A Conversation with Martin Schoeller

![]()

Flip through the pages of any major magazine published in the last few years and it’s likely you’ve seen a picture snapped by Martin Schoeller therein. The German-born award-winning photographer got off to a rough start upon moving to the United States in the early 1990s, only to find himself as an in-demand iconic picture taker today.

He’s covered every major celebrity you can imagine with his trademark close-up portraiture and fashion photos alike (though, he admits fashion isn’t quite his bag). From Paris Hilton to Barack Obama, Schoeller has worked with Hollywood’s elite and America’s most influential politicians. He’s seen it all.

![]()

PetaPixel: What’s your background? How did you get started in the world of photography?

Martin Schoeller: Well, I didn’t know what I wanted to do until I was about 20-years-old and a friend of mine applied to a photo school in Berlin and said ‘Why don’t you apply as well? We can go to the school together.’

Since education is free in Germany, a lot of people apply for these more artistic professions. It’s quite competitive to get into these schools. My friend gave me all of this advice, and in the end I was accepted and he wasn’t. Then I had to move in with him because he already lived in Berlin.

That’s how I really got started with photography.

So I came into it quite late. I think a lot of people start with photography when they’re like, 14 – 15. They always were kind of interested in it. But once I start going to the school I was so relieved that I found something where I felt I could be good at if I try really hard.

It’s kind of until then I knew I wasn’t quite a bookworm. I knew I wasn’t the studious type. It was kind of a great fit for my personality.

Then I worked for a photographer in Frankfurt for a little while. I also worked for a photographer in Hamburg. Came to the United States in ’92. I had to go back [to Germany] because I couldn’t find a job. And then came back [to the United States] in ’93 and ended up, after a while, working with Annie Leibovitz for three years until early ’97. It took about a year in a half to kind of get my first job.

I kept on shooting like crazy on the street, you know? Having no money, I started hanging out at the police station in Newark, New Jersey. I would take the PATH train to Newark from New York, which was only a dollar. I lived on two slices of pizza and a Budweiser beer a day for probably about a year. I had a five dollar spending limit for food a day. So I knew exactly where the cheapest food places are. So it was a little bit rough.

For quite some time, I would take roller blades to get around to save on the token money to drop off my book and pick up my book. It was quite a hassle because you had to drop them off and you had to pick them up. You don’t even get an appointment to see anybody. Having worked with Annie, and a lot of other former assistants that had worked with Annie, it doesn’t necessarily mean that you get to see anybody at a magazine.

In the beginning, my work was very static. I basically photographed people in the same style with an eight by ten inch camera. They were very personal portraits. It was more like face studies. And that didn’t go over too well with photo editors. I’d make them into sixteen-by-twenty-inch prints. I had this big portfolio. People didn’t know what to do with my photographs.

After a while, I came across with the scheme of low-lights and then I started to loosen up and it allowed for more expression to create this look that I’ve been doing ever since then. Still pretty static. So, a very controlled environment. Always the same lens, the same lighting, the same angle. Very similar expression, but there’s a little more life in them than in my earlier portraits. My career started taking off in ’99.

![]()

PP: You noted that you spent time working for Annie Leibovitz. No doubt, one of the most famed celebrity photographers out there. Can you talk more about that experience?

MS: I came to the States because I wanted to work with her, Irving Penn, or Steven Meisel. I thought maybe I could do fashion, which in retrospect is quite funny considering I don’t really care about clothes. But I knew I’d learn a lot from her. I was a great fan of her work and still am.

I had seen a show in Hamburg at the Deichtorhallen and was so, so impressed by her pictures and by that show. It took me a while to have that opportunity to assist her, [and I did] for a couple of days. Somebody had just left and the first assistant liked me and saw that I had a lot of technical knowledge. My school was very technical and not, you know, not very fine-art paced. It was very much about optics, the chemistry, printing, and color temperature. He kind of liked it.

My English was really bad back then. So anyway, he really liked the idea of having a technical backup. I thought I was fairly qualified, but I was pretty much totally overwhelmed for the first year. I mean, you think you know so much coming out of photo school and then you work with a professional photographer [on] these huge set-ups. It’s like stepping into a whole other league. A whole other stratosphere.

PP: So you were intimidated?

MS: I was intimidated, and fascinated. It was like the most exciting thing, you know? We worked insane hours. It was a roller coaster ride. And I was, at times, third assistant so I would only go on shoots in Manhattan or, you know, around New York where we’d drive to. A lot of her work is done outside of the city, so I’d stay back and organize the equipment room.

While working with her, the other assistants left pretty quickly and then I became her first assistant in charge of lighting. And that’s when it got really intense. She’s very demanding and she’s often known impatient in photo shoots. You’re often running out of time and can’t play around with the light.

You have to know what you’re doing. You have to work immediately. People get impatient having their picture taken. They don’t want to sit and wait around. So I learned so much because she gave me so much responsibility, but with the responsibility also came the burden if things didn’t go so well. It got pretty heated sometimes. But there’s no way I’d be where I am now without having worked with her. I think I owe a great deal of my success to Annie.

![]()

PP: Did you come out of the experience having a plan? In other words, did you know what you wanted to do specifically once you stopped working for Annie?

MS: Well, I kind of felt like I wanted to do what Annie’s doing. I never thought I’d be as successful as I am now. Or that I’d get these high-profile jobs. But I knew I wanted to be a magazine photographer. That’s what I came out of [it thinking]. I thought what a great, cool job. I love all the traveling, the challenges that come with it. I felt like that’s what I wanted to do myself. I thought having worked with Annie I had a good starting point. But then working for somebody and doing the lighting and then doing everything yourself. That was another quite steep learning curve.

PP: You mentioned earlier your portrait style. Can you talk about the development of the portrait style you’re famous for today?

MS: When I left Annie I had done a lot of photo shoots in those few free days that I had and I tried fashion shoots and portraits of friends of mine. And I never thought those [close-up portraits] would be the ones I’d want to take in the future. I just had one idea for one project and then made it happen.

I went to the police department in Newark, New Jersey to photograph all the cops and make friends with them. Ended up in the homicide squad, and car chases, and photographed those police officers arresting people, people getting beaten up, and people being dead on the streets. So then that was another thing I did.

And then I ended up doing a whole series on drag queens. I never really thought ‘Oh, this is the career I want to have, and this is going to lead to this, and this is going to lead to that.’ It’s hard enough to come up with an idea. If you start over thinking it, and looking too much in a sense of what has been done in the past, I think you end up doing nothing.

In retrospect I think it was good I was slightly ignorant. I just kept on taking pictures. Eventually, these close-ups were the pictures that people responded to the most. I felt the strongest about them myself, so I kept them doing more and more of those. But if I wouldn’t have gotten all the other pictures over the years, I probably I wouldn’t have ended up doing them. It wasn’t a like a concept that I thought would ever be taking off. It was just one of many things I was working on.

![]()

PP: Do you think these close-ups are something you’ll continue doing for the rest of your career? Will they stick with you?

MS: Yeah, you know, I made a mistake and stopped doing them for a while. A friend of mine said ‘Oh, you got to reinvent yourself, you’ve done a lot of those.’ Then I started doing them a little bit differently. I even started shooting with an eight-by-ten-inch camera. But I will keep on doing them now.

I think It’s important to have one style. There’s no reason to stop doing it, really, because Richard Avedon took all of his pictures in front of a white background. With an eight-by-ten or something and a medium-format camera. I mean he never changed his style, ever.

He barely showed a color picture. So why would I [stop taking them] now? After I’ve been doing them for fifteen years, why would I think ‘now I’m going to start doing some self-portraits’?

Magazines like them, people like them. That’s telling. Why would Diane Albus now all of a sudden start shooting color or change up her lighting? She did the same thing all of her life. Weegee did the same thing all of his life.

It doesn’t mean I can’t do other bodies of work that I can light differently, or that are very differently conceptually. I’m still in the same position I was fifteen years ago. You get an assignment, and you have very little time with somebody. You’re in a location that you haven’t chosen, they’re wearing something that you might not like. But [with] the close-up you’re in this fortunate position of always walking away with something where nothing else but the person matters.

It doesn’t matter where they are or what they’re wearing. So it feels like an honest portrait that sometimes is impossible to take given the circumstances that you’re handed.

PP: You do a lot of work for fashion magazines like Vogue and Vanity Fair. But you mentioned earlier that you’re not particularly interested in clothes. So where does your real passion in photography lie? Is it doing the close-up images you talked about or is there something else that you enjoy doing as well?

MS: Yeah, I love doing the close-ups. You know, I really enjoy working for magazines because they pay [me] to go to places, they pay [me] to meet people, to research people. I mean, if people say ‘what’s the most exciting assignment you ever had?’ Then I probably would have to say where I find myself the happiest and not as stressed out, and just like having a great time.

I’ve been sent to photograph one of those indigenous groups [in Brazil and Tanzania]. I was basically there for a month and then hanging out with this group of people that still goes hunting and gathering. I didn’t have to come up with concepts, I didn’t have to try to talk to anybody into anything. You know, and I could just watch these people and hang out.

You can’t even really talk to them because you don’t speak their language. So you depend on some translators and then they’re not around. So you just become this entity in the village where everybody more or less gets used to. Some people are just smiling at you and you’re just sitting there on a rock and watching life go by in this environment that is so, so foreign to us.

And I always love those assignments because you get to climb out of your tent with your camera around your neck and there’s no publicist, no stylist, no make-up people. I have an assistant with me but often I went along by myself. They remind me of my old days of my photography career.

![]()

PP: Who were those shoots for?

MS: One was for The New Yorker, a short trip. And then another one was for German Geo. And then I’ve done two for National Geographic and then I was once in Africa for Travel + Leisure.

Sometimes I try to talk people into doing a story on a tribe in order to [go]. It’s so expensive to go there, and authorization is difficult to come by. So it’s good to have somebody sending you rather than me spending all that money trying to do it on my own.

![]()

PP: I wanted to get your opinion on something. Do you think once you start doing photography as a career that it becomes less interesting to do it as a hobby?

MS: Yeah, that is definitely true. I’m taking pictures of my four-year-old quite a lot but honestly I’ve taken them with my phone. You know, I’m too lazy to carry around a camera, it’s kind of pathetic.

I’m not taking a Leica and doing contact sheets, which is something that I should be doing and I probably will regret later. I have done some close-ups of him over the years but that’s pretty much all.

So yes, it is true because as soon as a camera is involved you feel like you’re working.

For me, looking at magazines is stressful because you constantly reflect on everything you see. I like to go to shows, and museums, and exhibitions but it’s always something that’s visual and could change my views. It’s all stimulation, but it’s also professional stimulation. It’s not just entertainment. It is kind of stressful. It feels like work, so sometimes you don’t want to do it.

PP: So, I take it you’re not really attracted to taking pictures when you’re not on a job, or do you? You mentioned you like to take pictures of your four-year-old. Is there anything else that you like doing, or you pretty much limit it to that?

MS: I love taking pictures of him, but you know, I just take them with a phone snapshot. For me that really doesn’t count. You know, people think that aiming your telephone at something is the same as taking a photograph. It’s just basically such a passive thing. You’re not really thinking about it, it’s just: ‘oh, that’s cool, click’.

Everybody is a photographer nowadays on Instagram but those pictures are all, you know, basically snapshots. Like, they’re blurbs. They’re not really photography in the sense of, there’s no concept behind it, no thought, nobody is being directed. It’s just like ‘hey, look at the camera,’ you know?

I mean, it has its own needs and its own purpose but you can’t really take those pictures that serious.

![]()

PP: But back to the question. You don’t really spend much time taking pictures outside of assignments, or do you?

MS: I mean, outside of assignments I do. I’m going back to the tribe that I photographed last year for National Geographic, and I helped them organize a meeting of chiefs, financially. So I’m going back to Brazil on my own dime to photograph all of these chiefs that are coming together. So I do that, you know? It’s not an assignment. I’m just doing it for myself.

I do personal projects here and there. Family pictures, or very often friends. But I never have a camera with me. I’m not somebody who goes out for dinner with a camera and constantly wants to be thinking about what picture to take. If that makes any sense.

PP: What do you say to someone who is trying to get into photography? Also, I wonder if you have any advice for hobby photographers who are trying to find inspiration or style.

MS: Well, I think the most important thing is to, well, a number of things . I have a 23-year-old son who’s going to the same photo school I went to, and I see a lot of people that go to school with him. Some people just don’t take photography serious enough. It depends on what you want to get from it. If you want to have fun, do whatever you want. But if you want to take great pictures, then it is not something that is to be taken lightly.

If you want to be a good photographer, think of somebody who wants to be a lawyer. And not just an okay lawyer who helps some people not get kicked out of their apartment or someone who deals with a simple contract loan. If you want to be one of the best lawyers or whatever field of law you might be in — those people work twelve hours a day, fourteen hours a day. Maybe not all of their lives but at least for like ten years of their lives.

It’s such a huge time commitment. If you want to be a photographer, you have to take it serious and you have to be willing to work as hard as anyone else who wants to be successful in any kind of field would have to do. You can’t just be like ‘I’m an artist, and I’m looking at magazines, and I’m going to some shows, and then I chat with some friends about the latest equipment, and then I retouch some image for five hours, and then that was a work day for photographer.’

I think most people spend too much time looking at pictures, too much time talking about pictures, too much time on Instagram, too much time on Facebook, too much time on all the social media, and so preoccupied with — they think if more people see their pictures, the more valid of a photographer they are and the more important their pictures become.

Photography shouldn’t be a competition on who has the most photos on Instagram and can get the most compliments on Instagram by some other people that don’t know anything about photography. You have to take a lot of pictures, you have to think about the pictures you take, you have to be able to explain why you’ve taken those pictures, and you have to be honest. And that’s the hardest part, you have to be honest with yourself. You have to compare yourself to the best photographers out there.

Don’t look at a magazine and say ‘oh, that’s a shitty picture in this magazine; my pictures are better than that one shitty picture in this magazine’ because you don’t know the circumstances the picture in the magazine was taken under. A lot of magazine photographs are lousy because you have to deal with publicists and egos, PR agents, restriction on time, lighting, and location.

So yeah, there is a lot of not so great photographs in magazines but you should compare yourself with, you know, two, three of the greatest photographers, whose work you really like. Think about really which work means the most to you rather than saying ‘I like Albert Watson, I like Mark Seliger, I like Avedon, I like Gursky.’

I like all of these people too but do I really love their work? Does their work really mean something to me? Out of all of them, only the Bechers’ work probably means something to me. I think it’s important not to have too many idols. Have a few idols, and then try to take pictures like them that hold up to their quality.

Out of that there will be something will come up that’s your own. No photographer is ever the same. You will walk away with something that will be yours that would look different.

So — oh god — I’m always so passionate and tell young photographers this, but you know, that’s really the way it is. Most young people are not willing to work hard enough.

PP: Well what, in your opinion, do you think makes a successful photographer?

MS: I think talent is only a part of the whole equation. I’m not going to name any names but I think there’s a lot of photographers out there that are not really that talented —

PP: Oh, come on! Give me a name.

MS: No, no, no!

They’re not really great photographers but they’re working a lot. And they’re making money. They’re making a fine living for themselves. Those kind of photographers are ultra driven. They really try hard, and they take an okay picture once in a while, or pretty good pictures.

I might be one of those, for what it’s worth. Time will tell which photographer still being talked about in twenty, thirty years from now. Only a few will be remembered. You have to always try to separate yourself from the photographers that just work really hard and that are just okay, and try to be better than you.

I have to push myself all the time. A lot of success in photography really comes from a very strong work ethic. Once you start getting jobs, once you develop your own style, things get a little bit easier. You can hire help, you even can afford other people to work for you, which makes your life a little bit easier.

But in the beginning you have to do everything yourself. Then there’s photographers who just have this great talent or maybe it’s their personality, or they do something that hasn’t been done before or they totally reinvent, like David LaChapelle, who revolutionized modern-day photography.

Terry Richardson, I think he is in the footsteps of [LaChapelle] a little bit in the sense that he really stood out with his style. He was really, really different when he started.

Annie [Leibovitz] invented modern-day magazine photography as we know it. Those people just have a lot of talent. But even then, they still have to work really hard.

Even though it has gotten so much harder, you have to have the drive and you have the self-reflection. Be honest about your own work. That’s the point that I always make.

I did a workshop once, and I had these young photo students show me these really bad-to-mediocre photographs, and they expected to be patted on the shoulder and being told how great their work is. No, I told them ‘it’s crap.’

They looked at me as if I was crazy. I’m like ‘well, have you ever looked at a photo book? Do you think your work is as good as the work in this photo book?’

Realistically, [your pictures] have to be as good as those pictures in those books. Or better! They have to be better in order to get a new book. If you did the same thing, it was already published!

I sound too bitter or something, I don’t know. I know all other photographers try to be more optimistic and more upbeat. I always sound so pessimistic when it comes to young photographers but it’s more me talking about my twenty-three year old than about the average photo student.

PP: Any upcoming projects?

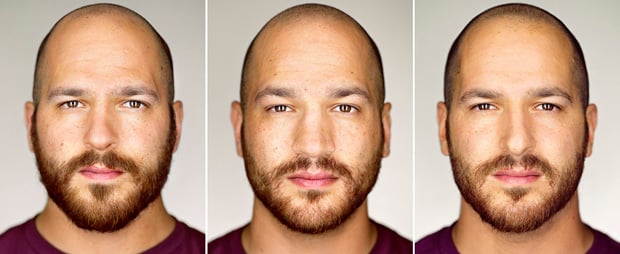

MS: I have this book, Identical, that just came out a few months ago. I don’t know if you’ve seen that with the twins and multiples photographed close-up style?

PP: I have seen that, yeah.

MS: And then next book is probably coming out next year, with more of my magazine work. Not my close-up images that I’ve taken during magazine assignments but what I call my ‘mental’ pictures — people in an environment. Then we’ll see what I do after that. Maybe another close-up book one day, in a couple of years, maybe after 20 years of doing them.

PP: Martin, thank you so very much for your time!

MS: Thank you!

I’d like to thank Martin Schoeller for taking time to speak to me from his New York City studio. You can learn more about Martin Schoeller and upcoming exhibitions and projects on his official website.

Image credits: Photographs by Martin Schoeller and used with permission. IMG_0414 by Darren and Brad