Wildlife Magazine Comes Close to Publishing AI Image of Bear and Elk

In a world where AI can imitate high-quality photography, nature magazine editors must be more vigilant than ever before — as is the case for one publication that came close to putting an AI-generated picture on its front cover.

Paul Queneau, editor-in-chief of Montana Outdoors, the print magazine for Montana Fish, Wildlife and Parks, was looking at a photo of a grizzly bear standing over an elk that had been sent to him from a photographer in Bozeman that he was considering running. But something wasn’t right.

“It had these weird, golden eyes,” Queneau tells Mountain Journal. “I remember thinking, I can’t make sense of the lighting in this image. And it was the front-runner for the cover.”

Queneau emailed the photographer and received a “snarky” reply, implying the editor simply didn’t appreciate great light. As the editorial team looked closer at the image, it became clear that it wasn’t real: the space between individual strands of elk hair revealed a different background, and the elk’s eyes were reflecting light from the front, even though the ‘Sun’ is clearly meant to be behind the two animals.

“I have a pretty good eye for it, if something’s not quite right in a photo,” says Queneau. “But the truth of the matter is it’s getting harder to tell.”

Queneau relies on an “honor system”, building relationships with photographers who he can trust. Nevertheless, when he was assembling the 45th annual January photo issue of Montana Outdoors — the most popular edition of the year — he put out a clear warning to contributors.

“We put in bold text: we don’t accept images manipulated with artificial intelligence,” Queneau tells Mountain Journal. “We hope people will be honest. But my fear is we’re getting to the point where we won’t be able to see if it’s a fake shot or not.”

An unscrupulous ‘photographer’ trying to fool a magazine editor is not good, but everyone is now swimming in a tide of AI imagery, or slop, as many call it. It’s something that regular Mountain Journal contributor Ben Bluhm has noticed on social media.

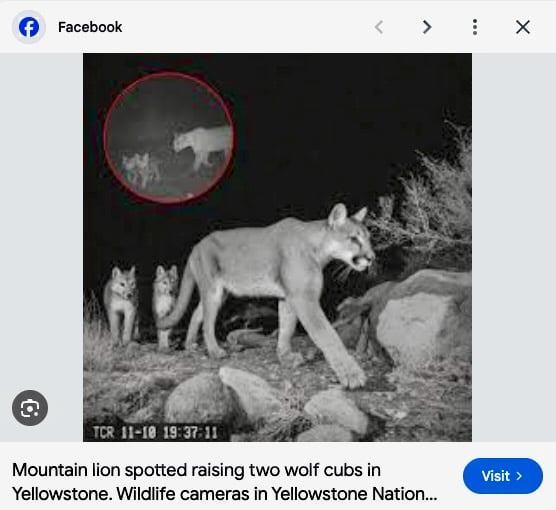

“This post had this whole story about crazy behavior captured in Yellowstone: a mountain lion raising two wolves,” says the Idaho-based photographer. “It was really sad that it went insanely viral. It had 45,000 likes, 1,600 comments, and 5,500 shares. So many people believed it.”

Mountain Journal covers the environmental in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem and beyond. Featuring stories about wildlife connectivity and disease, water, wildfire, and growth — the intersection of humans and nature.

“We work with passionate, dependable nature photographers who hold their craft to the highest standards,” MoJo editor Joseph T. O’Connor tells PetaPixel. “On occasion, I will get their professional opinions about whether a photograph is real or not. We also use certain programs like Image Whisperer that can help identify fabricated photography, and we don’t use game farm imagery. AI photos depicting wildlife and nature is a growing problem. There’s no shortage of misleading and fake images floating around, and that is becoming increasingly problematic.”

One of those dependable photographers and Mountain Journal contributor is Charlie Lansche.

“I can sleep well at night knowing that the images I sold are real, actual photos,” Lansche says. “The amount of bull****, fake photography being passed off as real, is frankly disgusting. I can’t even tell the difference now.”

Lansche actually captured a real photo of a grizzly bear standing over a bull elk. Last year, he found the bull elk trapped in a mud bog on the eastern edge of Yellowstone National Park. After it died, he returned for five consecutive days to see what would happen to the carcass. He posted a photo of a grizzly bear with its paw on the dead elk’s antler, titling it “Claiming the Prize.” Social media commenters quickly accused him of “total AI.”

“I almost didn’t share it,” he says. “It’s not the greatest photo. It’s shot at long distance, and it isn’t my typical image. But there’s a story behind it.”

Over the days Lansche spent watching the scene, several different bears tried to pull it out of the muck. First was a young sow. Then an older sow kicked the younger one off, but it didn’t have the strength to pull it out. On day five, a seldom-seen bear local wildlife photographers know as Big Red came in full-trot, nose in the air, running to the scent of that carcass stuck in the mud.

“He got on that thing like a dog on a chew toy, and he heaved and huffed and puffed and dragged it out of the muck,” Lansche says. “Then he pulled it 30 or 40 yards away and started feeding on it. He scared off every other bear that came near.”

For Lansche, the experience recalls the old National Geographic photographer’s maxim: “F/8 and be there.”

“Sometimes nature delivers something that’s jaw-dropping,” Lansche concludes. “We live for those moments. Whether you come back with the cover shot or something mind-boggling isn’t the be-all/end-all. Watching the sunrise, anticipating where the elk might emerge, showing up with friends — for us photographers driven by soul and feeling and emotion and wildlife in natural places, you won’t cross that line.”