Teen Vogue is Teaching People How to Safely Photograph Police Misconduct

![]()

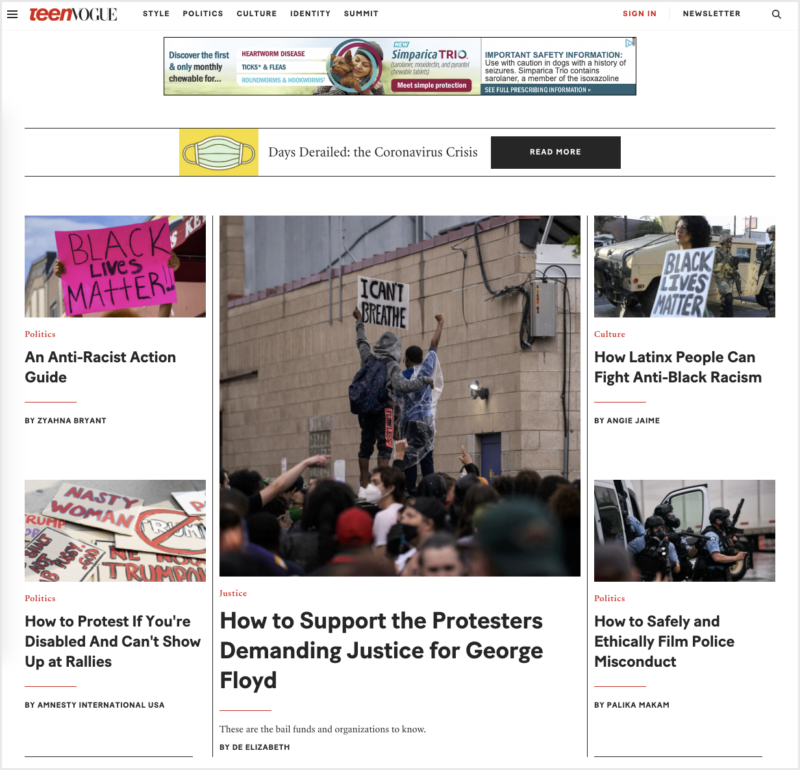

You want to know how to film police misconduct safely and ethically? Teen Vogue will teach you how. Wait… what do you mean Teen Vogue? The fashion and beauty magazine targeted at 18 – 24-year-old American girls? Yes, that’s the one.

What’s more, it does it really well, with a wealth of details suitable for seasoned photojournalists.

The article recommends, for instance, securing your phone with at least a six-digit password, not just touch ID, face ID, or a pattern lock. It’s also important to set the phone to automatically back up to a cloud service like Dropbox or Google Drive. That way, even if the phone gets broken, lost, or confiscated for any reason, a backup of the video has been saved.

Teen Vogue also suggests capturing a clock, your smartphone home screen, a newspaper, or something else in your video that helps verify the time and date. Street signs, landmarks, or exteriors of buildings should also be filmed to help determine the location. And make sure your GPS location service is on.

The article is full of practical advice. The author, Palika Makam, is senior coordinator at Witness—an organization that “helps people use video and technology to protect and defend human rights.”

Founded in 1992, Witness helps activists to document evidence of war crimes, change discriminatory laws, secure justice for survivors of gender-based violence, protect indigenous lands against extractive industries, report racist incidents, expose sex trafficking and forced evictions, and establish legal protections for some of the world’s most vulnerable people.

In other words, it teaches activists how to shoot video that meets the standards for legal evidence, ensuring that perpetrators are not merely exposed — they can also be prosecuted.

The instructions published by Teen Vogue are reminiscent of those put out by Demotix for photographing in hostile environments and conflict zones.

Remember Demotix? It was a photo agency established in 2009 that accepted contributions from professional and amateur reporters alike. They assembled an army of 30,000 photographers around the world who produced 4,500 stories every month. The platform contributed to the growth of “citizen journalism” (news reported by ordinary citizens) and helped many professionals, including myself, find new clients.

The instructions on their website were a valuable contribution to photographer safety, while simultaneously calling for accuracy in documenting the facts.

Demotix proved to be particularly effective at covering news the mainstream media couldn’t reach or wasn’t willing to touch. They were often the first to obtain photographs of riots and wars, or insights that only a local person could possibly provide. For us professionals, it represented both an opportunity for expansion and a threat (because it created competitors). For photography in general, it was an important innovation.

Demotix was acquired by Corbis in 2016, and that’s when its decline began, followed by its closure.

In any case, Teen Vogue is not a photojournalism agency, but a magazine originally created to talk about fashion and beauty. But the editorial line changed to embrace current affairs and politics when Elaine Welteroth took the helm from 2016 to 2018—she is particularly concerned with social injustice and motivating young readers to became socially engaged.

Today, Teen Vogue describes itself as “the young person’s guide to saving the world.” The brand description on the Condé Nast website reads:

“We aim to educate, enlighten and empower our audience to create a more inclusive environment (both on-and offline) by amplifying the voices of the unheard, telling stories that normally go untold, and providing resources for teens looking to make a tangible impact in their communities.”

Readers are not treated as consumers to be fed exclusively with the latest fashion news, but as empowered actors with potential to develop. The publication of tips on filming police misconduct should, thus, come as no surprise. Especially now with recent events triggering a new escalation of violence in America.

This, in any case, is a very significant signal for us photographers. Amateur videos and photos have a growing importance in the information industry and the material obtained by a teenager with a mobile phone documents history just as much as the images of a professional.

Our role changes and evolves. Never before have our expertise and professional ethics been more crucial. If our work can be done by a Teen Vogue reader with a mobile phone, perhaps we are no longer useful. But can it?

This question is pertinent throughout news reporting. For instance, The New York Times has pursued a clear-cut editorial line for some time now: not stop at the facts (which can be found on Twitter), but add critical insight, in-depth analysis, and reputable points of view. This has allowed them to evolve and adapt better than others to a changing world.

They do use a great deal of amateur material in reconstructing the news story, but the reader finds value in the accuracy and reliability of that story and in the analysis and references to the greater historical and social context that follow. The raw material is organized by qualified people who check the facts, connect the dots, and give the story the depth that isolated facts and events lack.

For those of us who shoot reportage (I hardly do anymore) we have to recognize that there are a lot of teenagers out there with mobile phones, and they are the ones who are most likely to be in the right place at the right time. And they quite understandably want to share what they witnessed.

But professional photographers can offer something more: we can produce reliable, in-depth reporting, research, and add the insights that only long experience can bring.

I know the Teen Vogue tips raised some eyebrows among my colleagues, but I personally welcome them. It’s not photojournalism; much of the time it’s simply documenting a crime. And that, unfortunately, is becoming more and more important.

The article in Teen Vogue concludes: “Keep fighting and keep filming.”

About the author: Currently based in Milan, Enzo Dal Verme is a portrait photographer that has been working in the photography industry for over 15 years. His work has been published in Vanity Fair, l’Uomo Vogue, Marie Claire, Glamour, The Times, Grazia, Madame Figaro, Elle and many other magazines. He recently published the book Storytelling for Photojournalists. You can follow Enzo on Twitter and on Medium, where this article was also published.