The Fascinating History of Leica Copies, From Braun to Zorki

![]()

Throughout photographic history, few cameras have had the kind of defining influence that can compare to the original Barnack Leica. It’s only natural that the industry of the time would react impulsively to the arrival of such a new, exciting, and innovative breed of camera – which is exactly what happened.

Others still used the Leica as a basis for creating entirely unique 35mm cameras that innovated on the formula Oskar Barnack invented. Ultimately, the “Leica Copy” label began fading as these descendants of the Barnack design grew increasingly distinct.

Today, let’s take a look at some of the most important Leica copies – from the literal counterfeits to the curious forgotten gems of days gone by.

The Very First Leicas and Their Imitators

To understand where Leica copies originated from, we need, of course, to first take a look at the Leica itself. The original Barnack Leica series began with the so-called Ur-Leica (or Pre-Leica), a prototype camera produced in limited batches during the 1910s.

The standardized Leica I was the first mass-produced equivalent of the design to introduce 24x36mm exposures on Kodak 135-format film to the masses. That came in 1925 – however, it wasn’t until the release of the improved Leica II in 1931 that Leica’s success really took off meteorically.

This is principally because of the second model’s addition of two key features: interchangeable lenses via the standardized M39 screw mount, and a built-in rangefinder housed in an integrated top plate that could automatically couple with all supported lenses.

It was also around this time, during the early-to-mid 1930s, that the first Leica copies began to emerge. This initially happened in two countries, the USSR and Japan, both of which would go on to become some of the most successful producers of Leica copies in the postwar period.

Introducing the FED, the Soviet Leica at a Worker’s Price

As early as 1934, a factory in Kharkiv, Ukraine (then part of the Ukrainian SSR in the Soviet Union) began production of a camera called FED.

Not much of this endeavor had a legacy of optics or mechanical manufacturing to back it up. The name FED came from the initials of Felix Edmundovich Dzerzhinsky, an early Bolshevik leader who helped found and lead the USSR’s first secret police force.

The FED factory itself was also hardly prepared for the kind of craftsmanship that making a precision 35mm rangefinder camera would require, at least not at the onset of the 30s. Starting out as a small labor commune for orphaned Ukrainian children, its operations were steadily expanded throughout the interwar period by its longtime leader, pedagogue Anton Makarenko.

First graduating to the manufacture of leather apparel and home-grade locks, then to power tools and more complex machinery, the FED factory was, at the turn of the decade, fashioning itself as one of the Soviet Union’s most promising up-and-coming domestic manufacturers.

At some point between the Leica II’s release and the year 1934, Soviet designers managed to reverse-engineer most of the mechanical design behind the Leica camera. How exactly this happened is still unclear – feel free to conjure up whatever 20th-century spy dramas come to your mind.

In any case, the Kharkiv labor comune’s management immediately saw some propaganda potential in this. What if Ukrainian children could put together a camera to rival the best the Germans had to offer, and sell it in numbers that Leitz could only dream of, marketing it to the average Soviet proletarian?

Suffice it to say that this was a lofty goal from the very beginning. Still, admirably, the original FED I of 1934 managed to faithfully replicate most of the Leica II not only in terms of looks but also in terms of function.

Its standard 50mm lens was a near-exact copy of the 50mm f/3.5 Leitz Elmar. The FED’s rangefinder specifications, the dimensions of its screw lens mount, and the focal-plane cloth shutter were also all faithful replicas of the original Leica design. Of course, corners were cut in many places, and the materials used don’t quite measure up either.

Still, at first glance and even when held in the hand, the FED was enough of a convincing copy of the Leica II that many lay people wouldn’t easily be able to tell the two apart. That it managed to not just follow the Leica in terms of feel and looks, but also in terms of performance (at least on paper, not taking reliability and accuracy into account), while being sold at a fraction of the price, made it a major milestone in Soviet photographic history.

Kwanon, the Unlikely Leica Copy From the East

Around the same time, Leica blueprints also made their way to Japan. Again, details about this are obscure and probably involved a lot of secrecy, some under-the-table transactions, and the kind of corporate espionage that we can only fantasize about today.

In any case, it wouldn’t be too long before a crop of Japanese Leica copies would make their way onto the scene. Unlike the Soviets’ first attempt, the FED, these cameras were not just branded as domestic propaganda tools, but explicitly made with export in mind.

One of the first Japanese Leicas was the Kwanon, which appeared in 1933. Like the FED, it was based on the Leica II model. And just like its Soviet counterpart, it’s a near-perfect copy, following every line of the spec sheet to the letter.

One major difference between the Kwanon and the FED is that the camera wasn’t all designed and built in-house. Kwanon was a small workshop at the time and didn’t have the capacity to produce their own glass.

Hence, for the Kwanon camera’s lens (which like the FED’s was an exact copy of the Leitz 50mm Elmar design), they contracted an optical shop by the name of Nippon Kogaku. That’s right, soon-to-be Nikon, which in fact landed one of their first commercial contracts designing that lens!

What’s even more interesting is that the company that designed the Kwanon would later evolve into what we now know as Canon – meaning that one of the very rare instances of collaboration between the two Japanese arch-rivals happened right at the very beginning of their respective histories, with Leica linking them together!

The End of World War II and The Leica Copy Invasion

Leica copies remained available throughout the pre-war years, with Japanese company Leotax becoming the second in its home country to market such a design in 1938. Its cameras were uniquely based on the higher-end Leica III model, with its additional front-mounted slow shutter speed dial.

However, Leica lookalikes would not really gain much steam until 1945. It was after the end of the war that Leica’s original patents for its cameras and lenses, along with countless other German pre-war patents across many industries, were voided by the French and American occupational forces.

This meant that all of a sudden, replicating the world’s signature 35mm rangefinder camera not only became permissible and no longer constituted counterfeit, but it was, in fact, free of charge.

Leitz themselves were also in another dilemma at the same time. Restarting production after the war proved difficult for them, as was the case with many other postwar German companies.

Leicas made in the immediate postwar years between 1945 and approximately 1950 gained a reputation for reduced build quality and issues in fit and finish compared to the earlier models – though prices remained just as high as before, in a domestic economy that was in tatters no less.

On top of that, Leitz was hardly innovating much on the original Leica II and III designs during this period, only offering the 1930s-spec ‘c’ models until a refresh in 1950. This changed basically overnight with the release of the Leica M3 in 1954. The M3 offered radical new features such as a swing-open back for easier film loading, a combined viewfinder-rangefinder eyepiece with parallax compensation, and streamlined ergonomics compared to its predecessors.

However, the M3 was not just even more expensive than prior Barnack Leicas. It also eschewed its M39 screw mount in favor of a new bayonet mount, which made upgrading a tall order for many cash-strapped photographers.

While the M3 and its later M-series siblings would go on to become some of the most lauded and widely successful rangefinders ever made, their inaccessibility also all but assured that the market for lower-end rangefinders would stay alive and well for quite some time.

As you can imagine, all these factors are what really opened up the floodgates for Leica competitors – copies, that is.

German Leica Lookalikes of the 1950s

Even in Leica’s home country of West Germany, competitors made use of the new environment created in 1945 to snatch a piece of Wetzlar’s cake.

Cameras like the Braun Paxette, the Franka Solida, or the later versions of the Kodak Retina were not ‘Leica copies’, at least not strictly speaking. They were all mostly based on existing, patented pre-war designs that didn’t stem from Leitz originally, and they shared a lot of mechanical differences with Barnack’s camera.

Still, it’s undeniable that the field of affordable, interchangeable-lens West German rangefinders expanded quite a lot during the 50s, reaching new heights and contesting Leica’s previous near-monopoly status.

More Soviet Rangefinders Emerge

The FED also picked up in terms of sales after 1945. Though the original Kharkiv factory remained closed for a few years following the end of the war due to damage sustained from German bombing raids, production quickly resumed at a different location near St. Petersburg.

Initially, not much changed about the design of the FED. Sales and production figures steadily increased while the factory made slight adjustments to the Leica design to improve reliability, such as small alterations to the shutter speeds and the addition of standard cable release threads.

Big changes would arrive in 1948. In that year, the FED assembly lines in Kharkiv were reopened, and production moved back to its original location. However, the KMZ factory in St. Petersburg did not want to cease production either, so they continued the assembly of FED bodies, now renamed Zorki.

For a few short years, FEDs and Zorkis were essentially the same cameras made with the same tooling and based on the same schematics. However, the release of all the aforementioned original German patents meant that both factories quickly got to work on more advanced improvements and design changes made possible by the better-quality, original documentation of the Leica design.

For the FED, the first major such revision arrived in 1955, one year after the release of Leica’s M3. The FED 2 improved on the original in countless ways that brought it more in line with the high end of the time: it featured flash synchronization, a very large rangefinder base of 67mm, a coincidence rangefinder that superimposed the rangefinder patch over the viewfinder image, and an improved loading mechanism where the back of the camera swung open as you inserted the film from the bottom.

To further distinguish it from its original inspiration, the FED 2 also sported an all-new design, which, while still clearly following in the Leica’s footsteps, made it look a lot less like an outright copy.

Over at Zorki, it was a similar story. With the heavily restyled Zorki 3 of 1951, which came with flash sync and a self-timer, the factory moved away from original Leica design cues just like FED, introducing a bold new look that was more ‘Leica-inspired’ rather than shamelessly adapted.

Sporting a unified rangefinder-viewfinder window, a 1/1000th of a second top shutter speed, and the addition of a Leica III-style slow speed wheel, as well as full viewfinder diopter adjustment, strap lugs, and a film loading system based on a removable back (no film lead trimming or bottom loading necessary), this Zorki was actually more advanced than the FED and all contemporary Leicas.

It even stood out in comparison to the M3, which upon the Zorki 3’s release was still a few years away! Of course, this was still a camera intended for the lower end of the market, and as such, the optical quality of its lenses, let alone the mechanical precision of its shutter, were not up to the same standards as those over at Wetzlar.

Still, it is a remarkable achievement for a lone Soviet factory to actually outpace Leica itself in terms of rangefinder innovation! Subsequent Zorkis and FEDs alike would not just become some of the Soviet Union’s best-selling cameras, but would even find success abroad in large numbers.

FOCA: Leica, Made in France

The release of the German prewar patents really came as a boon to the domestic industrial economies of plenty of European Allied countries, particularly France.

Under Charles de Gaulle’s postwar government, all German products were subject to very severe taxes and import duties, which made Leicas, for instance, all but unobtainable.

To circumvent this while giving the French optical industry a well-deserved shot of vigor, the government partnered with a veteran lens maker called OPL (Optique et Précision de Levallois) to produce a Leica rival purely for the French domestic market.

This would be called the Foca, quickly brought to release in 1945 and based partially on plans for a similar rangefinder that were already being studied before the war, but never made it into production.

Like the original Barnack Leica, the Foca came in three flavors: one basic version without a rangefinder, one with a rangefinder but without slow speeds, and a top-of-the-line model with a front dial for those extra shutter speeds.

These models were denoted with ‘stars’ displayed on a plaque on the camera’s body. The number of stars corresponded to each camera’s position in the lineup. There was also a fixed-lens derivative called the Focasport, intended for casual and amateur photographers. Improved upon in many revisions over the years, it became OPL’s top seller and was only canceled at the dawn of the 70s, as Japanese SLRs were taking over the budget camera market.

The first Foca cameras made headlines in France for their impressive build quality, home-grown engineering, and excellent lens lineup coupled with a unique 36mm screw mount. The camera’s distinctive broad body shape, which gave it fairly unique looks and a huge rangefinder base superior to the Leica’s, as well as its easy removable-back film loading system, won much praise. Long before Leica, the Foca put the rangefinder patch into the viewfinder window, with no need for separate eyepieces.

On the other hand, earlier versions had some deficiencies compared to the Leicas that inspired them. For instance, none of the initial Foca rangefinders of the 40s could couple to all of the camera’s available lenses – you had to use scale focus with anything that was above or below 50mm of focal length.

A later revision, named the Foca Universel, was made available in the 50s and solved all of these issues. With a fully coupled rangefinder, a new bayonet mount, and quicker lever winding, it became one of the most desirable cameras to have in France at the time.

The Foca would receive new, updated lenses and mechanical improvements all the way into the mid-60s. By that time, however, the original embargo on German goods that had prompted the Foca’s existence had already elapsed. This meant that late-year models, such as the Universel RC, were only ever produced in small numbers, with a lot of those going to the French Navy and Air Force.

Ironically, it is some of these rare Foca cameras, known for their build quality and unique design rivaling that of contemporary Leicas, that nowadays easily fetch the same prices as their Wetzlar counterparts on the used collector’s market!

The Golden Era of Japanese Rangefinder Cameras

While the Soviet Union’s FEDs and Zorkis gained in complexity and popularity and the Foca won over French shooters, the real market leader among Leica-style rangefinder cameras arguably turned out to be Japan, which aggressively exported their rangefinders during this time.

The Konica, made by the oldest Japanese optical company of them all, would be the first 35mm rangefinder camera built entirely using domestic parts, and the first to not be directly based on the Leica II or III. It still qualifies as a ‘Leica copy’ in the eyes of many camera historians, thanks to its very similar specifications save for the lack of interchangeable lenses.

Nonetheless, the Konica evolved very quickly after its initial release in 1947, gaining much more modern looks and revised ergonomics with the Konica II model of 1951.

The subsequent Konica III, released in 1956, would make even further advances in terms of build quality and features, with faster lenses and a unique film winding mechanism via a thumb lever on the front of the camera.

Younger camera companies, such as Minolta, also entered the 35mm fray with Leica-esque rangefinders built around cloth shutters and the M39 screw mount around the same time. These were never intended to be ‘copies’ per se, but they definitely depended on the original Leica for their success.

Kwanon, now going by Canon, continuously improved on their original pseudo-Leica II design, embellishing it with ever more advanced features and aesthetic changes.

Unlike the Soviets, however, companies like Canon attempted to move the Leica copy upmarket. Spending a lot of attention on fit, finish, and quality control, they rejected the approach of trying to win a value war by squeezing as many features into the camera at any cost.

Take a look, for example, at the Canon VT. As with the contemporary Soviet designs, Japanese Leicas really began to set themselves apart aesthetically and functionally from the Barnack Leicas more heavily post-1954, in large part thanks to the M3’s influence.

The VT, which came out in 1956, is a perfect example of that. Still sporting the M39 screw mount, but otherwise looking very much like a distinct rangefinder camera with only mild Leica cues, it was loaded with features and sold for pretty high prices in its home market.

Per standard, the VT came with a self-timer, a unified coincidence rangefinder-viewfinder with built-in adjustment for different focal lengths, and film loading via a swinging back. Curiously, the VT also included a bottom-mounted trigger for film winding, an arrangement that Leica itself also offered as an add-on, called the Leicavit.

Such trigger winding proved to be a popular trick for photojournalists of the 1950s to squeeze more frames per second out of their compact rangefinder while staying silent and discreet in the field.

Canon’s rangefinders of the mid-50s proved a real hit abroad, as did many other Japanese Leica copies. Many more affordable brands, like Nicca, Tanack, Tower, and the Leotax that I mentioned earlier, kept the prewar Leica II design while adding incremental mechanical improvements, like lever winding and flash sync.

Those lower-end, more conservative Leica copies proved an essential component of Japan’s rise in dominance over the consumer camera market. They also allowed plenty of beginner photographers to enter the hobby with a relatively affordable, yet high-quality camera that was compatible with the respected 39mm Leica screw mount, offering a clear upgrade path.

Reaching the Peak of Complexity

During the postwar economic boom, the Leica copy field became more intensely competitive. At the same time, the line that defined a ‘Leica copy’ as such got continuously blurrier as the years went by.

While Soviet examples did not advance considerably after 1955, changing aesthetically and ergonomically much more than mechanically, manufacturers from Japan and other countries were continuously stretching the envelope and developing more radical 35mm rangefinders.

Not all of these had interchangeable lenses – like the Konica. Not all of them used Leica-style cloth focal-plane shutters, such as the leaf-shuttered Minolta Hi-Matics, which featured built-in selenium meters long before there would ever be a metered-exposure Leica camera.

Though this signaled that change was on the way for cameras that could trace their origins back to the Leicas of the 30s, their story was not over yet. Many of them would reach the peak of their engineering complexity and technological advancement during this crucial time frame between the late 50s and mid-60s.

The Canon Grows Up

The last of the long line of Canon 35mm rangefinders would be the 7s, which came out as late as 1965. With its infamous 50mm f/0.95 lens and full compatibility with the M39 screw mount, it was a major showoff piece for the quickly growing Japanese brand, which was already executing its entry into the SLR segment at the time.

The Canon 7s matched every major technical feature of the Leica M3 (including parallax compensation) while also including an integrated light meter, clearly positioning itself as a direct competitor. While it never managed to outsell the Leica, it was nonetheless successful and boosted Canon’s reputation considerably.

The Non-Leica Leica Copy

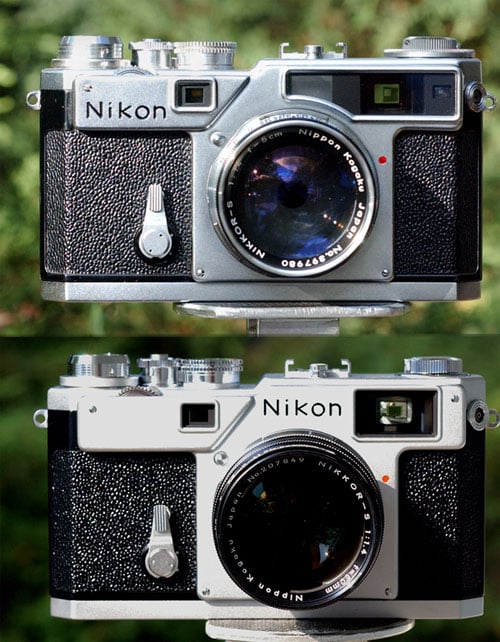

One camera series stood out in a field dominated by copies of pre-war Leicas and their descendants. The Nikon rangefinder camera, nowadays somewhat neglected in favor of the brand’s much more successful ‘F’ SLRs, first appeared in 1948 and was not actually based on voided Leica patents, but rather those of Contax.

Contax today is a forgotten brand itself, but during its prime in the 30s and 40s, its cameras were some of the most serious competition in the 35mm space that Leica ever faced.

All the Nikon rangefinder cameras, dubbed the Nikon S series, followed the Contax’s dimensions and ergonomic cues as well as the layout of its rangefinder. The Nikon lens mount, using a bayonet lock, was a near-copy of the Contax design as well.

The Nikon S evolved considerably during its roughly decade-and-a-half-long lifespan, gaining in features and build quality. The top-of-the-line final model, the SP, came with a highly advanced parallax-correcting viewfinder and sold for a high price during the early 60s, directly competing against the Canon 7s and Leica M3.

Nikon came out favorably in that war. Still, the company’s real claim to fame was not its advanced rangefinder bodies, but rather its lenses. Already when the S series was young and only selling in small numbers, Nikon lenses found great success among photojournalists.

When David Douglas Duncan presented his award-winning photo series captured during the Korean War with a Nikkor lens on a Leica body, it not only cemented the success of 35mm film as a medium. It also made sure that Nikon would end up becoming one of the biggest names in photography over the coming decades.

With that in mind, it’s no wonder that when the company decided to move onto SLRs, they used the basic body shell and ergonomics of the SP to do so. Put a Nikon SP and an F side-by-side, and you’ll find their top plate dials and the bottom of each camera are near-identical!

Losing Steam

At some point towards the end of the 1960s, the ‘Leica copy’ moniker began falling out of use.

The only rangefinder cameras still based on Oskar Barnack’s original designs were the various Soviet models, such as the late Zorki 4 (exported by the literal millions, actually becoming the best-selling Russian rangefinder ever) and the FED 5, a metered-manual design that actually stayed in production until the fall of the Iron Curtain in 1990.

Despite their modernized looks, the Barnack mechanical heritage of these cameras gave the Soviet Leica copies reputations of dinosaurs, holdovers from a past era, and symbols of the lack of innovation during the Soviet Union’s latter years.

At the same time, Japan, which had emerged as the dominant maker of Leica-esque 35mm rangefinders, moved on to greener pastures. Sales of Japanese SLRs exploded during the 60s, displacing the market that had previously belonged to rangefinder systems.

Compact cameras – lightweight, fixed-lens leaf-shutter rangefinders with built-in light meters – offered a more affordable entry point into the photographic hobby while being more advanced than their screw-mount forebears and more precise and easier to produce at the same time.

It was all these factors combined that essentially assured the complete demise of the Leica copy sometime by 1970.

Leica Copies Today

Today, Leica copies remain a fixture of the used film camera market. Many collectors and photographers alike are especially drawn to the later, high-end examples of the trend – Nikon’s S2, S3, and SP cameras, Canon’s P and 7 models, and other comparable rangefinders.

Relatively unique outliers, such as the Minolta 35 or the Foca, also remain valuable examples of an important era of photographic history for some.

Yet others see Leica copies as a cost-saving opportunity to get into the M39 screw mount system. Just as in their prime, Barnack Leicas sell for quite a premium, but as you can use their stunning lenses on any of their countless copies, shrewd photographers can get the very same image quality and most of the traditional Leica user experience for far less of an investment.

Some of the very early Leica copies, like Leotax, Chiyoda, and Kwanon, as well as the early Soviet examples like some FEDs and the very first Zorkis, are so close to the originals in both specs and quality that many amateur photographers would be hard-pressed to justify the price difference, at least at first blush.

This can be both a blessing and a curse. Plenty of less-than-honest sellers have abused the overwhelming similarities between these early copies and their much more valuable Wetzlar-made counterparts, modifying Leica copies ever so slightly to then pass them off as the real deal at very inflated prices.

This has caused an environment of uncertainty, where Leica collectors have gotten used to double and triple-checking any listing of something purporting to be an early Leica II or III body. On the other hand, Leica copies now are doing much of the same thing that they managed in their prime: connecting a younger generation of shutterbugs with the joys of fully mechanical 35mm rangefinders at a discount.