An Interview with Photographer Joe McNally

![]()

Joe McNally is a photographer and a storyteller. The word photography comes from Greek and means to write with light. That, in a nutshell, is what McNally does: he a writes with light, whether it be daylight or Speedlight. And for a student who started out as a writing major and ended up being a photographer, that is just the perfect result.

In the heyday of publishing, McNally was the only photographer who had the cover of National Geographic and LIFE on the newsstand simultaneously.

Faces of Ground Zero, Portraits of the Heroes of September 11, 2001 Collection is one of McNally’s most well-known works. It is a compilation of 246 Polaroid portraits that are life-size and at 40×80 inches (4×9 feet framed) they came out of the camera in that size. The exhibition was seen by a million people in seven cities and along with the book helped raise over $2 million for the 9/11 relief efforts.

Besides editorial photography, McNally has also pushed the envelope of creative imagery to his commercial clients, which include FedEx, Sony, ESPN, Adidas, Land’s End, Nikon, General Electric, Epson, MetLife, USAA, New York Stock Exchange, Lehman Brothers, PNC Bank and the Beijing Cultural Commission.

A Nikon USA Ambassador, McNally has lectured at the Santa Fe Photographic Workshops, Eddie Adams Workshop, National Geographic Expeditions, The Annenberg Space for Photography, Smithsonian Institution, Rochester Institute of Technology and more. His upcoming workshops this summer range from Hawaii to Tuscany, Italy.

McNally’s social media following is more than half a million, and his blog and books, two of which made the Amazon top 10 list, are very popular with photographers wanting to add new lighting and techniques to their repertoire.

Phil Mistry: How did you get started in photography?

Joe McNally: It wasn’t by design. I was in school to become a journalist, a writer and I was required to take a photography class, and that opened up a door for me that I decided to walk through.

And which school was this?

Syracuse University in upstate New York.

And what was the next step?

I stayed in school because I started learning about photography late in my tenure as a student, so I stayed two more years and did a graduate degree, masters in photojournalism at the Newhouse School of Journalism.

I learned a lot though school doesn’t completely prepare you for the real world of journalism. So I went to New York City and looked for work as a photographer, but mostly unsuccessfully. I took a full-time job as a copy boy at the New York Daily News, which was a major newspaper at that time. It was a minor job, but a foot in the door. I spent three years there but was never a photographer.

I was let go in a staff reduction but by that time I had made contacts with a lot of NY services like Associated Press, United Press International, NY Times and I was able to start freelancing for these news organizations.

You have bridged the world of photojournalism and advertising. Which do you like shooting more, today?

There are good assignments and not so good assignments, but no matter what genre of work I am engaged in, I enjoy the aspect of executing the assignment as a photographer whether it is photojournalism or commercial work. Commercially sponsored work dominates our landscape now because many of the traditional magazines that I shot for have disappeared or receded in their power of the budget.

How long have you been a Nikon Ambassador?

This is a rough guess that the Ambassador program has now been running as a full-fledged formal program for about three years. And I have been in the first group of Ambassadors that were asked to join. I have had a long relationship with Nikon and bought my first Nikon camera many, many years ago and have been a Nikon user throughout my entire career.

Wasn’t there a Nikon program even before the Ambassadors?

They have had for many years, Legends Behind the Lens, and I was named in that program as well, but that was a less formal program. It was an acknowledgment, a tip of the hat that you were a Nikon shooter and that you have had an impressive career.

What do you do as a Nikon Ambassador?

It’s an excellent collaboration. When they come out with new gear, they will reach out to some of their Ambassadors to shoot with the gear on assignment to generate material with new cameras and lenses. They will get our opinion on where the technology needs to go, what could be improved, things we need. We have an excellent collaboration on social media and try to promote each other.

Which was your first Nikon?

It was called the Nikkormat FTn with a 50mm lens.

What was your very first camera?

It was my father’s camera called Beauty Lite III [35mm rangefinder], which I borrowed for my photo class. I have it right here with me.

You did the first all digital shoot for National Geographic in 2003, which was the 100-year anniversary of the Wright brothers’ first flight, which ended up being one of their popular covers. Was it your idea to go digital?

Yes. My story editor, Bill Douthitt, and I thought, why not propose this. Digital was at everyone’s doorstep, and Geographic had yet to shoot an entire story with digital material. We suggested that and it was accepted. It was also a future-looking story as it was called The Future of Flight and it all seemed to work at that time to come together as an idea that Geographic approved.

Did you also shoot film just for safety “back-up?”

Nope. I didn’t. I never shot a scrap of film during the entire shoot.

How was the workflow different in 2003 of a digital shoot from what it is today?

Pretty much the same. I was shooting with a Nikon D1X camera, which produced good quality digital files, but they couldn’t stand up to the digital files we have access to now.

I shot to Lexar cards the entire thing, and the biggest card that was available was 1 GB card, which was very expensive at $700. I would shoot and then download, backup on external hard drive, edit in Photo Mechanic, make selects and pretty much what we do now, though now the process has been significantly enlarged through advancements in technology.

You used a Nikon D1X, and today you use a Nikon D5, which is a lot higher quality, but would the difference be apparent in a magazine reproduction?

Yes, I would say absolutely, it would be apparent. Also, a lot of magazines in the early days of digital had a hard time handling and reproducing digital material, and they were a little bit leery of it. It took awhile for the whole industry to come to terms with digital and embrace it fully.

But now, the quality of the cameras is quite astonishing relative to the cameras I grew up with. Yes, you can see a significant difference regarding reproduction and the depth of the quality of the image.

![]()

You started shooting for National Geographic in 1987. Which shoot did you enjoy the most?

The most enjoyable shoot I did was a cover story on The Globalization of Culture [this was before the Internet]. We identified three epicenters of this globalization process, and one of them was India, another was Shanghai in China and Los Angeles in the US.

We took a look at cultural trends and how they were being shared. Our movies get shared all over the world, and we share fashion trends like the tradition of henna from India, certain wedding traditions, music, etc. All these experiences are becoming common cultural experiences.

Which film did you use at Geographic?

Across the board when I was shooting for Geographic, basically shot with Kodachrome—a great deal of Kodachrome 64 and Kodachrome 200.

Is the current Nikon D5 quality equal to Kodachrome?

The images that come out of a D5 are much better than what I got on Kodachrome.

In the acclaimed series Faces of Ground Zero — Portraits of the Heroes of September 11th, you shot a collection of 246 giant 40×80 inch Polaroid portraits. Tell us about the photographic challenges that a 35mm shooter would face when using a camera as large as a single car garage?

I had one experience before 9/11. I had worked with the camera once before and could work it pretty well. It was a combination of old and new technology. I felt that that camera was an excellent instrument to take a look at these people who had intersected with the 9/11 tragedy. It became a vehicle to look at their courage and persona as a human being. It is a formal process, a very formal camera but I found out I adapted to it pretty well.

So, was this a personal project for you? Did you propose this or was it given to you?

It was my idea. I went to Time Warner and sought funding for it, which they gave me almost immediately.

How much was the funding?

My initial ask was for $100,000.

When we shot Polaroids in the old days, we took out the film and shook it to dry. You didn’t, I suppose, shake it dry?

No, what we would do is peel the chemical backing off of it, and the print would be a positive print as all Polaroid is, and it would be laying on the floor all wet. There were big drying racks as each image was about 40” wide by 80” long. We would take the wet Polaroid and lay it on a drying rack and let them essentially cure over the course of a day or two.

What did one exposure of that size Polaroid cost?

About $300.

So did they say they didn’t want you to be trigger-happy and restrict your shooting?

No, that was completely self-enforced. I knew I had a budget and wanted to photograph a variety of people. For 80 to 85% of the subjects, I made only one exposure.

Would you then wait till it was processed to make sure the subject had not blinked?

Absolutely. 90 seconds later I would have a giant Polaroid, and we could go in and take a look at it.

What was the shutter speed on that camera?

There was no shutter speed as there was no shutter in the lens and you would like camera obscura. I would work in a completely blacked out room, and I would pull out a cap off of the lens, and then I would hit a cable release that was attached to a Mamiya RZ Pro II which was bore sighted right underneath the giant Polaroid lens. In a dark studio, the Mamiya would trigger about 30,000 watt seconds of light strobes, and I would simultaneously get a 6×7 chrome and a 40×80″ giant Polaroid.

What was the aperture on the giant lens?

We shot somewhere around f/32, as I recall. It was not a precise instrument in the sense that you had to feel your way to it. We did not have an ISO rating on the film batches. Every fresh roll of Polaroid that we took out we had to test what ISO it was.

How many flash heads did you have to get that kind of juice?

We had 10 or 12 heads. We had multiple 2,400 watt second units firing through silks to create the main light and then accent lights, background lights, etc.

What brand of lights was that?

Profoto.

How did you come to select a white background?

I did not want to use black, also logistically as I knew I would be photographing a lot of firefighters and that could be a separation problem. So white just came to be formal, clean and completely devoid of information. It enables you to simply concentrate on the human being that is in the picture.

![]()

It was reported in April that the NY Times was going to increase their day rate for photography from $200/day to $450/day. How can a photojournalist in New York City using his own equipment work on $200/day?

No, can’t, not possible. They did do the very good thing about moving the day rate from $200/day to $450/day.

That [the old rate] makes life very difficult as a photojournalist. A career, I mean.

It makes it virtually impossible. I congratulate the New York Times for increasing their day rate, but all they have done is bring the day rate to where it should have been back around 1990. So we still have about 20+ years of catching up to do, and of course, that is never going to happen.

Your social media following is half a million to date. To what do you owe that following?

We take it seriously, and we try to be responsible on social media. We try to be consistent; we try to post good material or hopefully, thoughtful stuff. My blog has been an enjoyable thing to write. It kind of reopens doors to my original education in journalism, which was to become a writer; so I find I have enjoyed writing the blog and people have responded. I am very grateful for that, that we have a bit of a voice in the industry.

Lewis Hine, the social documentary photographer, said ‘If I could tell the story in words, I wouldn’t need to lug around a camera.’ Does the photographer of today have to be a wordsmith as well with his blogs and social media to be successful?

Yes, I think it is an absolute necessity to be a thoroughly good storyteller. And that requires an ability to write, as well as shoot. It needs the savvy and the ways of the Internet in getting the story that you are trying to tell out and about, so people can see it.

You have a high level of expertise with lighting. And you prefer to use smaller hot shoe flashlights in multiples rather than studio strobes. Why?

I would say that might be an opinion or conjured up on the Internet because I do teach Speedlights a fair amount. I use both interchangeably.

I have been fascinated with Speedlights for a long time in the sense that when I was doing a lot of global work for the National Geographic, they would often assign me to do exciting and challenging topics that often involved medicine and technology. I would be traveling by myself and would go to these places, and it would simply be required that I would do a little bit of lighting here and there. I was working by myself, so I started getting familiar with the idea of using these small flashes.

On the other hand, I have also done for the Geographic and other clients some really, really big production work: lighting telescopes, lighting buildings, Faces of Ground Zero. All of that is big flash work, so I step in between two worlds very easily. What is the bottom line is, as always, the nature of the job: what does the job require me to do.

The new Nikon SB-5000 has radio-controlled operation. Has that changed your workflow in any way?

It has changed it considerably, and it has enhanced it and made it easier to work with small flashes. The SB-5000 AF Speedlight is quite simply the best Speedlight I have ever worked with.

What is the maximum number of Speedlights you have used in a shoot?

There were a couple of instances where it was pushed out to me to use a lot of Speedlights as a demonstration kind of thing. I would say, up to about 20 Speedlights I have used in a practical fashion on location.

So, how many Speedlights do you typically travel with on a shoot?

I have… I own right now eight SB-5000 and four of the old SB-910. If I am going on an extended trip or someplace where I think I will use Speedlights, we have a case that we take with us, it’s our Speedlight case and that will usually have ten.

You also combine Profoto B1. How many of those heads do you travel with?

We have two B1 kits and they each have two heads in them. Depending on the size of the job we will take one B1 kit, which has two heads or both of them, which gives me up to four. So between the Speedlights and the Profoto B1, I can pretty well light just about anything that I encounter.

Just recently at Creative Live out in Seattle, I brought Profoto Pro-B4 because I knew I needed a big pop of light.

Do you shoot in manual mode or with the TTL automated mode when you are just using your Nikon Speedlights?

It’s really situational. I start off with TTL, which is my default. I can find my way to a good combination, often just using TTL flash. Once I find my way, I often will then simply lock it down into manual because maybe at that point I have a couple hundred frames to shoot and I don’t want to deal anymore with the potential variance of TTL. But TTL is an excellent tool when you are doing fast-moving flash.

Even with 10 flashes or 20 flashes?

Well, when I get myself into a big scenario I find I am using my zones. With the SB-5000 I have 6 zones of control. I can put flashes in A, B, C, D, E and F groups. I will find the mosaic that gets put together in a situation like that. Might have A, C and D group operate in TTL and B and E running in manual.

Do your journalistic portraits have different lighting than your advertising ones?

That’s a good question. It depends on the sensibility of the job. When I am out as a journalist or out on my own trying to tell a story, 95% of the time I don’t have an art director there. So I can follow my nose and hopefully come up with a good set of pictures that speak to the situation.

When you are doing commercial work many, many times, you will have an art director on set with you. You will be shooting their ideas. You will be shooting to a sketch. And that will often tremendously influence the nature and quality of your approach and subsequently, of course, your lighting.

When you were at LIFE, the classical master of all lighting techniques, Gjon Mili was there. Did you know him?

I knew Mr. Mili but in a very casual fashion. I started shooting for LIFE in 1984 roughly as a freelancer and Mr. Mili had his offices up on the 28th floor with the rest of the many other photographers at Time Life. And so I had the great honor of meeting him. I will not claim to be familiar with him or know him and he was an amazing craftsman with light.

So did he influence you in any way?

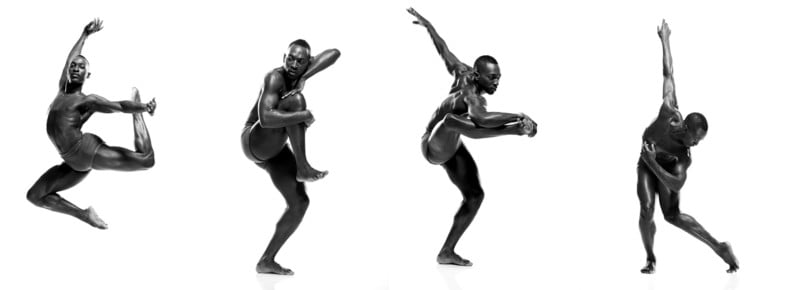

Absolutely, I think he influenced a whole generation of photographers in the way he used light. He was an innovator for sure but also wasn’t just an engineer. He was poetic in the way he used light. His stroboscopic studies of dancers were just beautiful, the way he portrayed Picasso was innovative and in his own way just as daring as some of Picasso’s own art.

He was quite a formal gentleman. I never joked around with Mr. Mili. Just being in the room with him you needed to pay him respect. I always appreciated what he did and it still carries with me. Some of the pictures, The Lindy Hop, for instance, is just a wonderfully exuberantly flash photograph.

You shipped 47 cases of gear to Chile to shoot giant telescopes for National Geographic. What did you have in all those cases?

Mostly lighting, heavy-duty lighting. The big telescopes are 15-20 story buildings. They are enormous and you have to light this very cavernous space inside the telescope, which is never seen as always telescopes are always operating in darkness. I had to light these massive structures.

We would routinely take 10-12, 2,400 watt second cases. So, if you take 12 numbers of 2,400 watt second packs, that is 12 cases right there and then the rest of the heads can be 5-6 cases. So before you leave on the plane, you are looking at 20 cases of just the lighting. Then you have to have ways to support all that lighting, stand upon stand, upon stands, safety wire, clamps, ropes and then you’d better bring your cameras too.

And was there place for your Speedlights in that shoot too?

No. The telescope shoots…I mean, I did have a couple of Speedlights occasionally in the control rooms you could find room to use a small Speedlight, say in front of a small computer screen or something like that but the actual physical reality of telescopes was way beyond the scope of small flash.

What brand of flash did you use?

Profoto. I use Profoto big lights. It is to me the most sophisticated, durable big flash system in the world.

Would you consider doing this kind of shoot with continuous light or light painting?

No, I occasionally did some light painting with the head light from my car, driving it around while the camera is open, that kind of thing. At that point when I was doing the telescope work, LEDs were not in vogue. They hadn’t been developed.

Even so, a big hot light is massively heavy, bulky and dangerous. It gets very hot, needs a lot of electricity and the bulbs routinely break. You don’t have the sophistication of approach: you have barn doors and things like that not necessarily the kind of light shapers that routinely come along with say a Profoto system.

I can take a 2,400 watt second pack, which is sizable but not overwhelming and bang that into a telescope and I can get a lot of play out if it. You would need just a ton of hot light to get the equivalent amount of f/stop out of it.

Digital has many upsides from film, what are the downsides?

You know, I can’t really think of much. To be honest, everybody is always nervous about losing their digital images, but if you are safe and careful, you won’t lose them. To me it’s much less anxiety-producing than putting three weeks of work, i.e. 100 rolls of Kodachrome in a FedEx bag; sending it to National Geographic from a foreign location and not knowing for three days or so whether your package got there. That’s very nerve racking.

You have been described by American PHOTO magazine as perhaps the most versatile photojournalist working today and you were listed as the 100 Most Important People in Photography. But today both American PHOTO and Popular Photography are gone. Do you see a future for print photo magazines, knowing that their news is always going to be one or more months old?

Well, it is the constant dilemma of print to remain relevant in a very fast paced digital world. But I still think there is an absolute need and future for printed photo magazines and printed magazines in general.

The tactile experience and the permanence of actually having a library, a reference point is still extremely valuable. Websites and Instagram and all of that are the currency of the moment, and I think it’s wonderful. But there is room for both expressions and I hope that the magazines that we have left will stick around.

When you photographed Pope John Paul II on a visit to his homeland of Poland you were with 9 other photographers of Newsweek and Time had 14. Would today any magazine commission 14 photographers to cover a single event?

I don’t think magazines would, as they no longer have that budgetary power. But an outfit like Getty would. When I was at the Rio de Janeiro Olympics, Getty had 140-150 photographers, that was what I was told. An agency like Getty has that economic clout; magazines do not.

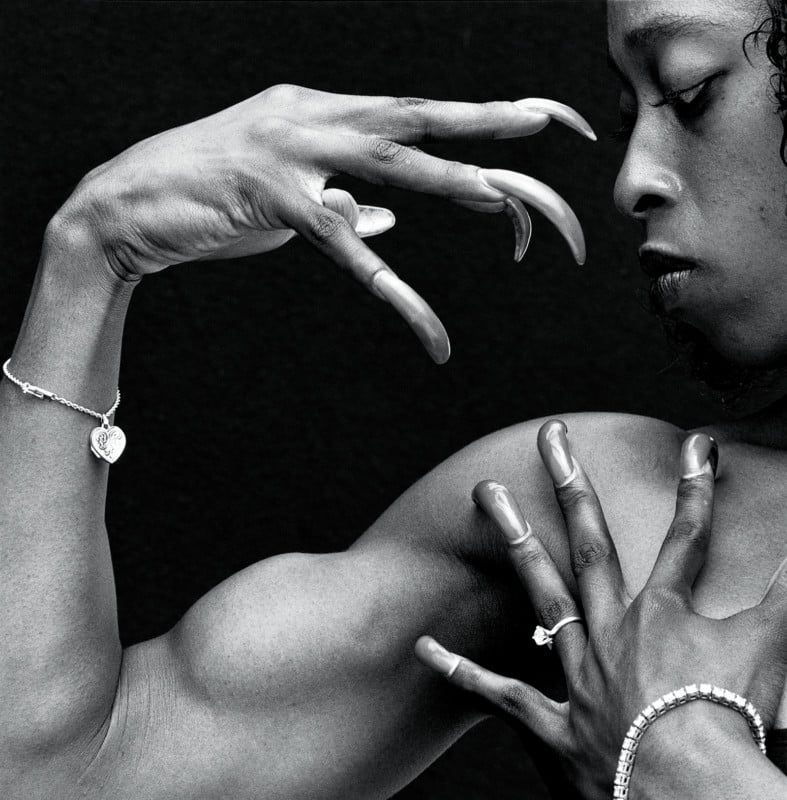

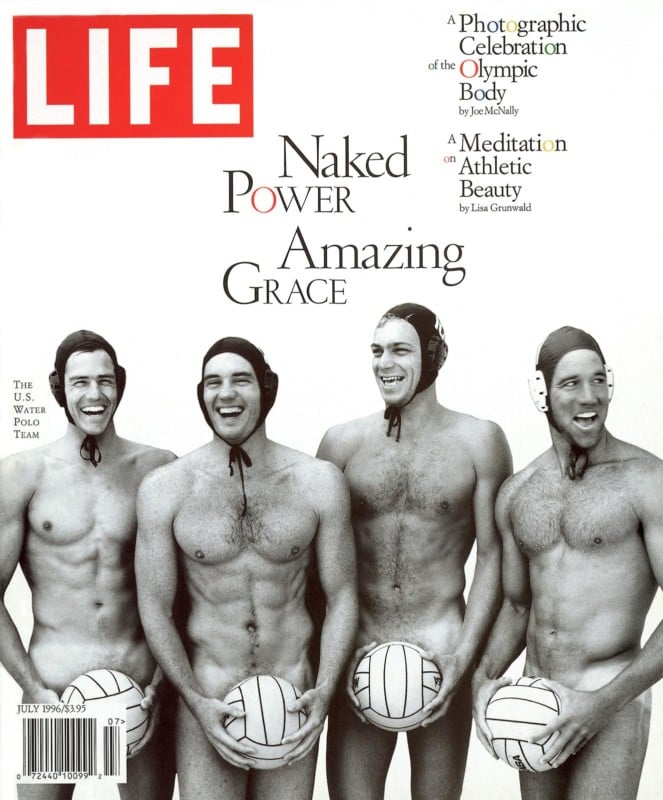

Your much talked about photograph for LIFE showed the members of the 1996 Olympic team in the nude on the cover. How did you convince them to do the pose? Did you clear the shot before with the photo editor?

The magazine was behind it a 100%. My editor at that time, Dan Okrent, was a big fan of the idea. Dan was a risk taker and he appreciated and understood photography. When I got into the field, I found most of the athletes were quite comfortable. I told them it was completely an above-board effort. It was not sensational. I was trying to show their musculature and physical attributes. And they were at the peak of their lives, physically and showed off their physiques.

Which is your go-to lens?

My most popular lens, most used lens would be a Nikkor 24-70mm f/2.8

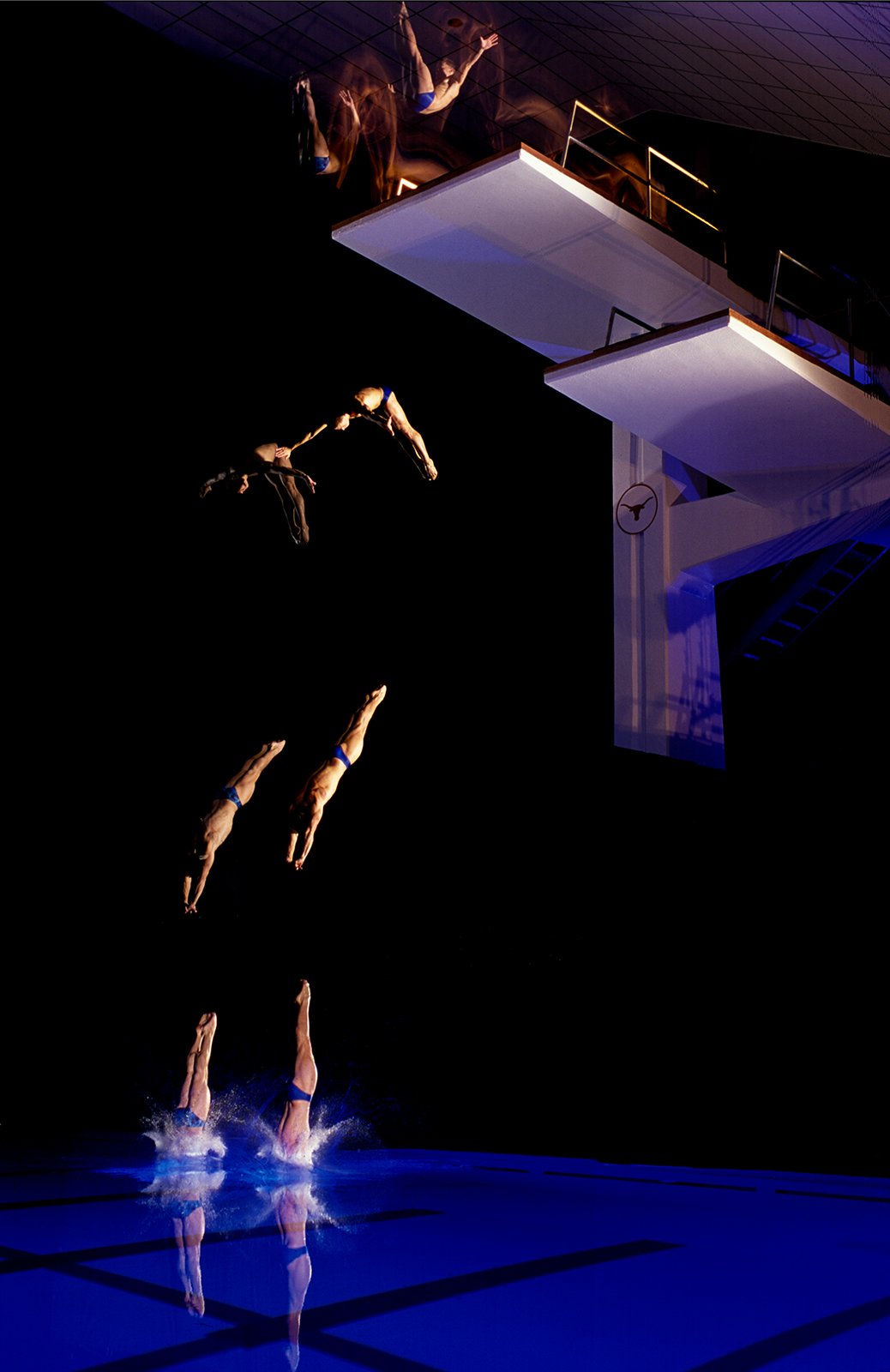

At the 2000 Sydney Olympics synchronized diving was introduced. You shot a four-page gatefold on film that had multiple exposures of the athletes during different times in the fall and also illuminated the pool. How difficult was that?

Lord….the shot took five days and cost Sports Illustrated a lot of dough. We had to turn the diving stadium at the University of Texas at Austin into a giant, stroboscopic photo studio. It meant the divers had to throw themselves off the 10-meter platform in utter darkness, with just a flashlight over the water to give them an idea where the surface was. Shooting film, no digital, no LCD.

I confirmed each try (mostly failures) on a Polaroid camera I fired simultaneously with the other cameras. The divers would be out of sync, and then I would be out of sync. It was a nightmare. Processed each night to see if we got anything. Finally had my frame on the 5th day. Had six zones of flash, five over water, one firing into portholes underwater to make the water blue. Plus hot lights on the top of the dive tower. NEVER AGAIN.

From 1994 until 1998 you were with LIFE magazine as a staff photographer, all by yourself, possibly the first staffer in 23 years? Is that good to be a solo operator?

It was pretty great while Dan Okrent was the managing editor there. He moved on during that time and it became a lot harder to work out longer projects. He had great confidence and knew how important pictures were—a rarity among Time-Life managing editors.

I self-generated a lot of stories, and did anything and everything they threw at me as well. It was a lot of work, but it was welcome. LIFE was actually making money during those Okrent years, but then, after he left, it seriously tanked.

Your Indiana High School basketball feature, which you shot for Sports Illustrated, ran over 30 pages. Would you ever get such coverage in print or even online today?

No, never. It was unusual to get that many pages even back in the day.

You got your Masters in Photography 27 years late. How did that happen?

I never finished my thesis. I left with my entire course work done, but no thesis completed. I was anxious to start a career. They ended up accepting the Faces of Ground Zero book as my thesis, and I am forever grateful.

![]()

Have you ever shot a wedding?

Many, both large and small, but no more.

Can you share with the readers of PetaPixel what equipment is in your kit bag?

Well, you can take a look at my gear page on my blog to see the range of stuff we have. It doesn’t all come into play, obviously. I have done a lot of big production work over time, so I have a lot of lighting, etc.

But the basics are very similar to any shooter. A couple of digital cameras, in my case Nikon D5, usually. 14-24, 24-70, 70-200 lenses go with me virtually all the time. A couple of fast primes like the Nikkor 105 f/1.4, and 35 f/1.4. Three or four Speedlights, the SB-5000 radio TTL units. Profoto B-1 is usually out there with us as well.

Today there are numerous contracts out there to be able to shoot. Would you be willing to sign many of them?

Not many. We walk away from lots of work.

You photographed Cher right after her best-actress winning Moonstruck. At that time you said, “If you can’t make them good, make them big and in color.” What did you mean?

I actually photographed Cher before her win, just as the movie was breaking. It is one of those assignments I look back on as a blown job. The old adage of “if you can’t make ‘em good, make ‘em big and in color” [lay out the photo feature with larger photos and more pages] was an old inside joke at LIFE.

If you could do only one kind of assignment for the rest of your life, what would it be?

Stay at home and stare at my wife, Annie!

You can follow Joe McNally and see more of his work on his website, Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, Pinterest, Google+, YouTube and Nikon Ambassador.

About the author: Phil Mistry is a photographer and teacher based in Atlanta, GA. He started one of the first digital camera classes in New York City at International Center of Photography in the 90s. He was the director and teacher for Sony/Popular Photography magazine’s Digital Days Workshops. You can reach him via email here.

Image credits: All photos © Joe McNally and used with permission