Hubble Photographs Record-Setting Bullseye Galaxy and Galactic ‘Arrow’ That Made Its Rings

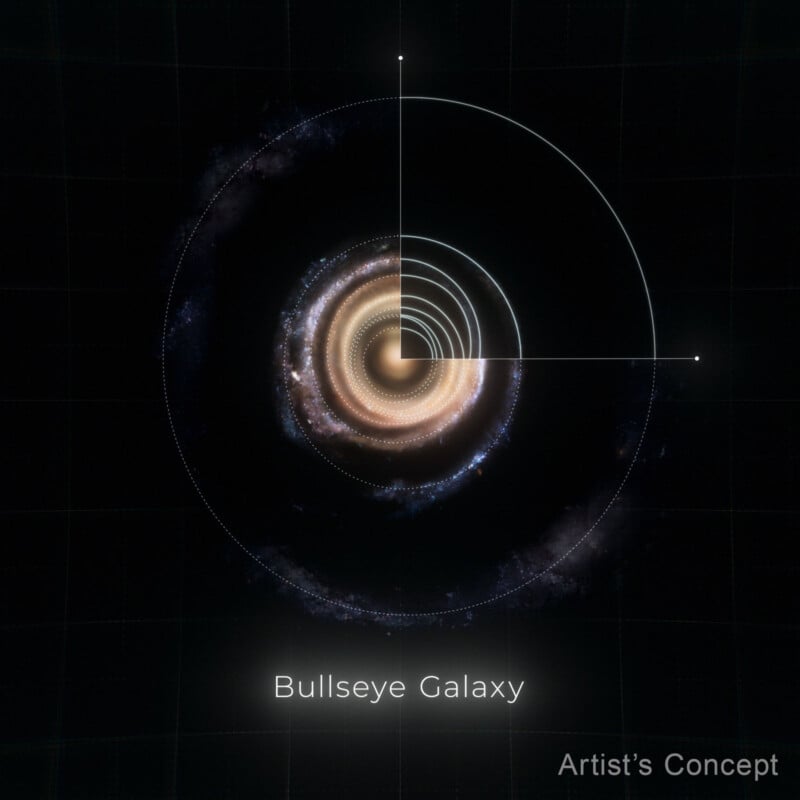

Scientists using the Hubble Space Telescope investigated a goliath galaxy, LEDA 1313424. Nicknamed the “Bullseye,” this galaxy features nine rings, many more than any other known galaxy. A stunning new image shows many never-before-seen details, delighting astronomers and regular viewers alike.

Previous observations of other galaxies typically find a maximum of two or three rings. Hence, LEDA 1313424’s nine — eight as seen by Hubble and a ninth observed by the W.M. Keck Observatory in Hawaii — are really incredible.

“This was a serendipitous discovery,” says Imad Pasha, the lead researcher and a doctoral student at Yale University in Connecticut.

“I was looking at a ground-based imaging survey and when I saw a galaxy with several clear rings, I was immediately drawn to it. I had to stop to investigate it.”

Follow-up observations shed additional light on other incredible features of the Bullseye galaxy, including a blue dwarf galaxy, seen center-left in the image, that “traveled like a dart” through the core of Bullseye galaxy about 50 million years ago, which left rings in its wake, “like ripples in a pond,” NASA says. The two galaxies remain linked today through a thin trail of gas, although about 130,000 light-years currently separate the galaxies.

“We’re catching the Bullseye at a very special moment in time,” explains Pieter G. van Dokkum, a co-author of the new study and a professor at Yale. “There’s a very narrow window after the impact when a galaxy like this would have so many rings.”

NASA says that galaxies “collide or barely miss one another” often on a cosmic timescale, but it’s exceedingly unusual for one to go through the center of another. The Milky Way and Andromeda galaxies are expected to collide in 4.5 billion years, for example, although any direct collision of stars is unlikely.

Another remarkable aspect of the Bullseye galaxy is its size. The Milky Way galaxy is approximately 100,000 light-years in diameter, while the Bullseye galaxy is about two and a half times larger — 250,000 light-years across.

Pasha also found that LEDA 1313424’s rings appeared to move outward as predicted by long-standing models.

“That theory was developed for the day that someone saw so many rings,” says Professor van Dokkum. “It is immensely gratifying to confirm this long-standing prediction with the Bullseye galaxy.”

Although the rings appear evenly spaced from Hubble’s perspective, scientists say the picture would look quite different if Hubble could view the Bullseye galaxy from above.

“If we were to look down at the galaxy directly, the rings would look circular, with rings bunched up at the center and gradually becoming more spaced out the farther out they are,” Pasha explains.

Researchers believe the first two rings in the Bullseye galaxy formed “quickly” and that additional ring formation was likely more staggered since the blue dwarf galaxy’s flyby through the center of the galaxy impacted the first rings much more.

There is much more research to be done concerning the Bullseye galaxy as scientists work to understand precisely how the galaxy’s gas and dust have changed over time and to understand which stars existed before the blue dwarf flew through it. The research will also aid in developing new models that better predict galactic behavior over cosmic timescales.

While finding LEDA 1313424 was a “chance finding,” scientists expect to find more galaxies like this soon once NASA’s Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope begins its scientific operations. The telescope is expected to launch in 2027.

“Once NASA’s Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope begins science operations, interesting objects will pop out much more easily,” van Dokkum says. “We will learn how rare these spectacular events really are.”

Image credits: NASA, ESA, Imad Pasha (Yale), Pieter van Dokkum (Yale). Illustrations by NASA, ESA, Ralf Crawford (STScI). The related research paper was published this week in ‘The Astrophysical Journal Letters.’