Researchers Uncover the Secret Glowing World of Biofluorescent Birds-of-Paradise

![]()

A team of researchers investigating biofluorescence in birds-of-paradise species uncovered fascinating insights into avian vision, fluorescent feathers, and biological evolution and captured some fantastic glowing photos in the process.

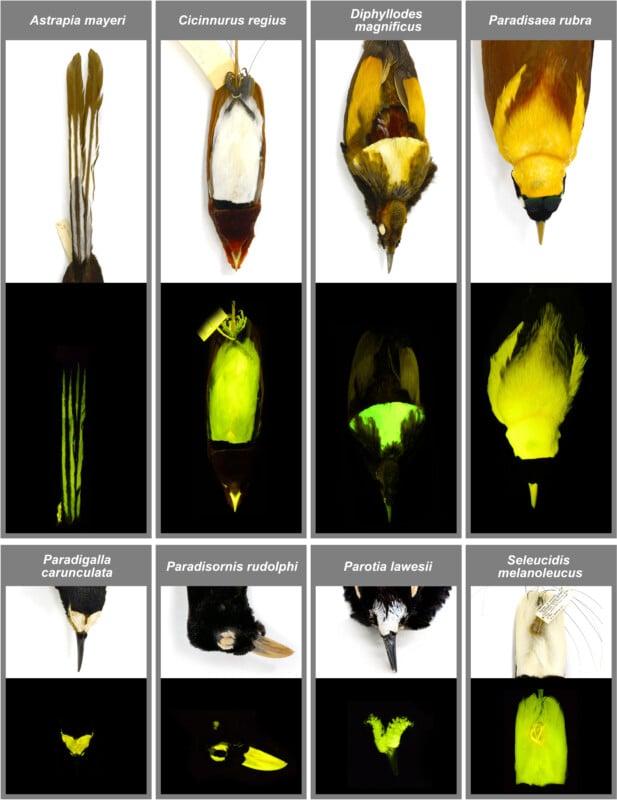

Researchers Rene P. Martin, Emily M. Carr, and John S. Sparks published their research earlier this month in the journal Royal Society Open Science, detailing the study of all 45 subspecies of birds-of-paradise. Of these 45 species of Paradisaeidae, which are known for the male’s elaborate feather morphology, coloration, and mating displays, 37 showed biofluorescence upon investigation, including all core members of the species.

Although the degree and location of biofluorescence varies by species, it occurs on the plumage and skin relevant to mating displays, leading the researchers to propose that the biofluorescence functions as a signal during courtship and mating displays.

Birds-of-paradise, like other avian species, have tetrachromatic color vision. They have four single-cone cell types in their photoreceptor system — eyes — enabling them to see a wider range of light. Humans have trichromatic vision and can typically see wavelengths of light from about 380 to 700 nanometers. Tetrachromats, like birds of paradise, however, have a fourth cone beyond what people have that is sensitive to near-ultraviolet light (300 nanometers).

While avian courtship and mating displays are a hot area of study for biologists and evolutionary biologists, relatively little research concerns the role fluorescent light may play in bird behavior. Thanks to their tetrachromatic vision, birds-of-paradise and other avians can see ultraviolet spectra, which is fascinating enough. However, birds’ eyes also include special oil droplets that narrow the spectral sensitivity of each cone. While this selectivity varies across the avian landscape, some birds can filter light to see biofluorescence better.

“Biofluorescence occurs when an organism absorbs high-energy wavelengths of light (UV, violet and blue) and re-emits them at lower-energy wavelengths (greens, yellows, oranges and reds),” the researchers explain.

Naturally, studying how vision impacts species with tetrachromatic photoreceptors is exceptionally difficult for people — it is impossible to imagine precisely how animals can see with a wider range of color than people, although it is simple to imagine how dichromatic animals like dogs see the world (with much less color). The researchers employed specialized camera and lighting equipment to get a firmer grasp.

Armed with a Nikon D800 DSLR, a Nikon AF-S Nikkor 105mm f/2.8 G ED macro lens, and a pair of Nikon SB-910 flashes covered with blue interference bandpass excitation filters to restrict imaging to specific wavelengths (approximately 500 nanometers), the researchers captured images that show the biofluorescent regions of birds-of-paradise plumage and skin. They used specimens from the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH) in New York, which has male and female specimens from all birds-of-paradise species, save for one species where only a male specimen was available.

![]()

The team edited the images slightly to remove dust particles, background debris, and edit out the cotton visible in specimen eye sockets, as the cotton has fluorophores.

“The images are vibrant green because we effectively cut out wavelengths under 500 nanometers (blues, purples). Green/green-yellow is the brightest color that these biofluorescent patches reemit, thus that’s what the camera is picking up,” Dr. Rene Martin tells PetaPixel.

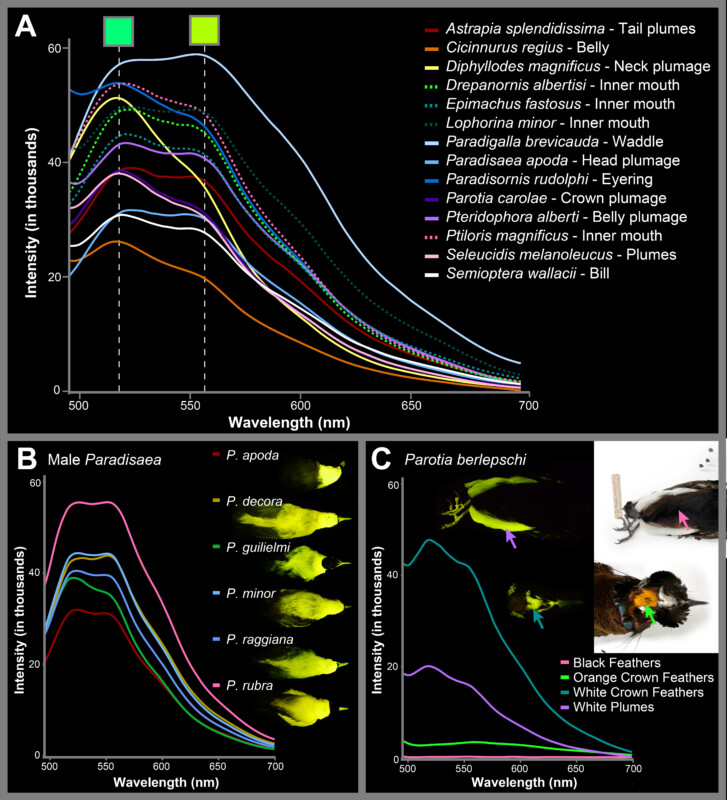

What’s especially fascinating about birds-of-paradise is that the researchers believe they have spectral sensitivities primarily within the visible spectrum. This contrasts with many other species, which visualize spectra in the ultraviolet range.

![]()

“Birds-of-paradise are inferred to have spectral sensitivities in the VS spectrum, with VS cone type peaks at 402−426 nm and with additional cone peaks at approximately 480 nm (short-wavelength sensitive (SWS) cone type), 540 nm (middle-wavelength sensitive (MWS) cone type) and approximately 610 nm (long-wavelength sensitive (LWS) cone type). This is unlike many UVS-sensitive bird species that can visualize light peaks in the UV range around 355−380 nm,” the paper explains.

They find that ultraviolet light excitation causes the intense biofluorescence seen in the images, peaking in the 480 to 530-nanometer range. This corresponds to the spectral sensitivity in the cones of the birds-of-paradise.

Essentially, birds-of-paradise, through fluorescent skin and plumage, enhance their flashiness to potential mates by converting high-energy ultraviolet and blue light, which their eyes are actually not very sensitive to, and re-emitting it at specific wavelengths where their eyes are much more sensitive.

In contrast to the rest of its appearance and, importantly, its habitat, birds-of-paradise are basically glow, at least to other birds-of-paradise. As if their amazing dances weren’t enough!

Image credits: Rene P. Martin. The research paper, ‘Does biofluorescence enhance visual signals in birds-of-paradise?‘ was published in The Royal Society Publishing and is authored by Martin, Emily M. Carr, and John S. Sparks.