I Found NASA Astronaut Gene Cernan’s Missing Moon Camera… on Earth

![]()

It’s often repeated how most of the cameras that landed on the moon stayed on the moon. Astronaut Gene Cernan had been telling the story of how he left his camera on the lunar rover for years, recounting the tale in interviews.

“I left my Hasselblad camera there with the lens pointing up at the zenith, the idea being someday someone would come back and find out how much deterioration solar cosmic radiation had on the glass. So, going up the ladder, I never took a photo of my last footstep. How dumb! Wouldn’t it have been better to take the camera with me, get the shot, take the film pack off and then (for weight restrictions) throw the camera away?”

It’s easy to accept Cernan at his word – he’s an American hero who flew to space three times, twice to the moon – so as far as everyone was concerned, including the press, the camera was right where he said he left it. Plus, a quick scan of the Apollo 17 stowage list reveals no mention of a lunar surface camera splashing down with the command module. So why the mystery?

Looking closer, there’s a sprinkling of evidence in photos and transcripts that suggest his camera did in fact return to earth, contradicting both the 1972 NASA inventory and the astronaut. No, don’t cue the dramatic music… there’s no mischief or intentional deception here. I believe Gene Cernan did leave a camera on the lunar rover, just not “his.” Memory can be a fickle thing, even for heroes, and that rings especially true in this case when the story involves not one camera, but three.

A tale of three cameras

When you’re going to the moon, you’re assigned a camera with a 60mm lens that gets strapped to your chest to document samples, experiments, and the lunar terrain. Both astronauts get their own, clearly labeled with a sticker on the side: “CDR” for commander and “LMP” for lunar module pilot, but they weren’t mutually exclusive, often being swapped throughout the mission based on what film they were shooting with.

On Apollo 17, Jack Schmitt – LMP and geologist extraordinaire – was set up with the black & white film. When he needed color, he’d grab Cernan’s camera and vice versa.

A third Hasselblad camera was also to be used on the mission; it was a bit of a beast really, boasting a 500mm telephoto lens meant to capture distant lunar features for, you know… science. Of the two astronauts, Cernan got stuck looking down the barrel of the 500mm the most, so it’s entirely possible that this is the camera he remembers leaving on the rover. In fact, the post-flight analysis of the transcript pretty much confirms it. But what happened with the other two?

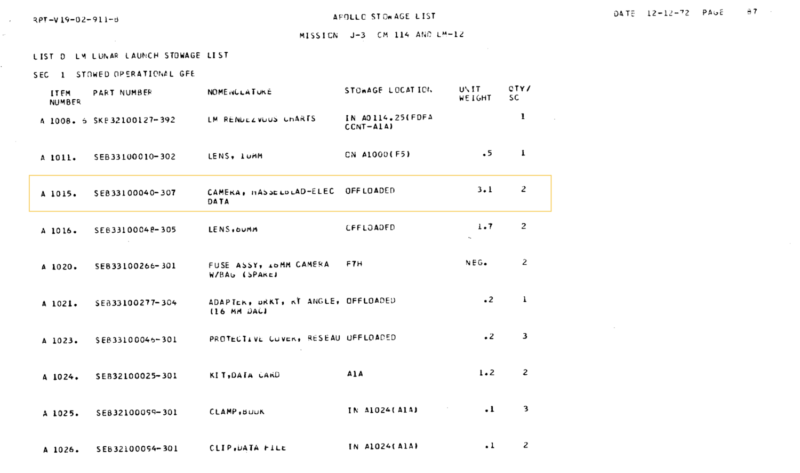

The stowage list says they stayed

A little background. As each Apollo mission launched, NASA prepared a final stowage list that documented all the equipment aboard, detailing what was to be transferred between each spacecraft before and after landing on the moon. This list was then revised in real time as plans changed due to time or weight restrictions.

In the latest revision of the Apollo 17 LM Lunar Launch Stowage List, dated December 12th, 1972, the three cameras that went down in the LM are all marked as “offloaded,” meaning they were left on the surface. The problem is, they launched from the moon on December 13th! So if extra items were brought onboard, it’s not recorded. At least not in what’s available online.

The audio says otherwise

The next logical step was to check the transcripts to see if it was possible to follow the cameras by listening to what was happening. As you read the following excerpt, Cernan and Schmitt are both standing by the final resting place of the lunar rover at the end of their last EVA.

169:29:44 Parker [Mission Control]: …and, Jack, we’re making plans here, to change the camera usage at the end of EVA here. And we’re going to let you take Commander’s camera out to the ALSEP and take a few photos which people think we need. And Gene’s going to take your camera out and document the geophone, when he deploys it. We will not deploy it for the long-term experiment, however. And we’ll bring both (cameras) back, and carry them to the ETB when we get done.

169:30:17 Cernan: Okay.

[When he said “document the geophone”, Bob may have been referring to documentary photos of the seismic charge Gene will deploy near the VIP site. “When he deploys it” probably refers to the charge and the phrase “we will not deploy it for the long-term experiment” refers to a planned deployment of the camera on the Rover seat as indicated on checklist page CDR-32. Specifically, the checklist calls out “Pos(ition) LMP cam(era) vert(ically) on seat.” Gene remembers that he did put the camera on the seat, with the lens pointed at the zenith. Presumably, the intent was to recover the camera at some future date to get information of long-term exposure to the lunar environment.]

[Cernan – “Parker said ‘We’ll bring them both (that is, both cameras) back,’ but I know what I did with that camera. I left it on the Rover pointed straight up. That’s what I planned to do and that’s what I did. I can remember specifically wedging it – I don’t remember exactly where – somewhere up between our seats.”]

>>>> Fast forward to where the astronauts are now back at the LM >>>>

170:39:59 Parker [Mission Control]: Okay, and we gather an ETB coming up with two cameras in it.

170:40:04 Schmitt: ETB’s next. (Pause) (To Gene) Got an ETB? Yeah. (Pause) ETB has two cameras.

Ok, let’s unpack this:

- NASA deviates from the flight plant requesting the astronauts swap cameras: Schmitt is to return to the LM with Cernan’s CDR camera, and Cernan is to use Schmitt’s LMP camera at the rover.

- When they’re done, both CDR and LMP cameras are to be brought back into the LM using the equipment transfer bag (ETB).

- On Gene’s cuff checklist was an item to “Position the LMP camera facing up on the seat of the rover,” leaving it behind, but because NASA had just asked for that camera to be returned, Gene, following the checklist, positions the 500mm in its place, returning to the lunar module with the LMP in hand.

- Two cameras, the CDR and LMP, are then confirmed in the ETB going up to the LM.

>>>> Fast forward again to the astronauts inside the LM after a rest period >>>>

183:40:17 Fullerton [Mission Control]: Challenger, Houston. One update for the post-sleep procedure. I understand you brought in the LMP’s camera, and we want to be sure you get that into the jett bag before the final jettison here. And, by the way, you’re Stay for that final jettison.

183:40:39 Schmitt: Okay, Gordy. It’s already in the jett bag, thank you. (Pause)

[Cernan – “Obviously, I did not leave the LMP’s camera on the Rover pointed at the zenith. But I swear I put something there. It’s possible it could have been the 500 lens, because we didn’t bring it back and I mentioned it was under the seat. I know that I did something with a camera. Now, it could have been a lens. And I stuck it between the seats, sort of wedged it in somewhere, and pointed the lens toward the zenith.”]

[Schmitt – “Houston wanted us to jettison the camera because they didn’t want us to take pictures of Ron Evans’ EVA. They had decided it was too cumbersome and too risky. But, we were going to ignore them, and we figured out how we could do it. But we needed a camera. Ron had a camera, but it was not EVA-qualified.”]

[Cernan – “We had made up our minds we were going to take pictures of Ron.”]

[Schmitt – “And we needed a lunar-surface camera to do it.”]

[Cernan – “Now, we did put the LMP’s camera in the jett bag, so we must have had mine.”]

*Click*. Finally, we have some clarity. One 500mm camera stays behind, and of the two that go up into the LM, the LMP camera gets jettisoned back to the surface before launch. Cernan’s camera leaves with them as they blasted off live on TV and in color.

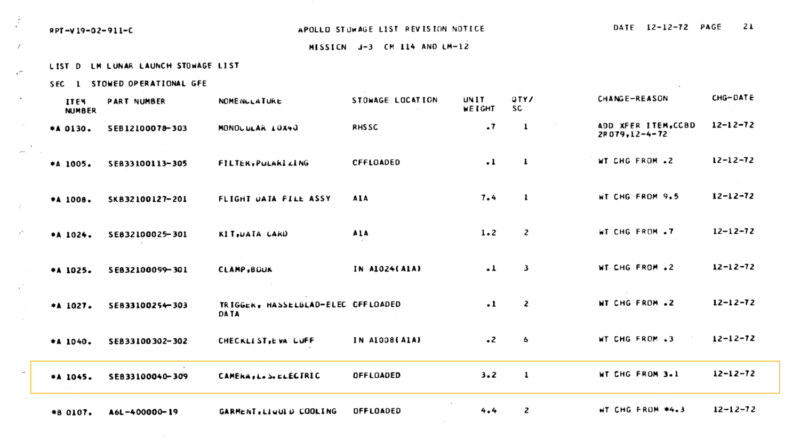

The photos confirm it

Every lunar camera has a unique serial number, usually etched into a piece of glass that’s pressed against the film plane. It’s known as the Réseau plate, used to help scientists both accurately measure objects in view, and identify what camera took what image. By simply looking through the photos captured on Apollo 17, we know Cernan’s CDR camera was S/N 1023, and Schmitt’s LMP camera was S/N 1032.

Granted, those numbers are not always visible, and are really easy to miss… I challenge you to scroll back up to the first photo in the body of this article to find the “23.”

A close examination of photos taken after the astronauts ended their last EVA show both cameras onboard the LM, and only Cernan’s CDR camera in lunar orbit.

![]()

![]()

From there, the trail goes cold

That’s all we’ve had for quite a while. Gene Cernan’s camera, at least publicly, was on the moon, and privately it wasn’t certain, even as late as 2014 when another lunar surface Hasselblad was being erroneously auctioned as “the only camera to come back from the moon.”

CollectSpace was quick to point out transcripts that described other cameras coming back, like Ed Mitchell’s Apollo 14 LMP camera currently on display at the Smithsonian. The information was later corrected by the auction house.

Even then, the question remained: where was Gene Cernan’s camera? Was it jettisoned with the lunar module? Not likely, since the astronauts consciously recall keeping it for Ron Evan’s EVA, which happened on the way home after undocking with the LM. If it did splash down, does anyone working at NASA today remember what happened? Was it lost to a private collection or hidden away in the archives of a museum?

It’s in… Switzerland?

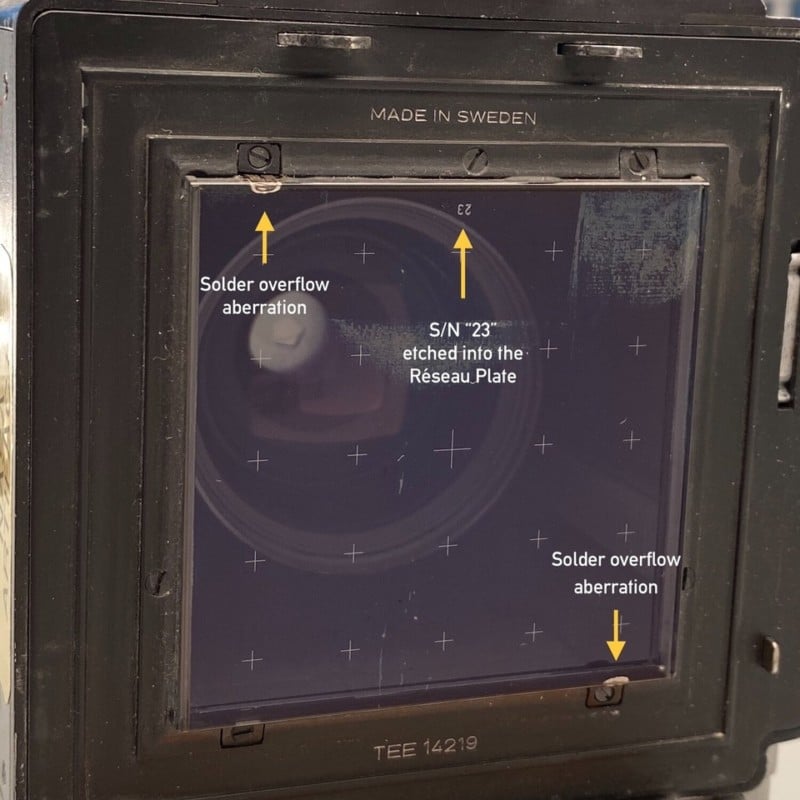

Flash forward to February 29, 2020: While I was researching a detachable polarizer used on the moon, new images of a lunar Hasselblad popped up on Instagram from Swiss photographer Marco Nietlisbach. No mention of its history, just a simple description “Camera: HEDC (Hasselblad 500 EL Data Camera) with a Carl Zeiss Biogon f5.6-60mm lens.” So I reached out.

Marco is Head of Professional Services at Light & Byte, a photo equipment supply shop based in Zürich. Its close proximity to Omega, the manufacturer of most of the Apollo moon watches, had afforded Marco a unique and rare photo opportunity: shooting “a real moon camera” which was on loan to the Omega Museum from NASA.

Whether the camera was flown or not wasn’t known by photographer or museum curator.

![]()

![]()

Now, as someone that’s been researching lunar cameras for half a decade, the camera immediately jumped out as authentic. One thing that caught my eye was the CDR sticker. There aren’t many accurate examples of lunar cameras online – many of the images you’ll find are a combination of commercial and replica parts based on loose information. Of the accurate examples, only flown cameras have this sticker.

When higher resolution photos arrived via email a few days later in March (Marco was very kind to share them as they’re a fantastic polarizer reference) I was able to get a closer look at the camera, and more importantly, the part and serial numbers: P/N SEB 33100040-307, S/N 1023.

Hmm. That got me thinking. If it was flown and used on the surface, there were 6 possible Apollo mission commanders it could have been assigned to. Apollo 11 didn’t use CDR stickers, so it was easy to exclude that mission. Scanning the stowage lists for the “-307” suffix on the part number identified it as a later camera, likely Apollo 15 forward, which whittled the list of possibilities down to 3 commanders. I started with the last mission, Apollo 17, searching for the “23” serial number at the bottom of every photo.

No. Expletive. Way.

Not 5 minutes into looking, there it was. Could this really be Gene… Cernan’s… camera?

At the time I remembered the story he had told countless times, having just finished watching yet another Apollo documentary. Like everyone else, I thought it was on the moon! Well… “everyone” as in the small circle of people as obsessed with this sort of camera history.

I immediately fired up Photoshop to compare the Réseau plate images in my inbox to photos taken on the surface, flipping the layers on and off until everything was aligned. It was perfect. Even the little bite marks from where the glass was attached lined up.

Matching the serial numbers and solder overflows to a photo taken on surface:

![]()

Proof

Gene Cernan’s Apollo 17 camera is not only on earth, it’s at the Omega museum in Switzerland.

Closing my laptop, I went on a walk feeling like I had just found Captain Kidd’s treasure. Was I the only person that knew where this camera really was? In talking with Marco about the photoshoot, and a friend at the Smithsonian, it was clear Omega didn’t get all of the info when it was transferred over from NASA. I haven’t found any documentation of the camera’s journey since splashdown, but it appears it could have been in storage before being loaned out in prep for the 50th anniversary of Apollo 11.

Could it be possible that NASA didn’t remember? I mean, 48 years is a long time, and the documentation from the era is super spotty.

I’ve spent the last four months since that walk in early March trying to trace the camera’s journey from the surface back to earth. I’ve also reached out to NASA to confirm what documentation they have on the artifact. I’ll update this post when they get back. It’s entirely possible this information is known internally, but having little access to the archives during a pandemic makes research quite difficult.

In the mean time, it’s in excellent hands at Omega, receiving the white glove treatment whenever it’s handled. As it should be. It’s a camera that captured some of the most iconic images of Apollo, and was used by the last people to step foot on the moon.

A special thanks to Marco Nietlisbach for sharing his wonderful images and unwittingly kicking off this journey. Feel free to check out his photographic work here.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

About the author: Cole Rise is a photographer, pilot, and space camera maker currently based in Asheville, North Carolina. You can find his photographic work on his website and Instagram. You can learn more about his space camera work and forthcoming documentary here. This article was also published here.