Photographer Allison Stewart Explores the Construction of American Identity

![]()

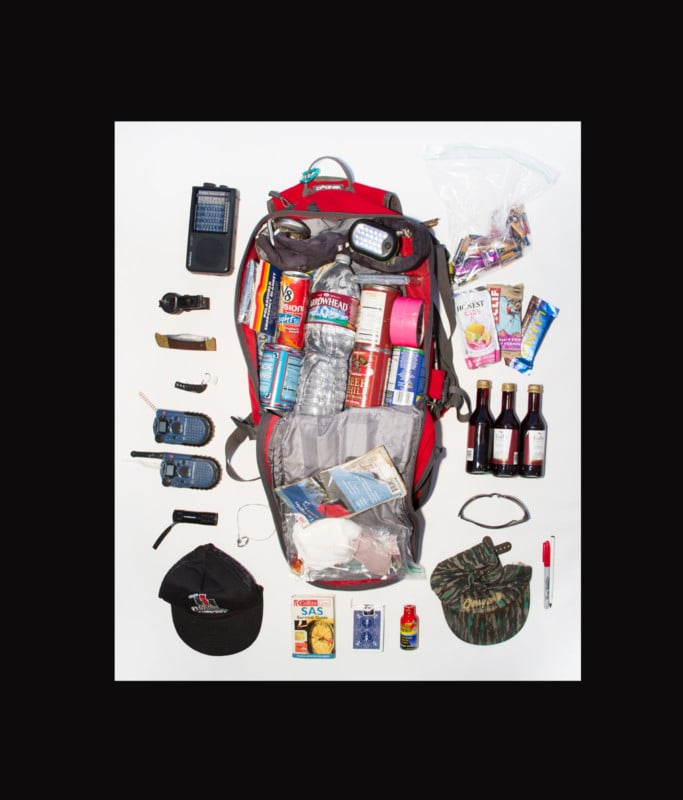

I was blown away when I first saw Allison Stewart’s series, Bug Out Bag: The Commodification of American Fear. The work zeroed in on the mindset, ubiquitous paranoia, or to borrow from Hunter S, Thompson, our collective “fear and loathing” of America today. Her photographs of ‘preppers’ and how they plan for the worst just seem so America 2021.

Allison is an American artist and photographer based in Los Angeles. Her work is published and exhibited internationally. Allison travels the United States exploring the construction of American identity through its relics, rituals, and mythologies. Her work, including the project Monuments (Removed), focuses on the archetype of the hero and the effects war has on our culture.

Her work has been published and exhibited internationally, including Cortona On The Move, the Aperture Foundation, The Wright Museum, The New Mexico History Museum, The Griffin Museum of Photography, The New Republic, Die Zeit, Wired, Mother Jones, and Vogue Italia. Wow – Vogue Italia.

Peter Levitan: I’d like to start with your powerful project Bug Out Bag. Frankly, I can’t think of a project that so closely mirrors the state of American headspace today. As you say on your website, “A Bug Out Bag contains the essentials needed to sustain life for 72 hours, or to possibly begin a new civilization.” Where did this idea come from?

Allison Stewart: The bug out bag came into being during the Korean War. Soldiers would keep a bag packed, ready to “bug out” at a moment’s notice. Preppers adopted the bug out bag concept and it has become a standard for basic disaster preparation.

A human can survive without water for 72 hours so most BOBs are designed to contain everything you need to survive for that amount of time, assuming you will be able to get back into your house or get assistance before 72 hours is up.

There are also INCH (I’m Never Coming Home) bags, which are more apocalyptic in their outlook and assume that society will need to be completely rebuilt.

How did you manage the project, where did you go and how long did it take? How do you find the people to photograph?

I started in 2014 by photographing people I knew who had gotten into prepping, then I went to Craigslist. I was lucky enough to get some press and that is when people began contacting me. People emailed me from all over the country so that was when I decided to make sure the project represented all of the different regions of the country. As I traveled and talked to people about my project people would tell me “I know someone you should meet” so I met people that way too.

All of my projects take several years to develop. I am usually following a rabbit hole I know very little about. I had the idea for the flat lay composition early on and so I stayed with that as a ”rule” for the project. I stopped photographing in 2016 when I had photographed every region of the country.

Did you photograph the Bug Out Bag “studio shots” on location? How did you do that?

Everything was shot on location. I never knew what the situation was going to be and since many preppers were wary of me, I wanted to keep my gear as minimal as possible.

My kit was a white backdrop, reflectors, and a Gary Fong diffuser on my speedlight. I would borrow a ladder, step stool, or chair to shoot from. Often when I was traveling, I would pick up packs of white poster board and build a reflector “box” around the unpacked bag.

The lighting situations were always a challenge. I shot in an off-grid trailer with one naked bulb, a library study room with flickering fluorescents, a carport in the blazing Georgia sun. I began to regret the day I decided on the pure white background, but the challenge helped build my editing skills so I can’t complain.

How have you shown this work?

The work has been shown in galleries and museum spaces as well as in magazines and online media. It was a featured exhibition in the 2018 Cortona On the Move photo festival in Italy where the photos were installed in a 16th Century Medici fortress. As an artist, it is rare that you have the opportunity to show your work in the “perfect” location for the project so I am very thankful for the curatorial vision of Arianna Rinaldo and Antonio Carloni.

Do you consider how you will show the work, as in a gallery show, book, or website before starting a project?

Those ideas usually develop as I am working on a project. I have always loved making books so I think a lot about how the project will translate into book form. I worked in art galleries for several years while I was in college so I also like to consider how my photographs will work on the walls and how that will frame the conversation.

I am always intrigued by the serendipity of how I find new photographers. I found the Bug Out Bag work on the winner’s page of the annual PX3 Prix De La Photographie Paris award website. Do you often enter award shows? If so, why?

I don’t enter award contests very often. It depends on who the jurors are. Photo competitions have always been a big part of the Photography world, but it is not something common to other areas of the art world. Competitions like PX3 are great ways to get your work seen by industry professionals you don’t normally have access to. I am always looking for ways to get my work out there in the world, and you never know what opportunities will come from them, like this interview!

Your work, which has spanned the removal of American monuments to Civil War reenactors, delivers what I would call social commentary on the evolving American identity. Is this a correct way to describe your vision?

I might have to steal that phrase for my artist statement! That is a great description. I began focusing on the archetype of the hero during the Iraq and Afghanistan wars and how the soldier has become a sacred secular Christ figure in the United States. As our country became more divided and I heard the phrase “real Americans” more and more I focused my attention on our American identity and how that has been affected by our culture of guns and romanticization of war.

If you had to define your territory, do you consider yourself a documentary photographer?

My work is documentary, but I am not a photojournalist. I spend years on a subject and do a lot of research in an effort to understand what it is I am photographing. I edit my work for color and contrast, but I never add or delete anything from a photo. I have always been drawn to documentary work and the power it has to create social change.

Is having a body of work, a series, important to delivering your message?

It is definitely the way that I work. It takes me a while to make sense of what I am photographing and what the message I am delivering actually is. Because of the subject matter, I am very careful of my visual language and that takes time to develop.

How do you know when a series is complete?

I’m never sure but once I stop shooting for a series I rarely go back. It usually happens because I have started working on a new project and my focus has shifted to the new work. There is always about a year where I am working on both projects and I feel like I am cheating on my old project with the new one.

I don’t know if it is possible to truly know when a series is complete unless the parameters are set up at the beginning, like in my photographs of the civil war reenactors. I photographed them during the sesquicentennial, so as soon as the “war” was over, so was my project.

Since your work requires travel, what equipment do you use? Or better stated for you, what is in your photo bag?

I am a minimalist. I carry as little as possible so I can travel easily, blend in with my surroundings, and climb a tree if I need to. It all has to fit on my back, otherwise it’s staying in the studio. I use my dad’s old Tamrac backpack that I have carried for years.

I shoot with a Canon 5D Mark III or my Sony a6000. My Canon 24-70 lens was my favorite lens to use for the BOB project but I have recently been shooting with a 35mm prime lens. I like how prime lenses force me to move and become part of the space I am photographing rather than an observer zooming in from a static point.

I carry a variety of filters and I always have a reflector on hand so I am prepared for any type of lighting situation I encounter. When I am traveling, I don’t always have the opportunity to come back to a site at a different time of day. I always research the locations and the lighting situation beforehand so I am prepared but Mother Nature has her own ideas about light so I have to respect that and work with what I have when I am there. Sometimes that can be very serendipitous.

I was traveling by train a couple of years ago and arrived in Kansas City just as the sun was starting to set instead of 9 AM as scheduled. I was able to photograph the Pioneer Mother Memorial statue in Penn Valley Park right at sunset and it is a far more beautiful photograph than I would have gotten at 9am.

What role has having an MFA had you in your career?

MFA programs help students develop a strong studio practice and create a well-developed body of work that they can begin promoting and marketing on graduation. I spent a lot of time really diving deep into the meaning of my work and the constant dialogue with professors and classmates allowed me to see how my work was being read by others. I have always had an active studio practice, but my MFA program really took that to a higher level and prepared me for public response to my work.

What are you working on now? How do you make that decision?

My projects always come to me while I am working on other projects. It is an organic process for me. Whenever I look back at older photographs, mostly taken for curiosity’s sake or just for the love of making a photograph, I always find the “seeds” of my projects.

I recently found a photo on my phone that I had taken of my brother’s coffee table, two years before I started the Bug Out Bag project. My brother was in the army for 17 years and now trains federal security guards. His coffee table was white and on top of it was a gun he was in the process of cleaning, cigarettes, and an overflowing ashtray. I remember thinking it was the perfect portrait of him so I took a photo of it from a bird’s eye view. Looking at it now I see that it was the seed for the look of the Bug Out Bag photos.

For the past decade, I have been looking at the archetype of the hero, mostly in relation to the soldier. My most recent project was photographing the removed monuments as part of that conversation. As I was researching Monuments, I learned that of the estimated 5,193 public statues depicting historic figures only 394 are of women, and none of the 44 memorials maintained by the National Parks Service are of historical women in history.

Most of the monuments we see of women are symbolic representations of motherhood, not actual women. I started looking at the archetypes of women and found myself very interested in the archetype of the witch. So, I am currently photographing people who identify as witches and their culture.

Last question… who are your favorite established or emerging photographers?

I am drawn to photographs with a strong social message. Nick Ut’s photograph Napalm Girl had a huge impact on me as a child and I credit that experience with why I am a photographer today.

August Sander’s inspiring and ambitious project People of the Twentieth Century has become an important archive that is haunting to look at now, Mary Ellen Mark’s incredible humanity and respect for the people she photographed has taught me a lot about my role and my responsibility as a photographer. And of course, Robert Frank’s epic journey through America to create The Americans was a great influence on me.

There is a lot of really exciting work being made right now by emerging photographers. I really love Jon Henry’s heart-breaking project Stranger Fruit, Genevieve Gaignard’s exploration of race and class, and Alayna N. Pernell’s series Our Mothers’ Gardens is a powerful critique of the gaze in photography.

There is a lot of powerful work out there right now. It is exciting to see!

You can find more of Allison’s work on her website and on Instagram.

About the author: Peter Levitan began life as a professional photographer in San Francisco. He moved into a global advertising and Internet start-up career. Peter photographs people around the world using a portable studio. This is his excuse to travel and meet people.