Bill Biggart: The Hero Photographer Who Died Capturing 9/11

![]()

September 11, 2001, was a sunny Tuesday morning. Bill Biggart and his wife Wendy Doremus were walking their dogs in downtown Manhattan. At about 8:45 a.m., the couple noticed clouds of grey smoke forming against the clear blue New York City skyline. A passing taxi driver informed the couple that an airplane had crashed into the World Trade Center.

The $3,000, 3.1-megapixel prosumer D30 had just been released in 2000 and was Biggart’s first DSLR. His EOS-1N 35mm SLRs were among the last professional film cameras that Canon would make but Biggart had been turning out important news images with them since the mid-1990s (and shooting in general since the 1970s).

Biggart began his two-mile, twenty-block trek toward the destruction from which everyone around him was fleeing. He shot film and digital images, cameras swinging from his shoulders, as he approached the unfolding scene.

For years, Biggart denounced color and then digital photography, working exclusively in B&W 35mm. Eventually, he saw that the news was going digital so he took up the new technology and switched to color film to match.

At 9:03 a.m., while still en route, Biggart observed a commercial airplane slamming into the South Tower. He lifted the D30 to his eye. Likely with his 80-200mm lens, he captured a brilliant orange and red fireball exploding out of the second tower.

With a press pass around his neck and a camera bag over his shoulder, in the middle of a crossfire – Bill was in heaven. —Wendy Doremus

Bill Biggart had moved to New York City in the early 1970s when the World Trade Center opened. He witnessed its construction and now he watched as the South Tower burned like a torch.

This was the moment when the same poignant thought crossed the minds of all Americans who were tuned into television news that day. Two plane crashes in the same spot, on the same day — this couldn’t have been an accident. But Biggart knew that whatever was going on, it needed to be photographed.

Biggart drew closer and closer until his shots of the towers were near fully vertical. Emergency rescue workers and even other photojournalists cautioned that he was getting too close. At 9:59 a.m., Biggart captured the South Tower disintegrating as it came crashing down, blanketing him and his Canons in dust and debris. Shrugging it off, he continued to shoot, taking several frames of the North Tower still standing, amidst the remains of the South. Then he began documenting the efforts of rescue workers, ignoring the smoking North Tower.

Being that the D30 was a crop sensor body which multiplied the length of the lenses mounted to it, Biggart seems to have primarily used digital for long shots such as the towers themselves and film for closer/wider shots such as people. He seems to have covered everything before him with all three bodies though, probably using a 50mm and two zoom lenses. Basically, he shot with everything he had available, in every way he could.

Biggart photographed rescue workers and victims coated in grey-brown dust. Yellow reflective stripes of firefighters’ clothing and red emergency lights pierce foggy scenes of disorder. A well-clad man striding through a field of strewn office papers, fractured drywall, and miscellaneous pulverized material. People with ashen faces gasping for air through dirty towels. Strangers helping strangers. Arms around shoulders. Coughing. Crying.

Most of Biggart’s shots were, of course, thoughtfully composed and carefully timed. Others, I’d argue, appear to be made more frantically, yielding evidence that even this hard-nosed, road-worn news vet had been shaken.

Then Biggart’s flip-phone rang. It was his wife, Wendy.

“I’m safe, I’m with the firemen,” he comforted her.

Bill said that he would meet Wendy at his studio in about twenty minutes. At this point, we can speculate that Biggart concluded that the height of the action was over and that he needed to process his film and dump his cards in prep for the immediate media release of the images.

But the twenty minutes in which Biggart planned to meet his wife passed. He was still shooting.

Biggart seems to have been in search of the hero shot to wrap with. The intrepid photographer began snapping some wide shots of the demolished South Tower, presumably with his back towards the North Tower.

Bolivar Arellano, a shooter for the New York Post who was also covering the terrible event, witnessed colleague Bill Biggart on the scene. Arellano stated that Biggart was closer to the towers than any other photographer, and in fact, closer than many firefighters.

Bill Biggart was vocal about his love for New York City. He often commented that it was the greatest city on earth. And his commitment to the city was evident with every shutter cycle that Tuesday morning.

At 10:28:22 am, the weakened support finally gave out beneath the impact zone of the North Tower, and the massive structure began imploding.

At 10:28:24 Bill Biggart took a beautiful photo of the ruins of the South Tower and the still-standing base of the North Tower. The scene was a tapestry of repetitive industrial lines fractured and softened by dust and smoke. The image is nearly colorless and muted, solemn and grim as the day.

Bill was probably still looking through the viewfinder of his Canon D30 when 500,000 tons of glass, concrete, and steel suddenly came crashing down on him at 120 miles per hour.

Wendy waited at the studio. And waited. She spent desperate but hopeful days searching overwhelmed hospitals for her husband. Fellow photographers shared their accounts of where they last saw Biggart.

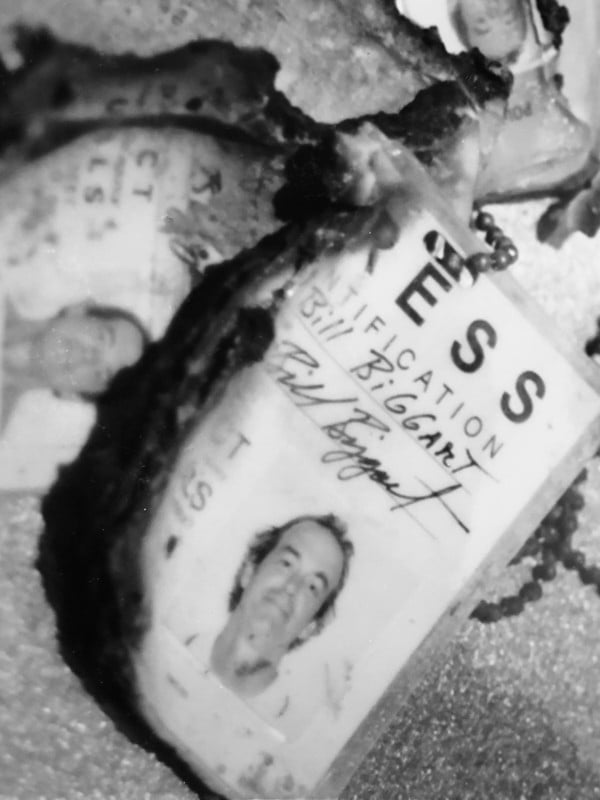

Four days after the tragedy, rescue crews were finally able to remove Biggart’s body from beneath the dense rubble that once comprised the World Trade Center. Biggart was the only professional photographer who covered 9/11 and did not make it out alive. But his images were possibly the most personal.

A friend and colleague, photographer Chip East was tasked with recovering any images from Biggart’s belongings. The lens elements had been sheared off or blasted out of all three Canon bodies. The film compartment doors had been ripped off both EOS-1N film bodies, exposing two complete rolls within them to bare light and erasing Biggart’s last film shots. The metal cassettes holding the other four rolls of film had been badly deformed which also admitted light, scarring many images with light leaks.

Of the approximate 144 possible film images Biggart may have taken, only a handful survived. The compact flash card within the D30, however, was cradled safely inside the camera’s magnesium alloy body. When Chip East first inserted the card into his reader, nothing happened. He rebooted his computer and miraculously, the card fired up and yielded its precious contents; 154 complete files, with accurate timestamps.

Biggart’s final photograph, the one taken at 10:28:24 capturing the remains of the South Tower, was featured in countless publications and exhibited at the International Center of Photography in New York City, then at the National Museum of American History in 2002. Bill Biggart’s equipment and belongings were also on display there and in 2008 at the Newseum in Washington DC.

Biggart’s 35mm film images are mostly damaged by light and heat. They are discolored and feature large, chaotic blotches, which, themselves are physical imprints of the destruction of the Twin Towers. Today, the film images exist as a kind of forensic artwork, expressing an incredibly unique and meaningful account of the disaster.

As a young photography student, I was fortunate enough to catch a glimpse of Bill Biggart’s work and personal effects during one of his posthumous exhibits. I took my photos on Kodak BW400CN with my Pentax K1000 and 40-80mm lens. I recently dug those photos out of my archive for this article on the 19th anniversary of the September 11th attacks.

I will never forget.

You can see Bill’s photos of 9/11 and his B&W 35mm photo essays on his website.

About the author: Johnny Martyr is an East Coast film photographer. The opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author. After an adventurous 20 year photographic journey, he now shoots exclusively on B&W 35mm film that he painstakingly hand-processes and digitizes. Choosing to work with only a select few clients per annum, Martyr’s uncommonly personalized process ensures unsurpassed quality as well as stylish, natural & timeless imagery that will endure for decades. You can find more of his work on his website, Flickr, Facebook, and Instagram.

Image credits: Photographs by Johnny Martyr. Please contact Martyr for use.