Irving Penn’s Timeless Photography and ‘Photographism’

![]()

When you mention Irving Penn, the first images that may come to mind are his fashion photography and mostly his 165 Vogue covers. He also photographed everyday objects, even detritus from New York streets like cigarette butts, leaves, and even chewed gum. This was described by former Director of the Art Institute of Chicago James Wood as ‘the cosmos underfoot.’

Penn had a manila envelope labeled with the word. This was the studio’s working folder into which went rough sketches, notes, and scraps of paper with ideas. Later on, there were also posters kept along with the folder.

“Penn left us with not so much a road map, but enough material as a jumping-off point to consider for an exhibition,” says Vasilios Zatse, deputy director of the Irving Penn Foundation, who previously worked in Penn’s studio.

“Spanning from 1939 to the early 2000s, the works in this exhibition will be accompanied by rarely seen archival materials and preparatory sketches, which articulate Irving Penn’s notion of ‘photographism’,” says Pace Gallery in introducing the show.

“Photographism” was never adequately explained by the photographer in his lifetime, and maybe it is a perfect tribute to take a look at it now.

The exhibition shows 30 photographs displaying Penn’s groundbreaking photographic style. Penn was trained as a painter but began shooting for Vogue and other high fashion magazines in the 1940s. Penn extracted ideas from multiple sources, including fine arts, drawing, painting, sculpture, and the more commercial graphic arts, such as typography and graphic design.

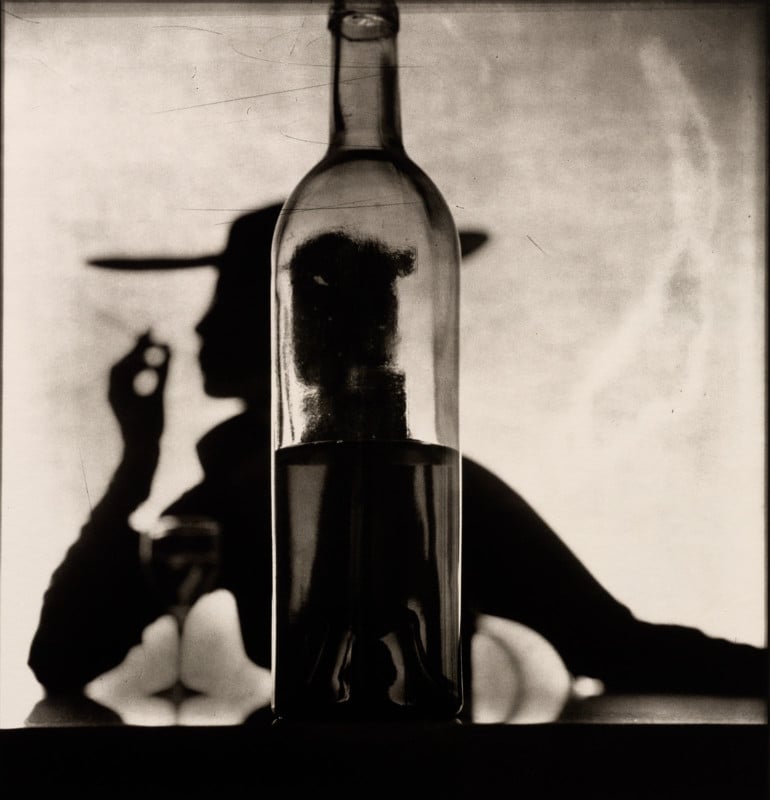

Penn sought a “simplification that I need in a picture” that really relates more to old painting and old sculpture.” And you can see that in Penn’s self-reflexive works, such as Bedside Lamp (2006) and Girl Behind Bottle (Jean Patchett) (1949).

Before he handled the camera, Penn would often conceptualize the final photo in a sketch. This would help him to hone in on the critical aspects of the photograph. These rough sketches were inspired not just by painting but also by sculpture, architecture, dance, and the Surrealism movement. Maybe that is what “Photographism” is—combining all of these art forms melding into the final photograph.

His first love, which was painting, was always there in his sub-conscious, along with other fine arts. In 1985, Penn printed a final portrait of painter Picasso which looked more like a test strip. He further added, “splatters of platinum sensitizer to give the fragment a bold, painterly reinterpretation.”

“What I yearn for as a photographer is someone who will connect the work of photographers to that of sculptors and painters of the past,” he said in 1975.

Penn was born to a Russian Jewish family in Plainfield, New Jersey, in 1917. He attended Abraham Lincoln High School in Brooklyn, where he studied graphic design with the famous Leon Friend, who also taught Jay Maisel. Penn attended the Philadelphia Museum School of Industrial Art (now the University of the Arts) from 1934 to 1938. He studied drawing, painting, graphics, and industrial arts under the famous art-director Alexey Brodovitch.

According to Anna Wintour, the editor-in-chief of Vogue, a magazine for which Penn worked for more than 65 years, he “changed the way people saw the world and our perception of what is beautiful.”

Vogue, in the 40s, was a place where experimental photography could be shown. And Penn was experimental throughout his career. He captured Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s unique image from a low angle with what seems like a wide-angle lens.

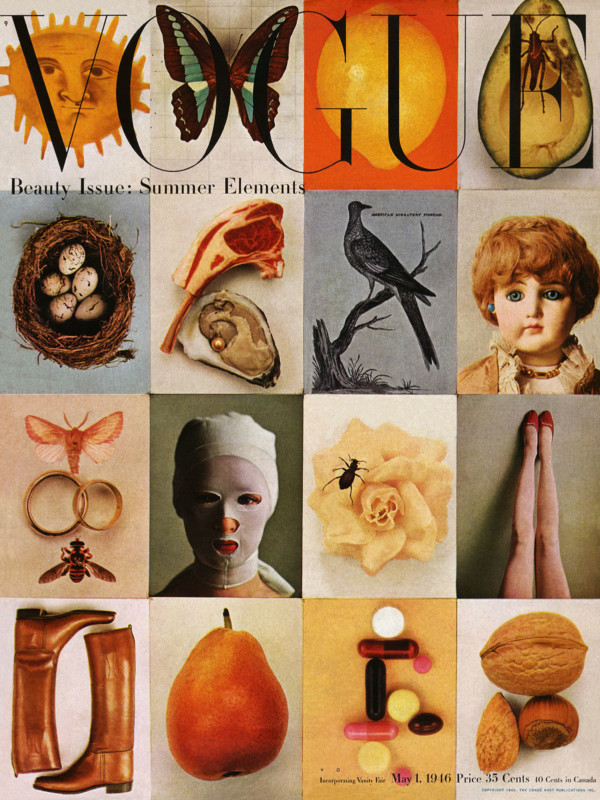

The exhibition showcases, among others, a Vogue cover from 1946, Beauty Issue, Summer Elements. It has sixteen photos just like an Instagram grid and shows the oncoming boom in retail after an era of rationing during the war years. Women were beginning to think about fashionable products and fashion itself.

There is Girl Behind Bottle, where Penn combines in a mysterious way his love for found objects to frame a portrait of a lady smoking behind a bottle. The B&W image creates three-dimensionality from a flat medium by having the model sharp in the bottle through its refractive powers, whereas the part of the image outside is soft in focus. The black scratches on the background and the available light exposure give it just the right amount of casualness to a posed studio setting.

The photograph of Eye in Keyhole creates the illusion that the camera is looking back at the photographer. Penn also interestingly places a second keyhole in the eye where the pupil should have been.

Gingko Leaves is Penn’s perfectly typical still life. He had picked up this green and yellow foliage from New York’s streets and arranged it in a formal pattern. He then printed it with a dye-transfer process which produced deep color saturation and permanence compared to C prints.

Mouth (for L’Oréal) shot in 1986 blurred the boundaries between advertising and art. This advertising image for L’Oreal cosmetics likens a model’s lips to a painter’s palette—offering an enticing twist on conventional representations of beauty.

Penn was walking past a junk shop in the 40s when he spotted a brass lamp on the sidewalk and immediately picked it up. It remained with him for the rest of his life. ‘For all those years, I turned my head, and the lamp was there. That’s my lamp. This picture is a love letter,’ said Penn.

He photographed Bedside Lamp on a plain white background, a technique which he pioneered early on to avoid distractions. It is no longer a lamp in the photo, but its shade resembles a flower jutting into the frame to show off all its colors.

Penn was a working photographer until the end of his life. He died on October 7, 2009. His final credit in Vogue was in the August 2009 issue. And even in his 90s, he worked half of the week.

“It was never clearly defined what he [Penn] meant by Photographism,” says Vasilios Zatse, who started working for Penn in 1996. “I like to think of it as Penn’s visual signature, the flavor of his work, his aesthetic. He wasn’t one to speak at length about his work in terms of trying to describe it. He let the work speak for itself.”

About the author: Phil Mistry is a photographer and teacher based in Atlanta, GA. He started one of the first digital camera classes in New York City at The International Center of Photography in the 90s. He was the director and teacher for Sony/Popular Photography magazine’s Digital Days Workshops. You can reach him via email here.

Image credits: All photos by Pace Gallery and Irving Penn Foundation and used with permission.