There’s a Problem With Photographers’ Obsession With The Golden Ratio

![]()

Claims made about the golden ratio in nature are often overstated or romanticized. In fact, it is more often a useful model than it is a universal law,

It is often suggested that the golden ratio (≈1.618) is found everywhere in nature. However, nature favors efficiency and adaptability over strict mathematical beauty. Although it does appear in some natural patterns and structures, it is often in approximate rather than exact ways.

Many artists throughout history applied the golden ratio to their paintings. Photographers adopted it too. Although he is most well-known for “The Decisive Moment,” Henri Cartier Bresson was obsessed with composition, including the golden ratio. Deeply interested in geometry and classical composition techniques, Cartier-Bresson studied dynamic symmetry and the golden ratio extensively, analyzing his own photographs for compositional harmony. He endeavoured to internalize these principles so thoroughly that he could apply them instinctively when taking photos.

What is the Golden Ratio?

The golden ratio is a mathematical figure derived from the Fibonacci sequence. That is a series of numbers where each number is the sum of the two preceding ones, beginning with 0 and 1.

You start with 0 + 1 = 1.

Then you add the last two numbers again: 1 + 1 = 2.

Then you continue: 1 + 2 = 3, 2 + 3 = 5, 3 + 5 = 8, and so on.

Therefore, the sequence goes: 0, 1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 21, 34, 55, …

As the sequence grows, the ratio between two consecutive numbers gets ever closer to 1:1.618, which is known as the golden ratio.

55 ÷ 38 = 1.6176,

89 ÷ 55 = 1.61818 …

4181÷ 2584 = 1.61803

Why is it Significant

![]()

The golden spiral derives its shape from increasing areas that correspond with the Fibonacci Sequence. The shape is sometimes found in nature. The sequence is found in nature. For example, famously, some spiral shells (like those of the nautilus) resemble the golden spiral, though they don’t match it perfectly. In phyllotaxis, the arrangement of leaves, seeds, or petals in plants (e.g., sunflower seed spirals, pinecones, artichokes) often follows a pattern that matches the Fibonacci sequence, and thus approximates the golden ratio.

The relationship is also claimed elsewhere in nature. Spiral shapes in whirlpools, hurricanes, and galaxies may resemble golden spirals, but again, there is no precise mathematical relationship. However, although some studies suggest that golden ratio-like proportions are found in animals, it is by no means universal.

![]()

What Has Da Vinci Got To Do With It?

The golden ratio is often associated with Leonardo Da Vinci; the plot of Dan Brown’s novel, The Da Vinci Code, relies on it as a plot device. However, it’s probably an overstated factor.

Vitruvius, full name Marcus Vitruvius Pollio, was a Roman architect, engineer, and author. He lived during the 1st century BCE, born around 80–70 BCE, and was active until around 15 BCE.

While serving as a military engineer under Julius Caesar, he specialized in siege engines, including the ballista and scorpion. He also traveled extensively across the Roman world, through Greece, Asia, North Africa, and Gaul, gaining firsthand knowledge of architecture and engineering. His ten-book treatise, De Architectura, is the only complete architectural text surviving from antiquity. It covers a wide range of topics, including architecture, engineering, city planning, acoustics, hydraulics, astronomy, and medicine.

Vitruvius introduced the three architectural principles: Firmitas (strength), Utilitas (functionality), and Venustas (beauty).

During the Renaissance, Leon Battista Alberti revived his work. Vitruvius’ writings then became foundational texts for architects such as Palladio, Michelangelo, and Bramante. It later famously inspired Leonardo da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man, which was based on Vitruvius’s descriptions of ideal human proportions.

According to Vitruvius, the human body is a microcosm of geometric perfection. He believed that the human body’s proportions could be used to design buildings that were well-balanced and harmonious. Contrary to popular belief, and some of the textbooks I own, those proportions he used did not correspond with the golden ratio.

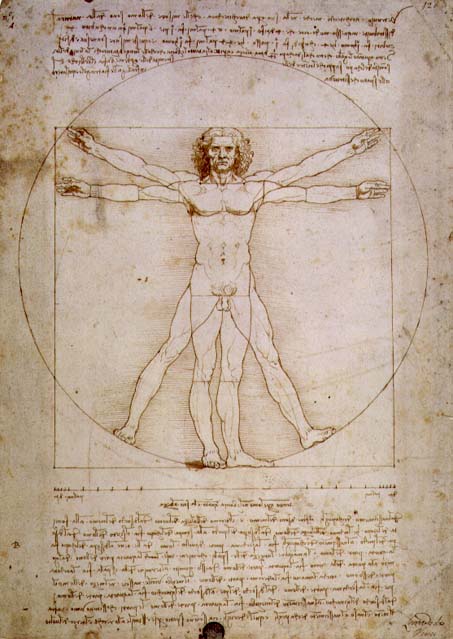

It’s a popular myth that is often repeated in books on composition that Leonardo da Vinci used the Golden Ratio to create the Vitruvian Man, distorting the body to fit it. But that’s not entirely accurate. The drawing was based on Vitruvius’s writings, which described ideal human proportions using simple fractions.

As you can see above, Da Vinci’s drawing depicts a man in two superimposed positions. In one position, the figure is inscribed within a circle, and in the other, he is within a square. Its purpose is to symbolize the unity of art, science, and nature, as proposed by Vitruvius. The picture shows that the span of the arms equals the height of the man, the navel is the center of the circle, and the body fits perfectly into both a square and a circle. The face is 1/10th of the total height, while the head is 1/8th, and the foot is 1/6th.

However, some analyses indicate that certain body parts in the drawing do align with the golden ratio. Nevertheless, the overall geometry (e.g., the ratio of the circle’s radius to the square’s side) does not match the golden ratio at all. The ratio used is around 0.608, not the irrational 0.618, which is the reciprocal of the golden ratio.

So, DaVinci was more focused on Vitruvian symmetry and classical proportions. While some golden ratio relationships can be observed in that drawing, they are likely coincidental or secondary, rather than the primary design principle.

This Vitruvian symmetry is not about the golden ratio, but rather about integer-based proportions that reflect classical ideals of beauty and balance. Indeed, Vitruvius neither mentions nor advocates the golden ratio in his writings.

Although Da Vinci was familiar with the golden ratio, it wasn’t the only driving force behind his compositions, as is often suggested.

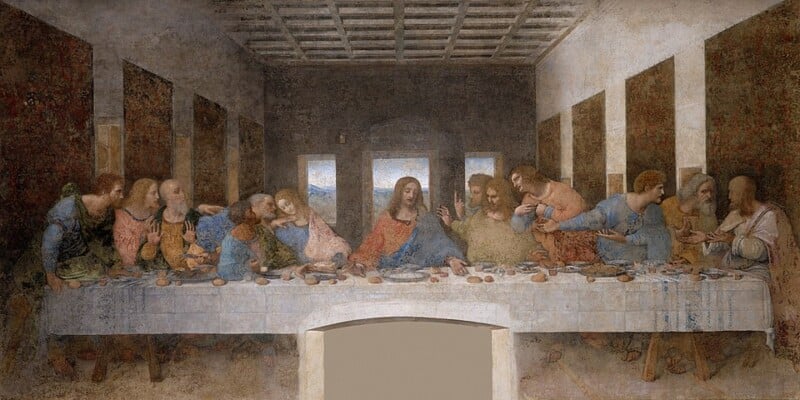

Nevertheless, he did illustrate Luca Pacioli’s book, “De Divina Proportione” (1497–1509). That book explored the golden ratio in geometry, art, and architecture. He also applied the golden ratio in several of his paintings. Those included “The Annunciation” (c. 1472–1473), where the golden ratio appears in architectural elements and the overall composition. Furthermore, in “The Last Supper” (c. 1494–1498), the golden ratio is evident in both the layout and positioning of the figures. Though debated, some suggest that the golden ratio also exists in the facial features of the “Mona Lisa” (c. 1503–1506).

The Golden Ratio in Photography

Similarly, later artists used the golden ratio in their work. Turner’s Calais Pier and The Fighting Temeraire are prime examples.

The work of French Artist Georges Seurat also strongly featured the golden ratio. Interestingly, his work greatly inspired André Lhote, who taught art to Henri Cartier-Bresson. Cartier-Bresson had a deep passion for geometry in composition, which he described as a source of both intellectual and sensuous pleasure. He emphasized the importance of internalizing compositional principles, such as the Golden Ratio.

Significantly, he believed that by studying geometry, the golden ratio, and other forms of dynamic symmetry, they could ultimately be applied instinctively when composing the shot. There is no denying the greatness of Cartier-Bresson’s photography, so maybe he had a point.

There’s an important lesson here: exploring compositional techniques helps embed them in our subconscious mind, allowing us to apply them without conscious thought.

In Conclusion

The golden ratio is a valid and valuable tool for composing a photograph. Indeed, it appears as a possible compositional overlay guide in Lightroom and other software. However, it isn’t some magic principle that will make your photos great. Nor is it the right solution for every photo. It’s just one of a myriad of compositional tools that you can employ if it is right for a particular photo. There are a host of other techniques that you can use as well, and whether they work or not is entirely subjective.

![]()

So, although it’s essential to learn this and other compositional approaches, you don’t have to follow any single one religiously.