Disassembling a Tripod Ball Head to See How It Works

![]()

This will probably be of limited interest to most of you, but we like to know how things work, not just how well they work. We thought we’d take a couple of pictures when we disassembled a ballhead in case any of you were interested. Our demonstration partner today was a Benro B1 ballhead that had a stripped tension adjustment knob, but all ballheads work basically the same way.

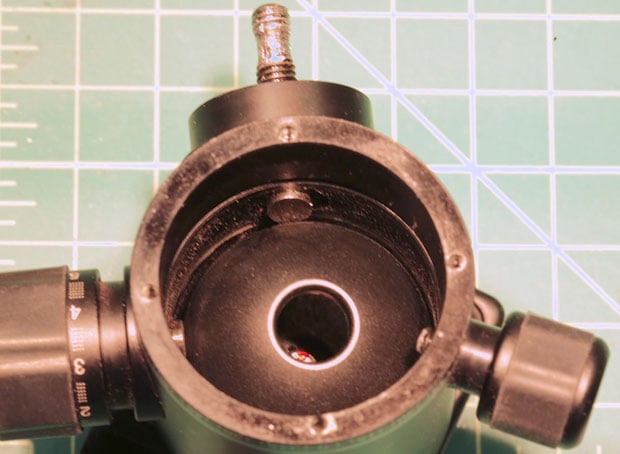

You can see the three knobs of this ballhead. The one on the lower right is the friction knob for the panning (or rotating) baseplate. The left knob and top knob are the lock and drag controls, which pretty much do the same thing (which is why some ballheads only have one friction/locking knob).

You may barely notice that the upper knob is attached to a push rod with a 30-degree angle, while the left knob has a flat push rod. (In this picture the ball has dropped back towards the push rods. Assembled it’s about 5mm further forward, away from the base.)

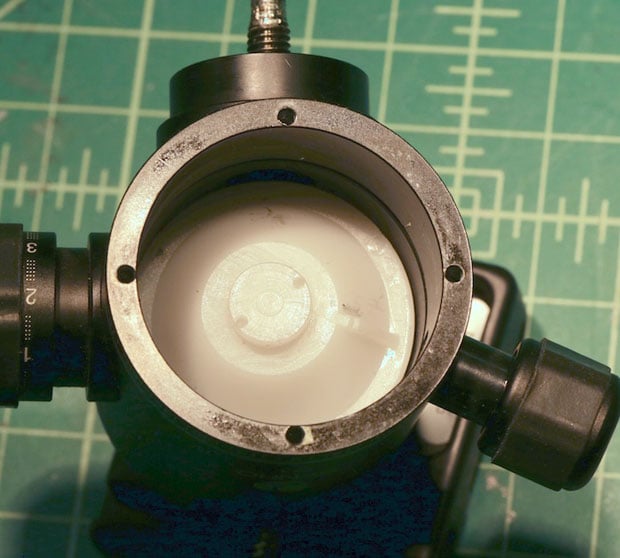

A plastic bearing cup fits beneath the ball. Like the upper bearing, it’s nearly frictionless with no pressure is applied, but grips quite tightly when pressure is applied. Unlike pan-tilt heads, ballheads don’t need internal lubricants.

The next piece is a conical plastic compression ring that fits over the bearing and provides the magic tightening of the ballhead. Notice there’s a partial-thickness groove cut in the cone, which fits over the ridge in the bearing cup, holding things in proper alignment.

On the opposite side there is a gap in the ring. When you turn the friction or locking knob, this opening is compressed. Since the ring is cone shaped, compressing the opening forces the bearing plate more tightly against the ball, increasing friction and resistance. Like I said, simple and elegant.

Of course, the ballhead needs a very sturdy base under the conical plate, so that the pressure from the adjustment knobs all goes up to the friction plate and ball. In this case there’s a 1mm thick steel plate with a 1mm thick steel washer beneath that, held in place with an equally thick e-clip. The remaining space is taken up by the rotating (panning) base plate, which is attached by 4 screws (you can see the screw holes in the bottom of the case).

![]()

Takeaway Message

Ballheads are pretty simple things. Taking one apart shows why, when properly taken care of, they seem to last for ever.

The difference between the best ones and the less-than-best ones isn’t (as far as I’ve been able to tell) any secret new technology. Rather it would be in the materials used for construction. The best heads have aspherical balls and use higher cost materials for the friction plates, conical plates, screws, and housing.

For moderate weight (say a camera and 70-200 f/2.8 lens) used occasionally (a couple of weekends a month) the difference isn’t huge, especially with a new-out-of-the-box ballhead. With heavier weights and heavier usage, more durable bearings and particularly screw stems should improve reliability and lifespan. When we see a ballhead die, 90% of the time it’s because a friction knob’s threads are stripped or the rod bent.

About the author: Roger Cicala is the founder of LensRentals. This article originally appeared here.