To Share or Not to Share: Deciding on Which Photos to Release to the World

At one point during his career, the late film photographer Jerry Uelsmann gave a slide presentation to a large audience of photography students, showing all the photographs he had made that year.

Another photography legend, Ansel Adams, is known for saying, “Twelve significant photographs in any one year is a good crop.” Many photographers use this in their defense for not releasing as much work as others, but I don’t think that is the point Adams was trying to make. While I believe there is no “right” number of photographs we should release each year, I think that if Adams were alive today, working with digital cameras and modern software (and more efficient means of travel), he would surely create more than just a dozen portfolio images per year.

The main point that both Uelsmann and Adams were making has nothing to do with quantity. They were both stressing that as artists, instead of publishing every piece we make, we must practice curation and release only the images that we deem “significant.”

It makes me wonder: How many paintings did Van Gogh and Picasso paint over or throw away during their lifetimes? Perhaps some of them were even more stunning than the ones we know today. Maybe some of these destroyed pieces would have gotten the artists more recognition or even changed the trajectory of their lives. We will never know. But, ultimately, I am glad that we cannot see every single doodle, sketch, or inadequate painting they made.

As a photographer, I’m grateful I don’t have to share something if I don’t want to. If I were forced to publicly display everything I make, I would quit photography, as I would have no room to experiment and play around, working on ideas in private over the course of years before I ever present them.

So how can we decide which images should be released and which do not deserve to be in our portfolio? We can base our criteria on many factors, but I strongly feel that they should always be rooted in our own personal beliefs. The criteria must be our own, coming from within, not the public’s or anyone else’s. Once you consider how others will perceive your work more than how it makes you feel, you are creating your art with a committee and trying to come to a group consensus. No great art was ever made this way.

First Drafts

Many of the images I have “thrown out” have been unsuccessful attempts at ideas that I have had. Sometimes while in the field, certain subject matter I encounter in the field will inspire me, but it usually takes several attempts — even over the course of years — before I feel that I have fully reached the potential of my vision. Rather than release every rendition of my idea as I make it, I wait until I feel I have succeeded in executing my vision before sharing the work with the world. Releasing inferior versions of an image will only dilute its impact once the best version eventually comes to fruition. It would be like a writer publishing every single draft of a book leading up to the release of the final edition.

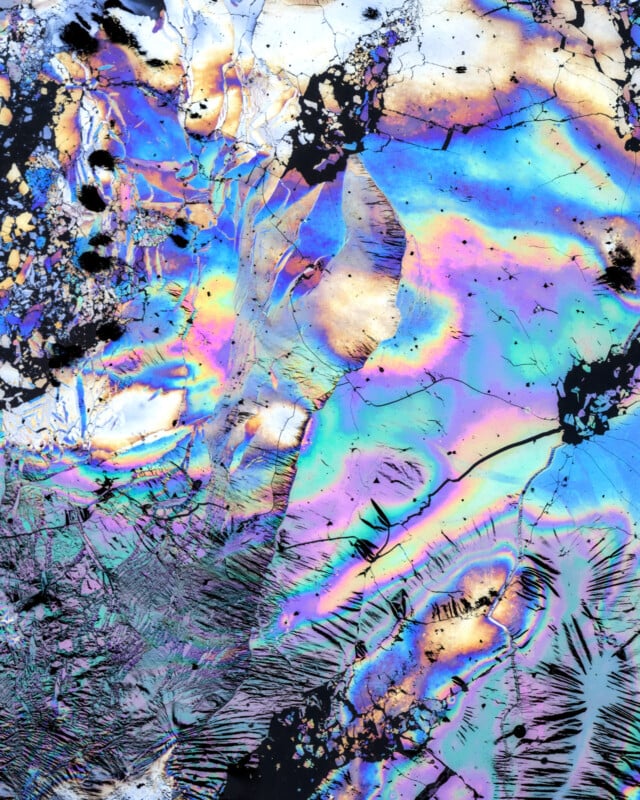

One example is when I found naturally occurring oils in a desert canyon circa 2015. I was captivated by the subject matter and was excited about making a photograph of it. However, that specific patch of oils was small and messy, giving me very little to work with. At the time, I didn’t have a lens that could zoom in as far as I wanted, so I was unable to make a photograph that I felt did the subject justice.

Over the next couple of years, I found many other puddles with these oils, but they didn’t translate into “significant photographs.” I knew this subject matter had more potential. It wasn’t until 2018 that I came upon a patch of oils that was large enough to work with and as remarkable as the phenomenon could be. This is the first image I released of this subject matter, three years in the making.

It also took me years to release my first-ever image of mud cracks, despite making many attempts at photographing them wherever I found them. I’ll admit that back then, I was on a sort of treasure hunt, motivated by the incredible scenes other photographers had made of mud cracks — which isn’t how I approach photography today. But it wasn’t until after I made dozens of photographs of this particular subject matter that I finally felt I had something unique and satisfying to share.

Don’t let the excitement of finding a certain subject cloud your judgment about the actual photograph you have made of it.

Self Evaluation

Over the last five years, I have worked with nearly a hundred different photographers, suggesting ways that they can improve their images. When a photographer reaches out to me for feedback — whether it be for a portfolio review, in a critique group, or for only a single photograph — rather than just telling them what I think, imposing my judgment or personal taste on their art, I prefer to use The Socratic Method.

If I notice something that feels off or that I would handle differently, I will ask about it to see if it was something done intentionally or was maybe just an oversight. By merely pointing certain things out, I get the photographer to think more about their image, which usually results in their recognizing ways that they should change it all on their own. This also helps them to be able to see these things themselves going forward.

While it is very valuable to receive critique from other photographers — especially ones that you trust and feel are more experienced than yourself — the most important thing you can learn is how to critique your work. When it comes to your artwork, your opinion is the most important. The more you can take into consideration about your photographs, the better you will be able to determine whether they have been successful or not. This inevitably takes time. With more experience and a well-trained eye, you will be able to notice more distractions or flaws in your images and consider how well you have expressed what you wanted to.

Technical Flaws

While it is by no means the most significant part of what makes an image great or not, it is important to consider any technical flaws that may be present. I see these flaws sort of like the grammar or punctuation of your message. Of course, whether something is off also depends on your personal vision.

There are no universal criteria for whether an image is technically sound, since not every photograph needs to be tack sharp. A great image could be completely out of focus or blurry. The main thing is determining if there are any distractions in your photograph: anything that wasn’t included intentionally; things that pull the eye away from the subject or out of the frame, possibly by being too bright or too messy; visual tangents that may confuse viewers or cause their thoughts to wander too much in another direction.

Technical flaws can happen during every stage of making a photograph, and only some of those that occur in the field can be ‘fixed’ or mitigated through processing. While editing your image, it’s important to study it carefully to recognize any distractions that may still be present. Many distracting objects can be removed by darkening them, adjusting their color, or reducing their contrast within the surrounding landscape, and without damaging any of the pixels in the file. Other objects can be removed entirely using the clone stamp, spot healing, content-aware, or warp tools if necessary, but not without sacrificing some of the image’s quality. I always try to eliminate any remaining distractions through non-destructive methods first. What Does it Mean?

Many of our photographs, if not all, represent our meaningful experiences while in nature. Something we saw spoke to us on such a level that we made the effort to set up our equipment and capture it in a photograph. Photographs have the power to bring us right back to a moment, conjuring up the feelings and thoughts that we had, allowing us to experience it all over again. This usually happens for us regardless of how we may have captured the moment, since as the creators of our photographs we have additional context not available to someone who was not present at the time.

Even if my image is technically flawless, what makes a photograph “significant” to me is that it conveys the experience I wanted to capture. To determine this, I need to view my image as objectively as possible, detaching myself from it so that I may see it as an outsider, my judgment unclouded by bias. Ask yourself, “Does it express what I wanted to say?” If not, then maybe you need to hold off and try again sometime down the road when the opportunity presents itself.

Standing the Test of Time

One of the best ways to know how you feel about a photograph is by letting it rest for some time. I have found that after sitting for a few months, images can either marinate or fester. I’ve thought many photographs were great while I was making them in the field, but when reviewing them on my monitor several months later I felt they didn’t even deserve to be worked on. How many times have you been excited about an image that you published immediately, only to find that it no longer satisfied you a few days later?

No matter how good I may feel about an image once I have made it, I always let it sit for a while before coming back to it with fresh eyes and less emotion. Once the initial excitement of making an image wears off, we are in a much better space to determine whether we achieved what we wanted. Sometimes I’ll notice ways it can be improved through minor tweaks and adjustments; other times it just needs to be thrown out entirely. Or, with time, an image I was not very excited about will grow on me. It’s wise to wait a little before making a final evaluation.

Our memory fades as time passes, and it is much easier to look at our work objectively. Certain photographs will always impact you, possibly for the rest of your life, and others may no longer evoke a response after a couple of years.

Continual Curation

Apart from choosing what to release and what to throw out, curation should be an ongoing process throughout an artist’s life. Just because an image has been added to a body of work doesn’t mean it must stay there permanently. I feel that it’s important to constantly review your portfolio and remove images that no longer meet your standards or the overall quality of your work. Being aware of this can make selecting which images to publish a bit less stressful, since you can always get rid of them later if needed.

Adding new images to a portfolio is undeniably important, but what I feel elevates the overall quality of one’s entire body of work is trimming off the fat. Images that aren’t as evocative, impactful, or technically sound as your better work will only bring your portfolio down to their level. If your portfolio is too vast, with too many images to wade through, this can cause visual fatigue and make the viewer rush through or skip around, not giving the best images as much attention and energy as they deserve.

Something else I pay attention to while reviewing my body of work is if any of my images feel redundant. Even images made on opposite sides of the world can still feel like the same photograph and dilute each other’s impact by being too similar. I will then get rid of whichever one is inferior.

When considering whether to cull a certain image from my portfolio, I have found that it becomes much more straightforward if I ask myself, “Would I be happy if someone ordered a print of this image tomorrow? Would I want to hang it on my wall? Would I want to share this photo on social media today? If this were someone else’s image, would I still think it’s great?” If the answer to any of these is no, then it probably means I am not very proud of the actual image anymore, no matter what fond memories it is tied to. It may be time to let go.

It is also much easier to be objective toward your work if you are in a bad mood. When I am not very pleased with my photography, I will take advantage by going through my portfolio and removing images. At these times I find I am much more critical and less forgiving of myself and, in a way, more honest. If I regret deleting something later, I can always put it back. But to this day I have never reintroduced an image I had gotten rid of.

If you don’t miss it once it’s gone, there’s a reason for that.

Curation is a powerful tool for artists. It empowers you to establish your own standards and gauge the overall quality of your portfolio. Knowing you don’t have to release some preconceived quantity of work, you are free to take risks in making photographs. You can hold back the experiments that don’t quite meet your standard of perfection, and ensure your portfolio will always reflect your highest ideals. By selectively sharing your work, you give yourself space to explore new ideas and nurture a continuous learning process. Embracing this approach prevents stagnation and allows your artistic vision to grow and expand.

This is why it is so important not to get caught up in feeding the beast of social media. Some photographers may release a new image daily, others once or twice weekly. No quota is right for everyone, and you must develop your own based on your lifestyle, approach, and personal standards for your art. I don’t set any kind of quota for myself — I just let the images come naturally. I don’t expect myself to always be just as prolific. In some years I may release more work than in others, but I never relax my standards to increase quantity.

I am often asked, “What are your favorite images in your portfolio?” To which I always respond, “All of them.”

Every image in my current portfolio is there for a reason: It means something to me, and I have already deemed it “significant” after careful and honest consideration. I only release images that are special to me. Once they no longer feel special, I remove them from my portfolio, regardless of what kind of response they may have received from others. This is crucial to making a portfolio you can be proud of, one that will satisfy you for many years.

This article first appeared in Nature Vision Magazine. Nature Vision Magazine is a captivating publication that fuels your passion for nature photography. With thought-provoking articles, diverse perspectives, and stunning visuals, it explores the enchanting world of abstracts, wildlife, landscapes, and more. Delivered as a downloadable PDF, it offers flexibility and convenience for immersive exploration. Let Nature Vision Magazine be your guide as you embark on a journey of inspiration, growth, and creative expression in the realm of nature photography.

Subscribe to Nature Vision Magazine or purchase a single issue here.

About the author: Eric Bennett is a photographer based in Utah who has skillfully captured the breathtaking beauty of nature across over 30 countries. The opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author. Bennett is deeply passionate about using landscape photography as a means to inspire conservation efforts. Eric’s distinctive style is characterized by his ability to capture unseen perspectives and employ advanced processing techniques, resulting in visually striking images. You can find more of his work on his website.