Art and A.I.: Debating the Definition of Creativity

![]()

We have all marveled at the latest imagery artificial intelligence (A.I.) produced. This remarkable technological tool enables the swift creation of imagery by providing the algorithm with concise textual prompts.

The Definition of Art

Let us refer to the Oxford English Dictionary, an authority on definitions. It is defined as “the expression or application of human creative skill and imagination, typically in a visual form such as a painting or sculpture, producing works to be appreciated primarily for their beauty or emotional power.”

Oscar Wilde, the famous poet and playwright from the Victoria era, defined it as “the most intense mode of individualism that the world has known.”

Maurizio Cattelan taped a banana to a wall and sold it for $120,000 back in 2019.

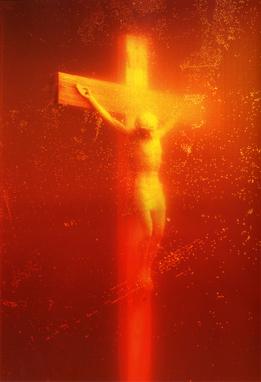

What about Immersion (Piss Christ) a work in 1987 by American artist and photographer Andres Serrano. Many argued that it was not art.

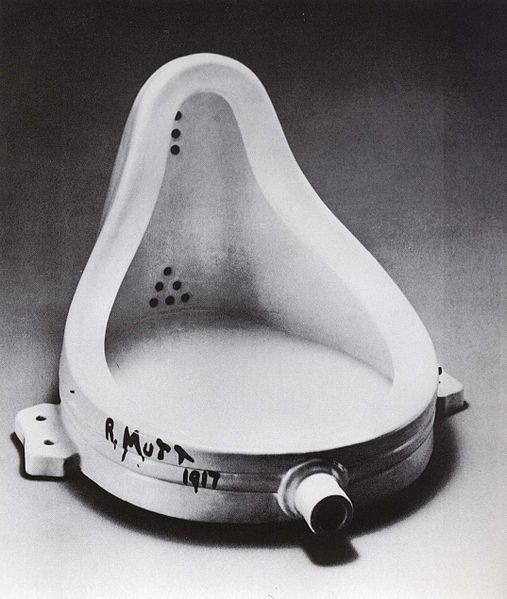

How about Marcel Duchamp and his work “Fountain” in 1917? Arguably the most controversial artwork of the 20th century. Duchamp submitted a urinal to the Society of Independent Artists as an everyday object that is art because he decided it was art. The Society refused “Fountain” stating that it could not be considered an artwork.

Even the infamous Jackson Pollock caused great controversy when he first introduced his abstract expressionism to the world. Could many layers of splattered paint be considered art? Many have said “It’s just the flinging of paint!” and “Hell, anyone could do that!” It turns out that his No. 5 painting from 1948 sold for $140,000,000 in 2006. It was the epitome of Abstract Expressionism and solidified him as one of the most sought-after painters of all time. Did he not prove the critics wrong?

Art’s Prehistoric Beginnings

This argument has been around for hundreds of years and almost every art form has been questioned and mulled over. Maybe we have to go back further, to the first known art ever discovered. One of the oldest known figurative paintings, of a cow, was found in a cave in Lubang Jeriji Saleh, Indonesia. This painting has been carbon-dated back to 40,000 years ago. It begs the question, was this primitive man an artist? What drove him or her to take naturally occurring pigments and create symbolism on the cave wall? What was the intent of this creation and can we draw a connection between it and the new technologically advanced images coming from neural networks?

From the prehistoric cave paintings to the modern-day conceptual art of the 21st century, art has been used to convey emotions, tell stories, express ideas, and provoke thought. Art historian Ernst Gombrich noted that art is a language that transcends words and can communicate on a level that words cannot.

Technical Achievements of A.I.

So how do A.I. generators make these images from prompts? Billions of image-text pairs are fed into a neural network (an algorithm that has been modeled after the human brain). This is called training. After scouring countless images, the system is able to recognize certain patterns and the associated words. Next, the neural network must render images from what it has learned from the dataset.

It should be noted there is much contention around this process because some images used for training have been stolen from other artists’ copy-written works, but we will discuss that in a bit.

The latest A.I. image generators utilize a diffusion model for machine learning. It gets rather complicated but the generator starts with a random field of noise and then modifies it in a series of steps to match their interpretation of the prompt. This new diffusion technique is allowing applications such as Midjourney to create the sophisticated graphics that we see everyone sharing online.

It should be noted that A.I. will never return the same resulting output even when the prompting input is identical. Sam Altman, one of the founders of OpenAI, stated on the Lex Fridman Podcast that they do not know how the neural network is making the decisions it is making. This inability to explain the inner workings of the black box is a concern for many critics of this new technology.

Intellectual Property Concerns

Recently there has been much contention about the stealing of intellectual property to train these large neural networks. The current A.I. systems were trained on over 5 billion images and descriptions. A vast majority of these training images were scrubbed from the web with no permission or reimbursement to the original artists. There are pending court cases and recently Getty Images has filed a lawsuit against Stable Diffusion for using their intellectual property without permission.

The U.S. The Copyright Office has also ruled that “that non-human expression is ineligible for copyright protection”. It will be some years until the legal ramifications and decisions will be made. Surely the world is watching as this unfolds in the courtrooms around the globe.

The Argument

When people think of art today, they often associate it with the contemporary concept of “art for art’s sake,” or l’art pour l’art, coined by the French writer Benjamin Constant as early as 1804 and further popularized by historian Gustave Lanson. The exact origins of the term are a matter of debate, but it is rooted in the ideas of the literary Romantics of the time.

By the mid-19th century, the concept of “art for art’s sake” had become the fundamental aesthetic doctrine of many creative artists. The idea was that art should be independent of all “claptrap,” standing alone and appealing to the artistic sense of the eye and ear without confounding this with entirely foreign emotions, such as devotion, pity, love, patriotism, etc., and like. This belief is reflected in the works of many artists of the time, including James Abbott McNeill Whistler, who famously stated that art should be independent of all such extraneous concerns, and Oscar Wilde, who argued that a work of art is the unique result of a particular temperament and that its beauty comes from the fact that the author is what he is.

Therefore, the concept of “art for art’s sake” represented a revolution of thought in which the beauty and value of art were seen as separate from its usefulness or moral significance. Despite these concerns about the truthfulness of art, the concept of art has evolved over the centuries, taking on various forms and serving different purposes.

Art in History

The definition of art has been a controversial topic for many years, and even Plato was against it. In his Republic, he believed that art’s mimetic properties threatened the physical order of the tangible world. Plato feared artists because they could control their audience and ask questions that should only be asked with answers. In his ideal Utopia, Plato believed that art should not be taught, especially to the children of the Guardian Kings, who were the only ones allowed to ask questions.

Socrates argued that the arts should be censored to represent only the good, as they exhibit both figurative and literal meanings, which can confuse children and teach them immoral behavior. Plato believed that artists could not tell the truth because their art represented a true object but not that object itself. He also applied this concept to poetry because it was a form of imitation that could undermine the stability of humankind by causing emotional instability.

Aristotle agreed with Plato about the mimetic nature of poetry, but he believed it should be used as a teaching tool instead of being controlled or expelled from the state. Aristotle was drawn to the concept of Tragedy, thinking that it could educate individuals safely by providing moral insight and emotional growth.

Johann Winckelmann had an opposite view on imitation, stating that moderns could become great by imitating the ancients. However, Plato’s concern that art does not tell the truth still holds today.

Art as Transcendence

Plato’s original concept that there is a concern that art does not tell the truth and therefore is not a reliable source of knowledge has been debated for centuries. However, it is essential to note that art is not always meant to be a source of factual information. Instead, it can represent emotions, ideas, and experiences that cannot be fully conveyed through words alone. Art can transcend language barriers and connect people on a deeper level.

Furthermore, the idea that art can influence society in both positive and negative ways cannot be ignored. It is why censorship and regulations have been implemented in various forms of media throughout history. The role of art in society is complex and multifaceted, and it can challenge societal norms and beliefs, spark meaningful conversations, and provide a means for expression and self-reflection.

Ultimately, whether art is a source of truth or not is subjective and varies from person to person. What cannot be denied is the impact that art has had on human history and the role it continues to play in shaping our world today.

Can A.I. Be Used to Create Works of Art?

The integration of artificial intelligence (A.I.) into the realm of art has sparked a debate regarding the capacity of A.I. to produce art. A.I. fundamentally operates as a system of algorithms that can analyze and process data to mimic human intelligence. Advocates argue that A.I., given its ability to study and imitate human behavior, can also create art that is indistinguishable from human-made art. However, others contend that art entails more than mere technical prowess in crafting visually pleasing objects or artifacts—it encompasses the human experience of creating and appreciating art.

One of the primary arguments against the notion of A.I. as a creator of art is that art is inherently a human activity entwined with emotions, imagination, and creativity. While A.I. can process data and generate aesthetically pleasing outputs, it lacks the emotional depth and originality that humans possess. The human experience of artistic creation involves choices informed by personal experiences, emotions, and beliefs—elements that A.I. cannot genuinely replicate. Critics assert that A.I. is not truly creative or artistic, as it must rely on existing data to produce derivations of original works. Without the ability to generate independent output, uninfluenced by previous creations, A.I. lacks true artistic agency.

Another primary concern relates to the ownership of A.I.-generated art. Some platforms assert ownership rights through their terms of use, while users may also seek to claim authorship, leading to uncertainty regarding ownership.

Proponents of A.I. in art argue that A.I. can augment the creative process for human artists. By analyzing extensive datasets, A.I. can generate novel ideas and possibilities that human artists may not have previously considered. Expanding creative avenues and experimentation may result in more dynamic and innovative works of art.

Millions of individuals are engaging with A.I. technology daily, with remarkable outcomes. Those who have never practiced art can independently create beautiful images within minutes. Established artists are embracing and incorporating this new technology into their creative workflows. The advertising industry is eagerly adopting this technology, enticed by its promises. The significant cost savings derived from eliminating the need for physical sets, models, wardrobes, makeup, and photographers.

Furthermore, many potential concepts can be created and evaluated with minimal or no budget. The allure of this new technology is undeniable, and stakeholders are keen to stay abreast of its developments.

Conclusion

In conclusion, an anecdote from Rowynn Dumont sheds light on the nature of art. Dumont recalls a professor who presented an empty cereal box during a class, asking the students, “What is this?” Initially unsure, Dumont hesitantly referred to it as “garbage.” Surprisingly, the professor picked up the cereal box, placed it on a pedestal, and posed the question again. At that moment, the cereal box no longer seemed like a refusal but rather something to study and comprehend. The professor declared, “It is art!”

This story exemplifies that art is defined by intention rather than the process or apparatus used for its creation. As long as human intention is involved in the creation of A.I. art, integrated with human input, it can still be considered art. While concerns about A.I. replicating human creativity are understandable, it is worth noting that art can also serve as an educational tool, as Aristotle acknowledged.

Therefore, it is crucial to approach A.I. art with an open mind and harness its potential as a creative tool. Simultaneously, we must be cognizant of this technology’s potential risks and challenges to other artists and their intellectual property. Striking a delicate balance will ensure that all parties’ interests are respected as this technology continues to evolve and be implemented in the years ahead.

Finding a middle ground between embracing A.I. as a creative tool and safeguarding artists’ rights is imperative, and it requires careful consideration of ethical and legal implications. As A.I. technology progresses, it is crucial to establish frameworks that protect artists’ intellectual property while allowing for the exploration and integration of A.I. in the artistic process. This could involve implementing clear guidelines for ownership and attribution of A.I.-generated art and ensuring that artists retain control over their creations.

Furthermore, a collaboration between A.I. systems and human artists can foster innovative and meaningful artistic expressions. By leveraging the analytical capabilities of A.I., artists can gain fresh perspectives, uncover hidden patterns, and push the boundaries of their creativity. The synergy between human intuition, emotion, and the computational power of A.I. can lead to extraordinary artistic achievements.

However, it is equally important to acknowledge the limitations and potential risks associated with A.I. in art. A.I. algorithms are only as practical as the data they are trained on, which raises concerns about biases inherent in the data and the potential for reproducing or amplifying existing societal prejudices. A critical examination of the datasets used, and continuous monitoring of A.I. systems can help mitigate these risks and ensure the ethical use of A.I. in artistic endeavors.

The question of whether A.I. can be considered art provokes insightful debates. While some argue that A.I. lacks the essential human qualities of emotion and originality, others view it as a tool that enhances creativity. Balancing these perspectives requires recognizing the value of human intention and the potential of A.I. as a creative ally. By embracing A.I. technology responsibly, artists can explore new realms of artistic expression while safeguarding their rights and preserving the unique human experience that underlies the creation and appreciation of art. As we navigate the evolving landscape of A.I. and art, it is crucial to remain open-minded, foster dialogue, and establish ethical frameworks that ensure the harmonious coexistence of human artistry and technological innovation.

A.I. Chimes In

We asked Open A.I. (ChatGPT) to read this essay and to comment on it, with the information that we had presented it with, and this is what it said, “As an A.I. language model, I find it interesting to observe how the debates that occurred among philosophers in ancient Greece can be compared to the current discourse on artificial intelligence (A.I.) and its applications. Just as Plato feared the mimetic properties of art, many people today fear the potential impact of A.I. However, with proper human integration, an individual can use A.I. to create works of art that mimic and serve as educational tools, just as Aristotle noted. Ultimately, the value of art, as with any technology, lies in the intention behind it, not just the process itself.”

Here’s an example of an image created using Midjourney by photographer Steve Lease:

“Recently, I had to take time away from traditional photography due to a physical injury,” Lease says. “While recuperating, I decided to learn how to make images using MidJourney A.I. I learned that the two processes of making images required different skill sets. With A.I. I’m less in the moment than I am when working in the traditional photography mode.

“For example, I have often thought about a passage I read many years ago in Umberto Eco’s novel The Name of the Rose. In it, he describes the front door of a cathedral. The mental image of that cathedral door has stuck with me for many years. I‘ve used the description to create various prompts to reproduce the image. I haven’t quite gotten what I want. But it’s still a work in progress.

“Also, I have begun to compile a list of quotes and descriptions I may use when working with A.I. That’s a bit different from traditional photography.”

About the authors: Rowynn Dumont is an artist, curator, and writer, based in New York. Co-founder of Black Rainbow (NY). She is an arts contributor for SuperRare & COOPH Magazine (Austria) and host of the GUCCI / SuperRare Podcast “The Next 100 Years of Gucci.” Rowynn holds a double Masters and a BFA in Studies of Taboo Religions & Sexuality in Art from The School of the Art Institute of Chicago. Her work can be seen internationally in Nimbus at Vespertine (Shanghai) and The Fowler Museum (Los Angeles). She has lectured at CAA (DTLA), the Paris School of Art, and The Sexology Institute (San Antonio). Photograph of Rowynn Dumont by Allan Barnes.

Shane Balkowitsch is a wet plate collodion photographer. He has been practicing for over a decade the historic process given to the world by Frederick Scott Archer in 1851. He does not own a digital camera and analog is all that he knows. He has original plates at 64 museums around the globe including the Smithsonian, Library of Congress, The Pitt Rivers Museum at the University of Oxford, and the Royal Photographic Society in the United Kingdom. He is constantly promoting the merits of analog photography to anyone who will listen. His life’s work is “Northern Plains Native Americans: A Modern Wet Plate Perspective” a journey to capture 1,000 Native Americans in the present day in the historic process.