Why Adding ‘Film Grain’ to Digital Photos is Trickier Than You May Think

![]()

For months now I’ve been obsessed with emulating the film look with my digital photos. It all started with me exploring the panoramic aspect ratio of 65×24 and other wide aspect ratios, trying to understand what makes a photo cinematic.

Film Grain and Digital Megapixels

In order to recreate grain well in our digital photos, we first have to understand what grain is. When it comes to photographic film, images are composed of grain. Be it silver halides or dye granules, they are organic shapes that are distributed unevenly in an emulsion and when exposed to light they create the image you finally see.

Now let’s try an understand what this means for digital photographers.

The fact that images are composed of grain means that the grain should be the smallest detail in the image. So all those megapixels you paid a lot of money for are kind of working against you right now. The higher the ISO of the film you want to emulate, the bigger the crystals would be. Big crystals mean a lower level of detail.

So, when reverse engineering this for digital, you will have to either lower the resolution or the sharpness of your images. The easy route is a gaussian blur on the entire photo, but if your goal is film emulation, you are already looking into mist/haze filters and other ways to do this in camera.

Regardless of the method, you pick for lowering the sharpness, you are aiming to have small details of the image (like hair) as thin as the grain particles. Basically to goal is to have the pixels match the size of the grain.

![]()

The Biggest Difference Between Grain and Noise

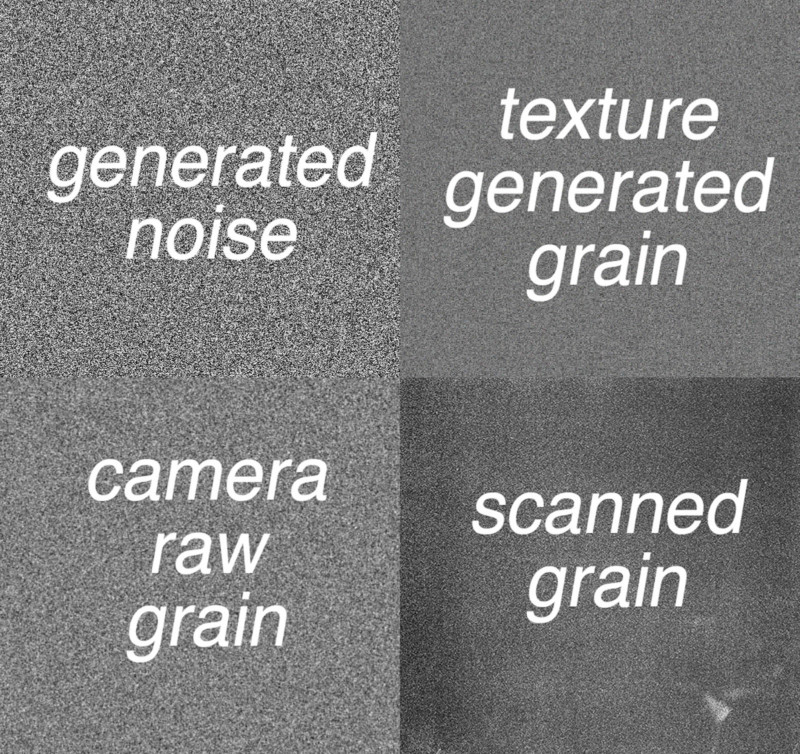

Another very important is the fact that the film grain is made out of organic particles. That means not all the grain particles have the same size and they are unevenly in the emulsion. This is the most significant distinction between grain and noise.

Noise, by nature, is digital so it is all square-shaped, like a pixel, and it’s uniform in nature because pixels are just a grid of little, tiny squares. So when you look very closely you can easily tell that noise and grain are two very different things with grain achieving actual randomness of size and positioning while noise is just a table of black, white, and grey squares.

This is why you should never use a noise overlay layer on top of a photo in order to emulate grain.

One more aspect that we should keep in mind is that the color film grain is made of dye particles as well. So just overlaying black and white grain on top of a digital photo will not be enough for a good grain emulation. Also if you are adding the grain after your color grading, you should make sure your grain has a similar color treatment to your shots.

Grain in Shadows and Highlights

A final note deriving from the fact that a film image is composed of particles: due to the way we perceive images, there seems to be a lot less grain in highlights and deep shadows but since particles are what the image is composed of, there can never be no grain at all in any part of the image.

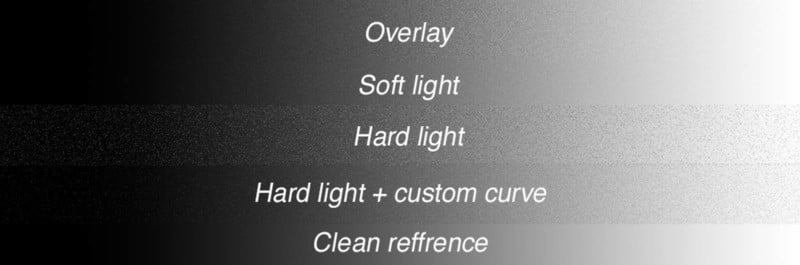

This matters because if you just take a grey overlay and blend it with Soft Light or Overlay blending mode on top of your photo, you will end up with perfectly clean areas near the ends of the spectrum.

Below you can see how a scanned grain overlay looks on a black-to-white gradient with different blend modes. For me, Hard Light blending mode seems to be the closest one for shadows and highlights, but at the same time it’s a bit too harsh for my taste in the mid-tones so further tweaking will be needed.

There’s No One-Size-Fits-All Solution

Now to be perfectly honest, going into this I was expecting the answer to be something like don’t add noise, and if you want to generate some grain, make sure you have multiple layers so not all particles will be the same size. Or even better, use scanned grain from actual film stock. But reading more about this topic made me realize that in order to get a believable result it’s not enough to discuss what overlay is the best to slap on top of a photo after you finished editing everything else.

There are an infinite number of ways to add grain, and with the current resurgence of the film look, I’m sure many more will pop up as well. And at the moment some of the most believable results seem to come from phone apps or plugins, but this poses two problems for me and my workflow.

First of all, I hate sling-shotting files back and forth to my phones — that means saving stuff to jpeg again and again and the quality will drop (through probably not enough to be noticeable). And more importantly, I like my workflow to be non-destructive so I can just go in and adjust things on the fly a few days later, and this can only be achieved with layers in Photoshop at the moment.

![]()

After all the research I’ve done, I can’t give you a simple one-click solution to this problem if your goal is to have credible film emulation. But I DO have a list of pointers that will help you develop your own method and bake it into your own professional workflow.

- Use scanned overlays instead of generated noise.

- Lower the quality of your photo so you don’t have smaller details than the particles.

- Color grade after you added the grain.

- Have some grain shadows and highlights.

- Take a step back and look at your images as a whole, don’t just add grain to everything.

At the end of the day, I do think it depends on how you are going to display your work and how much time you have to invest into making your digital files look as close to analog as possible.

You can use the Lightroom sliders or a phone app and call it a day for a quick social media post because the compression will ruin the look anyway. But when going for a big art print or using the image for an ad campaign, quality matters and the devil is always in the details.

About the author: Vlad Moldovean is a photographer and visual artist from Brasov, Romania. The opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author. You can find more of his work on his website, Facebook, 500px, and Instagram. This article was also published here.