest subject who has sat in front of Strand’s camera thus far was one hundred and three years old. A few folks were 95 when they first posed in 2017, but they would be 100 today.

Strand has only been able to sit and collect ten portraits of World War II women veterans. He has four more from later service but says he would love to capture many more.

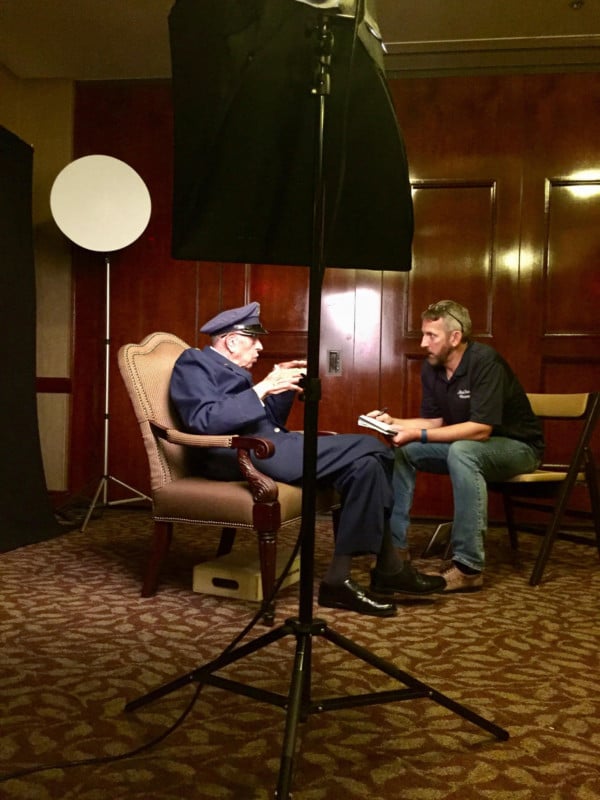

“I take really crappy notes,” confesses Strand. “I was having trouble with the caption write-ups early on, so I needed help. I got some guidance from some bloggers I know, and they suggested an interview reporters’ recorder. So, I got the Zoom H1n and did the next event. It was a simple, easy-to-use tool that was a game-changer.”

The audio recordings helped, and someone asked if Strand was shooting a video of the interviews. He had a spare camera and tripod, so he did the video recordings. But they are just to help him with taking notes. He listens to the interview while editing the member’s portrait as it puts him back to the chat he had that day. It helps him pull a better photograph from the data that his camera recorded as the member recalls a moment in their service. Sometimes he listens to them over and over again.

Capturing the Portraits

“I schedule a 2-hour block in the studio so that we are not rushed,” Strand says. “If I’m at the member’s home, the appointment is usually an hour. Most folks who can come to the studio share a story or two and their service info in about 20 min, and the portrait taking is usually 20-30 min.

“Still, some veterans love to chat, and I have shot some veterans with lots of memory, photos, or memorabilia for over an hour. But it’s a chat session with most veterans, and time flies by.”

Strand says he captures 100 to 200 images in a session. Initially, it started with 20 to 30, but “images are free these days” due to the transition from film photography to digital. He always captures the seated official image but tries not to restrict his shooting. He tries to let the veteran create an image specific to them. The photographer is prepared to be amazed by each person who blesses him by sitting down in front of his camera.

“I try to stay out of the way and let the subject chat,” says Strand. “Tell stores and gaff. There is a moment about half a second after someone laughs that their face is so happy, and their eyes open back up and relaxed; it’s magical.

“Some members need me to capture a somber, reflective moment. Sometimes when they remember a fallen friend. I am grateful when I find out I am the first person they have shared the story with. So, I try to be present and be ready.”

“I start on the tripod with a few standard poses,” explains the retired Navy shooter. “I set a good look with my Nikon Z7II and use a wireless remote, so I can still get shots from in front of the camera. But I invariable grab the camera and change over to another lens, currently loving the new 105mm [Nikon NIKKOR Z MC 105mm f/2.8 VR S], and start to let the portrait session take me into the subject.

Besides the Nikon 105mm, he also shoots with the Nikon NIKKOR Z 85mm f/1.8 S. He started the project with his Nikon D750 and then took hundreds of portraits with his Nikon D850. Strand found “that thing” to be a workhorse, but he loves the new mirrorless system.

Strand will shoot with any light as he has been through the gamut of lighting in the last six years. He started the project with a Calumet Travel (Bowens Gemini) light system with two 750W heads and a 500W. Then he tried LED with a second-hand Westcott Skylux 1000W three head system, which he still uses occasionally. He currently uses a Paul C. Buff DigiBee DB800 3 head system. He likes that the LED [400W equivalent] is daylight balanced for video or still shooting, and he has flash for when he wants that too, and it’s pretty affordable.

Strand was trained to fill the frame but does crop occasionally. He likes to print in 16×20,” and that is not the aspect ratio of the sensor/film. He is aware that all the images can be printed way bigger than he will be able to.

“The prints are all in B&W or chromatic greyscale because it speaks the loudest for this work,” says Strand. “But I was taught that to get the best B&W images, you have to start with the best color image. So, I edit the final print in color and then do my B&W conversion. Each client gets the B&W final image and sometimes the color image if it talks loud enough to me.”

A Career as a Navy Photographer

Strand’s father was an amateur photographer who had a basement darkroom in Racine, Wisconsin. He gave Strand his Minolta SR-T 101 when he got his new Minolta X-700. Strand helped his father shoot his aunt’s wedding when he was about 12. He worked with the high school yearbook staff, took photo classes, and was a newspaper staff member. These extracurricular events built a love for the craft.

He joined the Navy and was fortunate to work in the photo lab and have a photography career on his first ship.

“I joined the Navy for the chance for something new and exciting,” says Strand. “Travel and overseas adventure, to a kid who was not super and interested in going the traditional school route. I figured it gave me a chance to grow and learn, and being the oldest of eight kids, not a lot of college money was around. So, I made my way in life, just like my folks did.”

Strand says the Navy used everything from aerial reconnaissance cameras in pods on the belly of aircraft to medium format Bronicas & Mamiyas.

“But the everyday shooting workhorse of my days was the Canon F1,” says Strand. “I put too many rolls of film to count through one of these.

“The Navy moved to Nikon in the early days of digital with the joint Nikon Kodak DCS systems. My first touch of digital was an early DCS100. When we went full digital, the Nikon D1 had just come out and was a great replacement for film cameras, and used all the Nikon glass we had for the DCS systems. So, I have been Nikon from then on.”

Strand retired in 2009 after 24 years of active service as a Photographer’s Mate Chief Petty Officer. He was deployed many times from the ’80s to 2009 on many platforms, from aircraft carriers to missile cruisers, with navy, marine, and army personnel units, but he tries to Remember Everyone Deployed (RED). He says everyone served, and they can tell their stories to one another when they meet up.

The Future of the Project

Strand has no clue how many World War II veterans are still alive. If you served on active duty before September 2, 1945, and were 18 years old then, you would be 95 today. Strand has photographed a staggering number of veterans who served at 16 or 17, dropping out of high school to enlist, but that still makes them 93.

Many of the veterans he has worked with have lived into their 100s. It is incredible to think about these heroes who gave so much and lived extraordinary lives.

Strand does not know how long his project will extend into the future.

“I suppose sometimes I will run out of World War II veterans to photograph. I have worked on new sub-lines of the overall veteran’s portrait series with Korean war and Vietnam War Portraits, and I have done two small print shows for them. Maybe someday, the project will evolve into one of those veterans’ stories.”

You can see more of Mickey Strand’s work on his website, Instagram and a Google 360 Tour.

About the author: Phil Mistry is a photographer and teacher based in Atlanta, GA. He started one of the first digital camera classes in New York City at The International Center of Photography in the 90s. He was the director and teacher for Sony/Popular Photography magazine’s Digital Days Workshops. You can reach him here.

Image credits: All photos supplied by Mickey Strand.