How Ansel Adams Revolutionized Landscape Photography

Billions of photos are being snapped and shared on the Internet every day. There are more cameras than people in the world nowadays. Photography is something we take for granted; something we can easily do whenever we want. But it wasn’t always like this.

He realizes the camera is not going to capture what he is feeling at that moment; how he visualizes the shot.

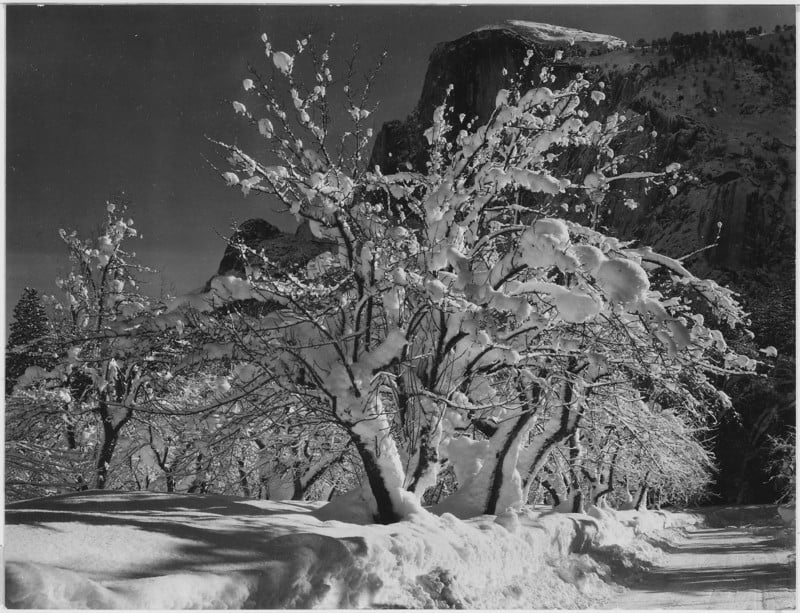

With the last plate in his hands, he makes a decision. He uses a filter to capture the Half Dome and when he later develops his photographs, he is hooked. He knows photography is something he wants to do for the rest of his life.

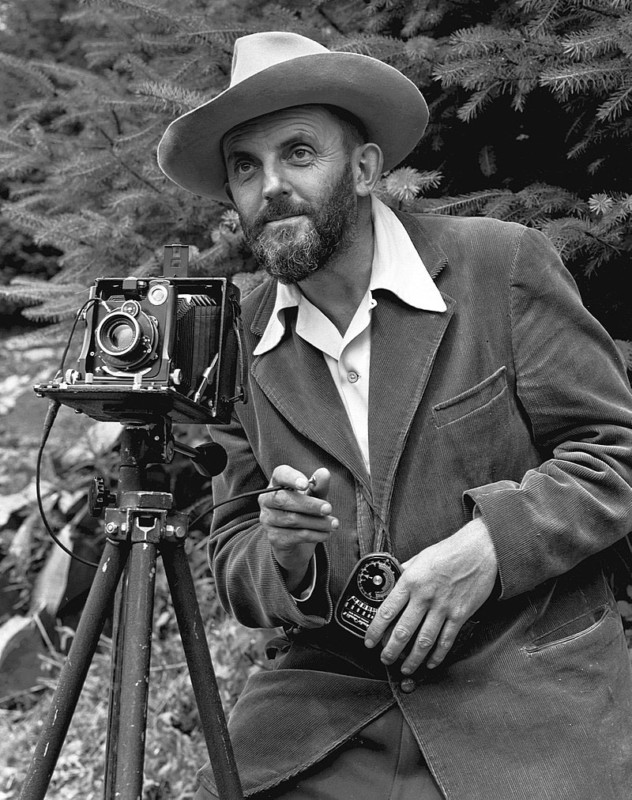

The name of the photographer was Ansel Adams, and what happened that day inspired millions of photographers around the world and changed his life forever. This is the story of one of the greatest American photographers.

Ansel Easton Adams was born as the only child of Olive Bray and Charles Hitchcock Adams in 1902 in San Francisco. Even as a young kid, he was quite special. He didn’t like to play games or sports too much, but rather he collected bugs, enjoying and exploring nature.

He was loved by his father, who supported his only child in everything he could, even though he had to deal with financial problems. His wife, Ansel’s mother, went through depression. Little Ansel suffered from being a hyperactive child, which resulted in problems in school. After Ansel was dismissed from several schools, his father decided to remove him from school and educate him at home.

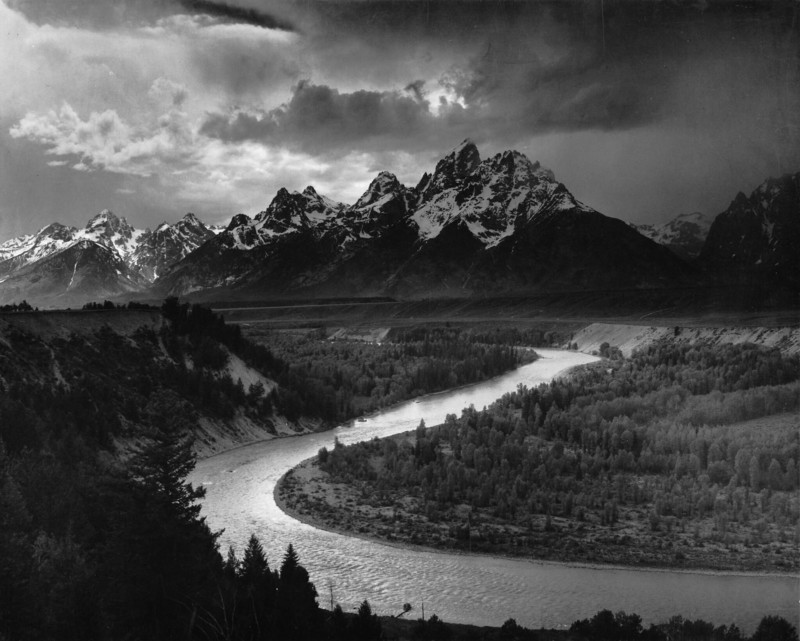

Now, you are probably wondering: how does a hyperactive boy from San Francisco end up being one of the world’s greatest landscape photographers? It was actually thanks to his aunt who gave him a book about Yosemite when he was ill. Ansel was fascinated by romantic stories about Native Americans and mountains. After quite some persuasion, he convinced his parents to visit Yosemite, and when they arrived there on June 1st, 1916, he simply fell in love with it.

“A new era began for me,” he said. It was then that he was given his first camera to document the trip — a Kodak Number One box Brownie camera, a simple wooden box he was able to use to record his memories. And suddenly, all the problems, his demons, the pressure and tension he felt in San Francisco, it all was gone. It changed his life. He found a new love. Yosemite began his home.

“From that day my life has been colored and modulated by the great earth gesture of the Sierra,” he said.

But the path to becoming one of the most well-known photographers wasn’t set all that straight back then. Let’s go back for a moment. One of his great passions was also playing the piano. Actually, not just a passion, it was his obsession. An obsession he adopted and trained intensely. He was said to be a piano genius. But now he adopted another obsession: mountains and photography.

From fall to spring, he practiced the piano for more than 6 hours a day, and in the spring he moved to the mountains. As time went by, he found himself at a crossroads. He really was struggling to define himself as an artist. Music or photography? Yosemite or San Francisco?

At first, chose the one he believed was a higher art-form: music. With this literally heart-breaking decision, he said goodbye to both of his loves, Yosemite and his fiancée. However, after 18 months he decided photography was actually the one thing he wanted to be doing for the rest of his life.

“The music is wonderful but the musical world is bunk, so much petit joins, so much pose and insincerity,” wrote Adams to Virginia, his then-fiancée and later his wife.

He decided to devote his life to mountains and photography. Now that he was fully focused on photography, he still had to solve one problem. You know this feeling when you see a scene but the photograph is not quite like what you have visualized? Adams had it as well. He wasn’t quite satisfied with the photographs he took. Specifically, with the representation of what he saw in his mind and then later on prints.

It was on April 10th, 1927 when he, together with his wife in a small group, was climbing to the Diving Board in Yosemite. He was taking a lot of photographs during the climb and when he reached the final destination to photograph the Half Dome, after the all-day-long hike with his heavy tripod camera, he only had two glass plates left. He could take exactly two shots to capture what he saw.

Carefully, he composed and took the shot. But then something happened. He realized the picture he just took was not going to capture what he was feeling at that moment. With the last plate in his hands, he made a decision. “Visualizing” the effect of the dark sky, he used the red filter to capture the half dome and when he later developed the photograph, he was hooked. He knew he was on to something and it was something he wanted to do for the rest of his life.

Visualization was a concept Adams defined in print in 1934, and later it became a core principle in his photography. He is also a founder of the Zone System. Together with Fred Archer, they put together the principles of sensitometry for determining optimal exposure and development to achieve the best quality in the desired final print. Adams talks about it in the book The Negative: Exposure and Development.

Adams created a portfolio and started working as a commercial photographer. He was obsessed with photography, absorbed in his work on his quest to master the art of photography. He was working nonstop. When he was not photographing, he was in the darkroom printing.

When his first child Michael was born, he was out shooting. When his daughter Anne was born in San Francisco, he was in Yosemite on a commercial job. He really was dedicated to master the art of photography. It is a common theme when we look at the masters in any kind of industry: the dedication and the hard work.

He saw photography as an art form and that is why he didn’t like documentary photography too much. He thought documentary photography, except that which is done on the highest level, was just propaganda, which often actually was the case. During the Great Depression, he was criticized for not photographing the social problems of the 1930s. Even Henri Cartier-Bresson said in the 1950s that “The world is going to pieces and people like Adams and Weston are photographing rocks!”

But Adams was more than ever convinced his photography was about art. What’s interesting is that when you look at it from today’s perspective Adams was actually showing us the problems we are dealing with today: the climate change and the destruction of the environment and our planet; the necessity of the balance between nature and man. We could say he was an environmental activist. He even went to Washington to lobby for the national park.

Slowly but surely, he was also achieving recognition in the art world. He was offered a one-man show at Alfred Stieglitz’s An American Place gallery, which was a great honor.

When we look at the evolution of his photography, he started with Pictorialism, which, simply explained, was a style of photography imitating painting mainly with soft focus and diffused light, to make the photographs more “art-like” from the point of view of that time. But he later abandoned that and dedicated himself to the principles of pure photography — nothing should be in the way to disrupt the brilliance and clarity of his subject.

As his style changed over the course of his life, so did the composition of his pictures. One of the composition changes we can see in his work is how he worked with the horizon. We can see it in the example of probably his most famous photograph Moonrise, Hernandez, New Mexico, which actually has quite an interesting story.

The moonshot seen around the world!

📷 Ansel Adams [Moonrise, Hernandez, New Mexico, 1941] pic.twitter.com/u6qAFjb0ZQ— ICP (@ICPhotog) July 21, 2017

On the road coming back from an assignment to Santa Fe with his son and his assistant, Adams saw something probably only he could have seen. He rushed out of the car, grabbed the camera, and looked for the light meter. It was nowhere to be found. He knew there is a very limited time to capture the moment. He brought the camera at the top of his car and used his experience to guess the exposure and made the shot. He wanted to make a second take; but before he was able to change the slides, the light was gone.

Now, when we look at the straight image he got from the camera we can really appreciate his darkroom mastery.

“The negative is an equivalent of composer score and print is the equivalent of the conductor’s performance,” he said. The idea of how a photographer interprets the negative was important to him. He didn’t just “take” the photographs— he “made” them, which is not something unique to him and his style. Many master photographers used darkroom techniques a lot and Adams never denied that his darkroom mastery was a very important part of his photography.

Adams really wanted people to see his work. He dedicated the last 20 years of his life to printing and working in the darkroom. When he met Bill Turnage, he was finally able to overcome one of his greatest fears and problems with finances. With Turnage’s help, Adam’s archives turned into a multi-million dollar business and he became the first mass-marketed fine art photographer in the world, a very popular icon featured on the covers of magazines.

In 1979 he was honored with the retrospective in the Museum of Modern Art in New York and in 1980 he was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the nation’s highest civilian honor. Ansel Adams died in 1983 at the age of 82.

Being small and tiny but part of this larger wonderful world is a feeling that photographs of the great American master evoke in me. Photography admiring and honoring nature. With an almost religious approach to nature, Ansel Adams was able to transfer his feeling into his photography.

About the author: Martin Kaninsky is a photographer, reviewer, and YouTuber based in Prague, Czech Republic. The opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author. Kaninsky runs the channel All About Street Photography. You can find more of his work on his website, Instagram, and YouTube channel.