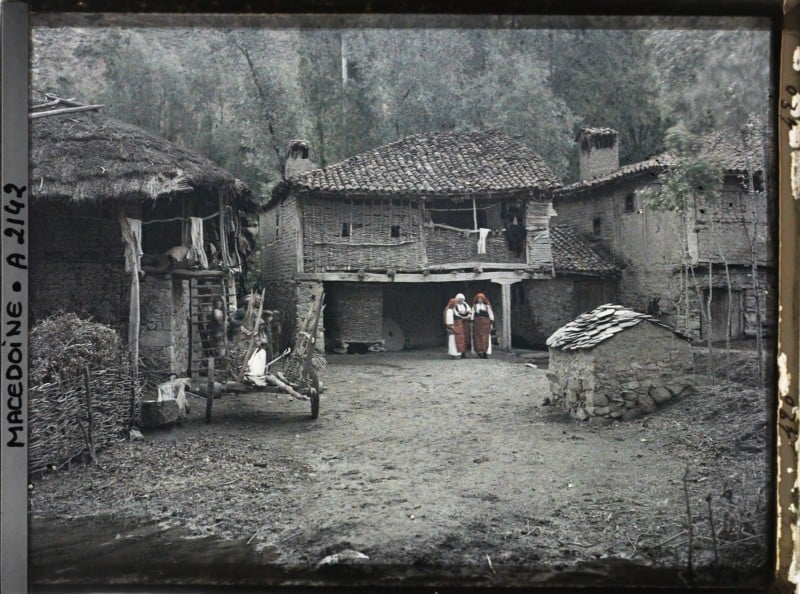

Museum Releases Early Color Photos of a Vanished World a Century Ago

![]()

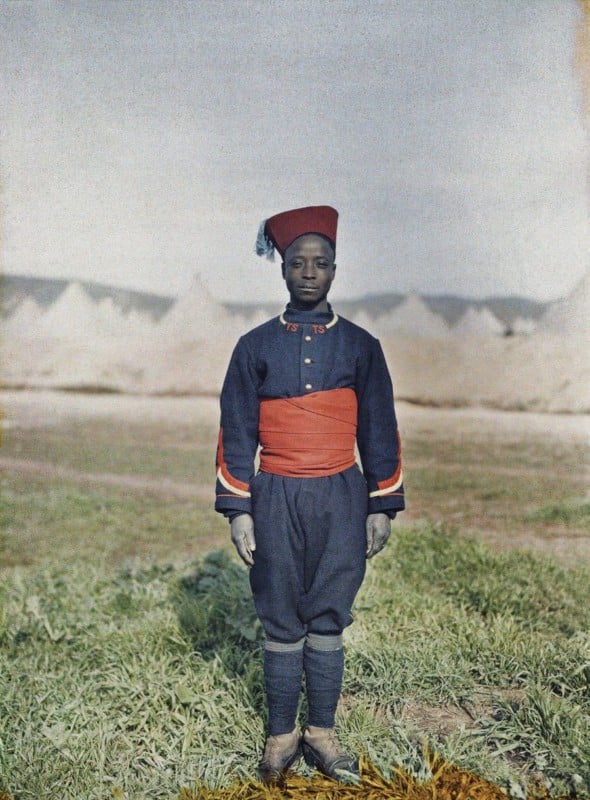

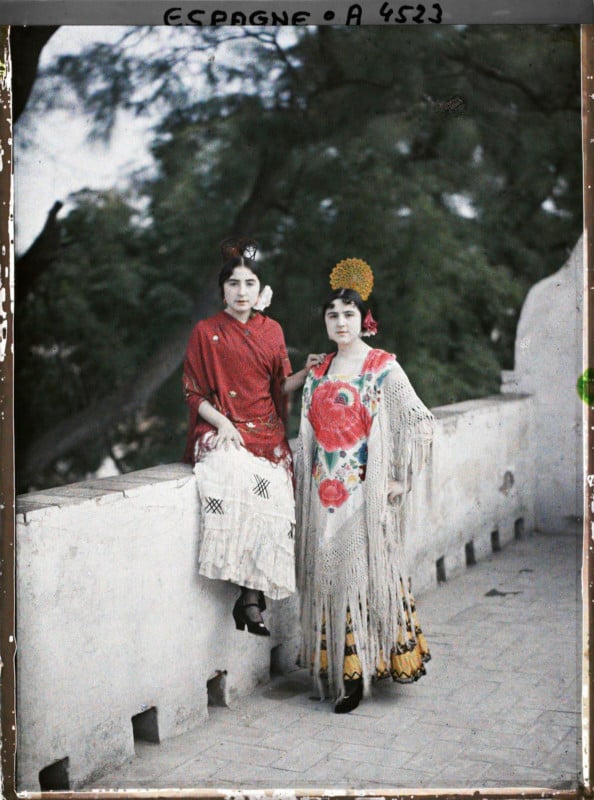

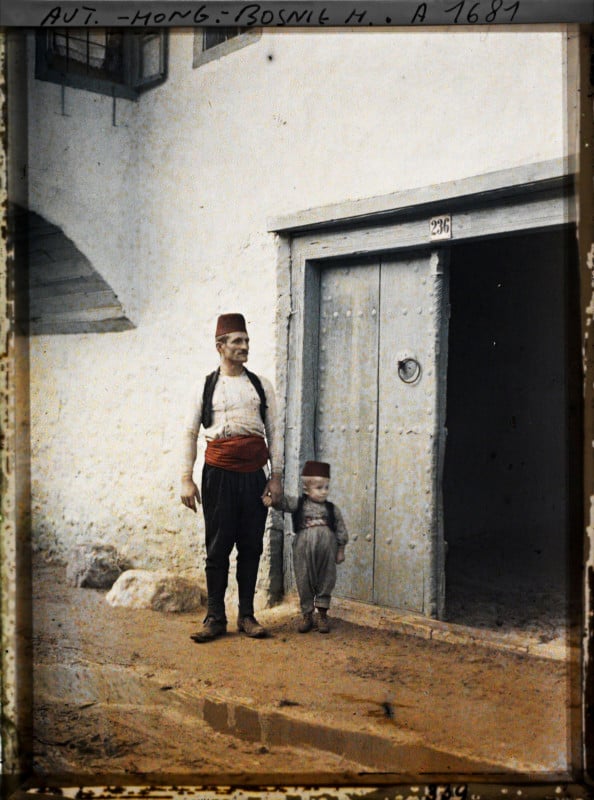

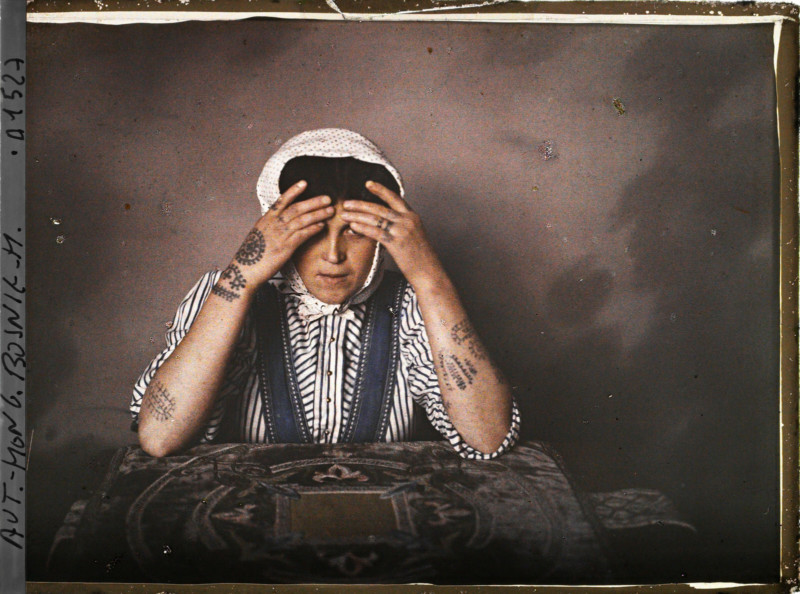

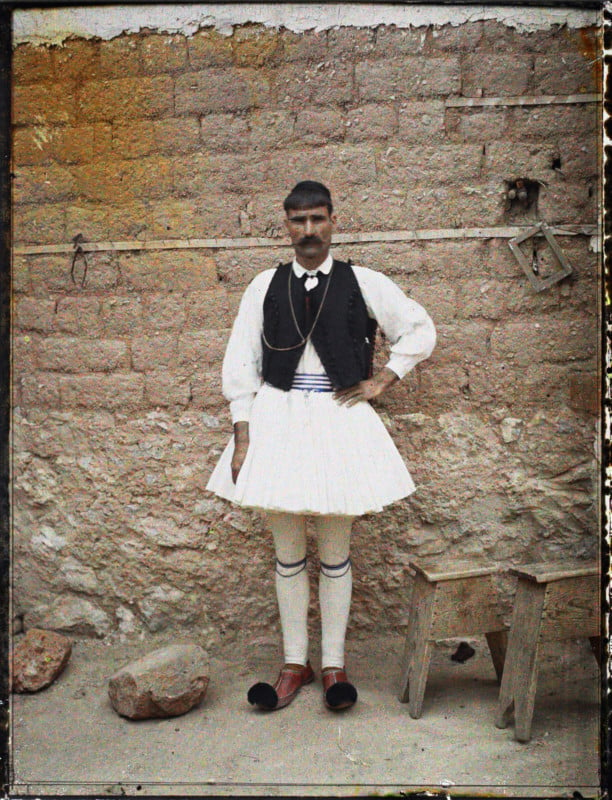

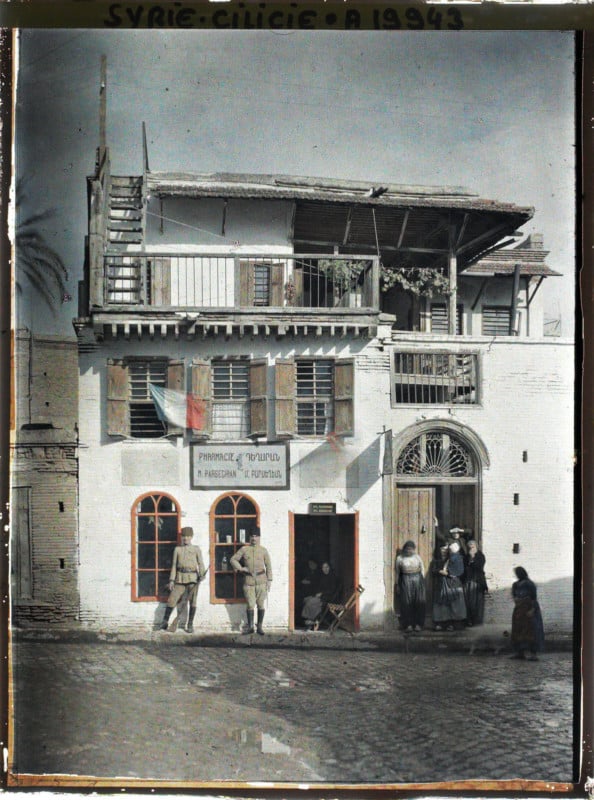

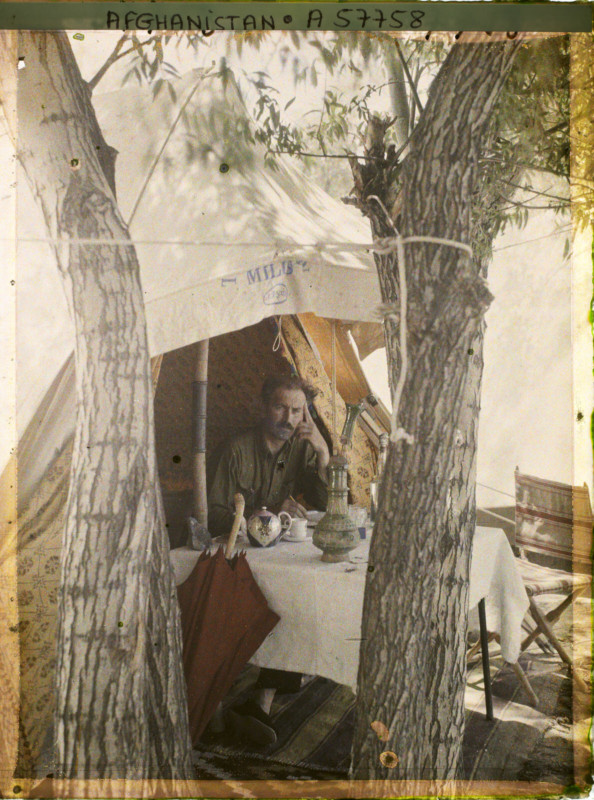

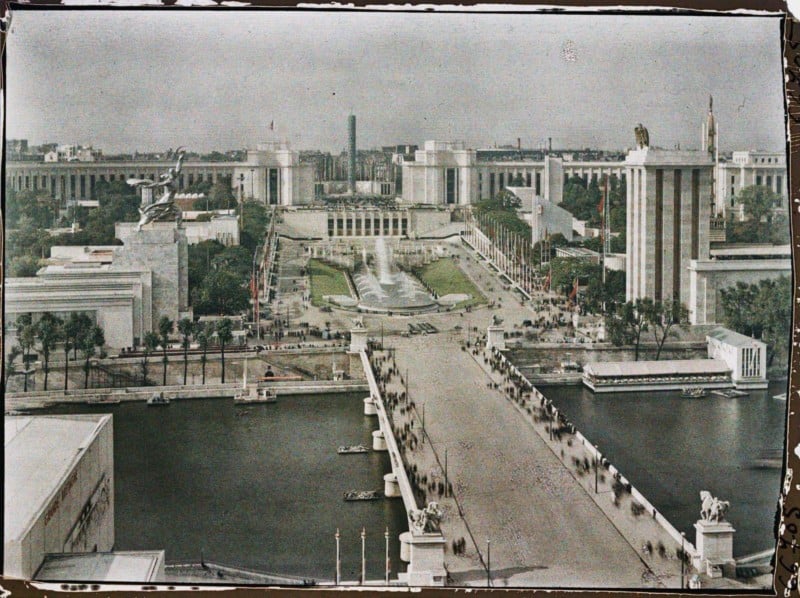

Stunning color images recently made available in high resolution by a French museum capture much of the world as it was transformed by technology and geopolitics 100 years ago.

This image of a young Serbian man butchering a sheep in 1913 in Krusevac, in central Serbia, is one of tens of thousands of historic color photos recently made available in high resolution by France’s Albert Kahn Museum.

The museum, in the west of Paris, reopened in April after a years-long architectural renovation during which they also transformed their digital portal.

Some 72,000 high-resolution photos from a project called the Archives of the Planet have been made available for download by the museum.

The images had been possible to view previously but only in low quality through a difficult-to-navigate website.

The Archives of the Planet project was launched in 1909 by French banker Albert Kahn soon after autochrome, the first viable color film technology, became commercially available.

Kahn was a French banking titan who funneled much of his fortune into philanthropic projects.

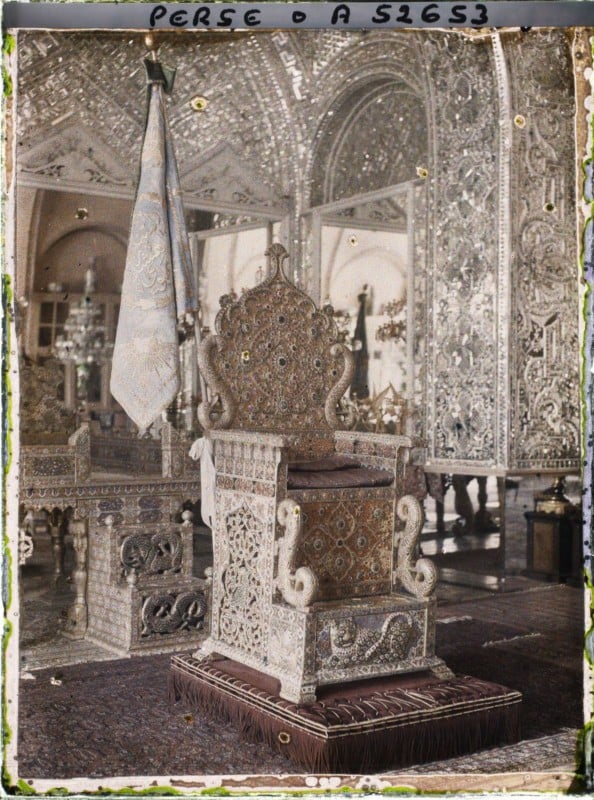

With his massively ambitious photography project, Kahn sought to document the world as it was being transformed by globalization.

In some cases, Kahn’s photographers were making the first-ever color photos of the countries they were working in.

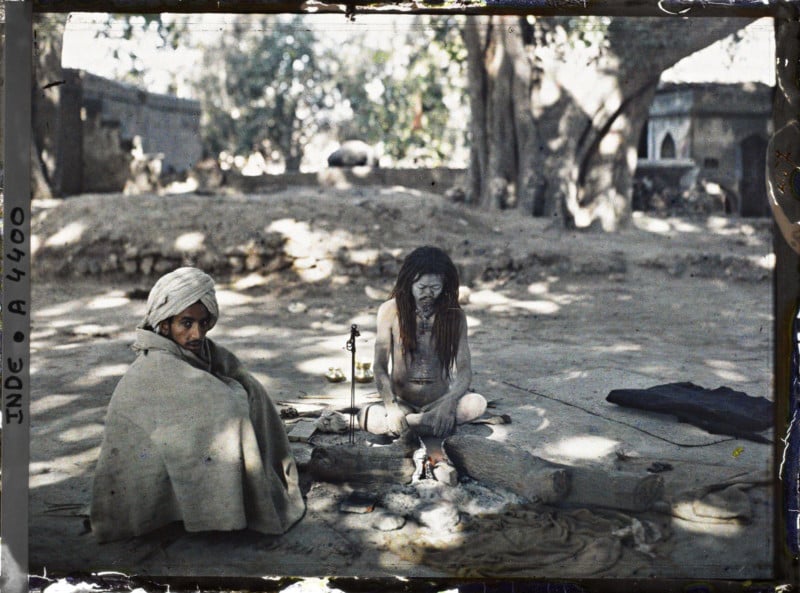

Jean Brunhes, who was Kahn’s director for the project, summarized the Archives of the Planet as “using the instruments which have just been born, to capture and preserve the facts of the planet that are about to die.”

A dozen of France’s best photographers were tasked by Kahn to travel the world in order to “preserve once and for all certain aspects, practices, and modes of human activity whose fatal disappearance is only a matter of time,” the banker explained.

A spokesperson for the Albert Kahn Museum says the revamped online archive will “allow the discovery of a wide selection of works.”

The museum spokesperson added that the “reuse of images will be widely encouraged thanks to the online availability of a large part of the collections under a Creative Commons license.”

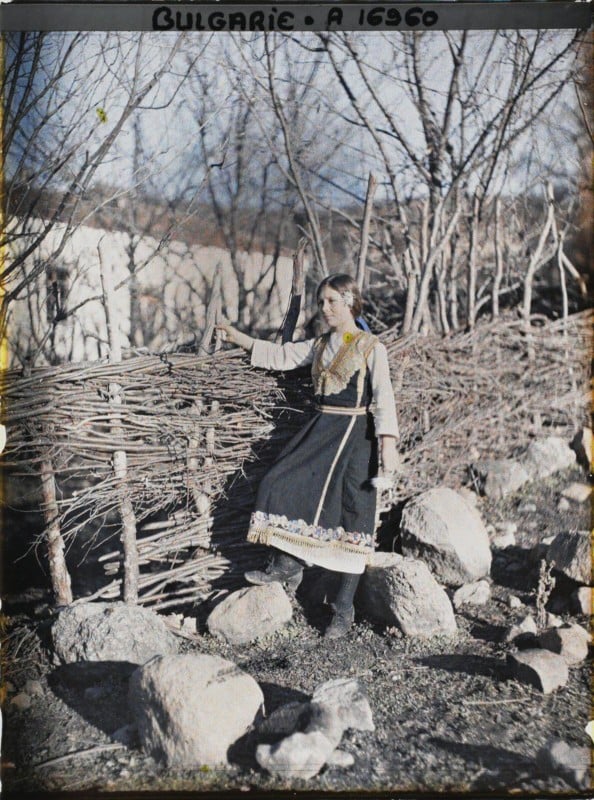

The autochrome color film technology used by Kahn’s photographers was first introduced in France in 1907 and immediately caused a sensation.

One commentator noted in 1908 that the autochrome technique replicated “the colors of nature in a most startlingly truthful way.”

Autochrome film used millions of “pixels” of dyed grains of potato starch pressed into emulsion to create color photos.

The pastel-shaded, slightly speckled images that autochrome produced were described as being “the color of dreams.”

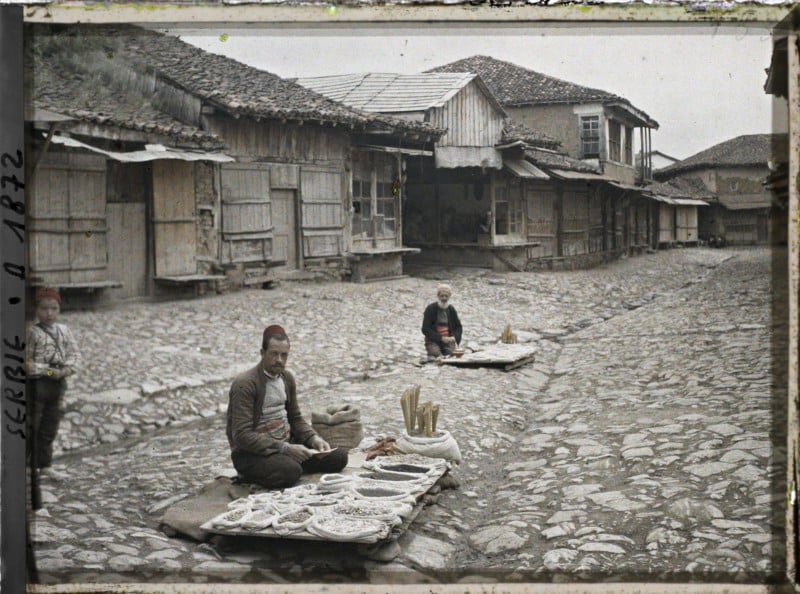

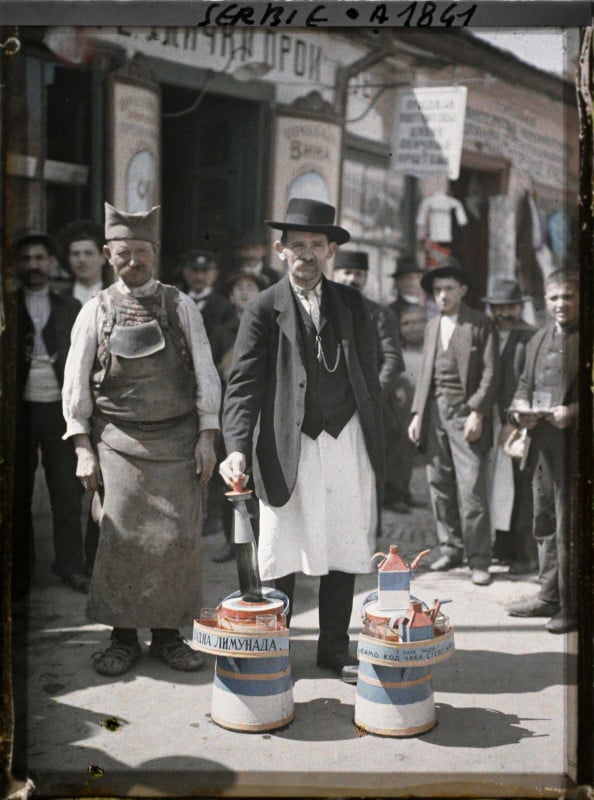

The original caption on the photo above notes that the two lemonade containers were painted in the vivid blue, red, and white of the Serbian flag, which indicates the colors of the autochrome photographs are significantly muted when compared with reality.

Autochrome photographic plates were easy to use but expensive to buy and difficult to exhibit.

The main disadvantage of the autochrome technology, users said, was its low sensitivity to light, which necessitated long exposures.

Exposure times for autochrome photos even on bright days stretched into seconds, meaning bustling street scenes were impossible to capture adequately and portraits needed to be strictly posed.

In total, the photographers commissioned by Kahn traveled to more than 50 countries and captured not only the color photos but around 100 hours of black-and-white film footage as well.

Film footage was used by Kahn’s photographers to capture the candid daily life that the color photographs were unable to freeze into a clear photo.

Kahn was forced to end the photographic project soon after the Great Depression shattered the world’s financial markets.

Kahn went bankrupt in 1932. He died in 1940, soon after Nazi forces occupied France.

The visual record he and his photographers left behind have been called some of the most important color images ever made.

About the author: Amos Chapple is a Kiwi who photographs and writes for Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. He has been published in most major news titles around the world. You can find more of his work on his website. This article was also published on RFE/RL.

Image credits: All photographs courtesy Musée Albert-Kahn.