A Largely Unknown 1970s Photo Project Captured Over 80,000 Images of American Pollution

![]()

Not long after President Richard Nixon signed the act creating the Environmental Protection Agency in 1970, the EPA launched a 50-state effort to document pollution. Photographers hired by the federal government took more than 80,000 images.

PetaPixel has reported on this project before, but a half-century later, a new feature-length documentary film delivers even more information and piques additional interest in this largely forgotten archive. The film, “The Documerica Project — Environmental destruction in 80,000 photos,” showcases aging photographers recalling their documentary work for the EPA in the 1970s.

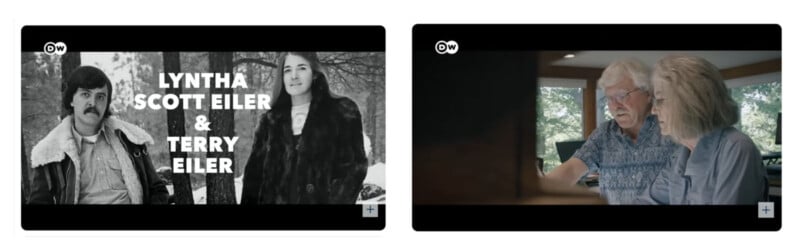

Photographers shown in the film include Boyd Norton, Arthur Tress, Bill Gillette (1932-2021), Lyntha and Terry Eiler, and Pulitzer Prize winner John H. White (from an interview conducted in 2012).

EPA History

The 1969 Santa Barbara oil spill in California and the Cuyahoga River fire in Ohio helped prompt the creation of the Environmental Protection Agency in 1970. EPA’s first administrator was William D. Ruckleshaus, who hired writer/photo editor Gifford D. Hampshire in EPA’s communication office.

Ruckleshaus authorized Hampshire to develop Project Documerica to create a visual baseline of environmental challenges facing America. More than 120 photographers contributed to the project, said Hampshire’s obituary.

The model for Documerica was government photography in the Great Depression, commissioned by Roy Stryker of the Farm Security Administration (FSA).

Documerica

The broad, ambitious goal of the Documerica Project was to make a record of pollution and its human impact, help motivate action, and eventually document progress and solutions.

Photographers Terry and Lyntha (Scott) Eiler were assigned to northern Arizona. Terry Eiler recalls that smoke plumes from a coal-burning plant were visible from space.

Documerica was “the before pictures,” says Lyntha Scott Eiler, intended to show pollution before it was cleaned up.

By 1977, the project ended, and interest fizzled. The Arab Oil Embargo, launched in 1973 to protest U.S. support for Israel in the Yom Kippur War, caused price spikes and fuel shortages. Political support for jobs superseded an earlier focus on environmental issues, says the film about the Documerica Project.

Public attention was also engaged on the Vietnam War and civil rights.

As PetaPixel previously reported, many images from the 1970s-era EPA photo project are available via the National Archives and EPA.

The Atlantic published 46 Documerica photos in 2011 and ABC posted a report in 2017. The headline on a 2013 article published by Fast Company was: “Gorgeous Vintage Photographs Of America In The 1970s, Captured By The EPA.”

A 2009 dissertation by Barbara Lynn Shubinski at the University of Iowa said the Documerica Project pointed to broader issues beyond pollution. Images of architecture and social surroundings, she wrote, “evince the era’s deep-seated anxieties about fragmentation, degradation, suburban sprawl, urban decline, and proliferating car culture.”

Indeed, the Documerica portfolio extended beyond pollution. For example, photographer Cornelius M. Keyes documented farm-labor leader Cesar Chavez in 1972. John H. White photographed singer Isaac Hayes at the 1973 Black Expo in Chicago.

Film Festivals and German TV

The contemporary feature-length film about the Documerica Project created buzz at festivals, premiering in Australia on opening night at Environmental Film Festival 2025 and winning the history award at Cinema Verde Environmental Film Festival in Florida.

The film was written and directed by French photographer Pierre-Francois Didek. German broadcaster Deutsche Welle (DW) recently featured and reported on Documerica.

As the film ends and its credits appear, viewers hear satirist songwriter Tom Lehrer singing his tune “Pollution,” which was released in 1965:

You will find it very pretty

Just two things of which you must beware

Don’t drink the water and don’t breathe the air!

In July, Lehrer’s obituary in The New York Times included this paragraph about his visibility: “By 1981 he had fallen so far off the cultural radar that, he told The Harvard Crimson, some people thought he was dead. (“I was hoping the rumors would cut down on the junk mail,” he said.)

Like the Documerica Project, songwriter Lehrer had talent and garnered attention, but did not hold a top-of-mind grip on the national consciousness.

Image credits: Photos from Documerica, individual photographers are credited in the captions. Header photo credits: Marc St. Gil (left) and Jack Corn (right).

About the author: Ken Klein lives in Silver Spring, Maryland; he is retired after a career in politics, lobbying, and media including The Associated Press and Gannett in Florida. Klein is an alumnus of Ohio University and a member of the Dean’s Advisory Council of the Scripps College of Communication. Professionally, he has worked for Fort Myers News-Press (Gannett), The Associated Press (Tallahassee), Senator Bob Graham, and the Outdoor Advertising Association of America (OAAA).