We Cry in Silence: A Photo Investigation of Human Trafficking

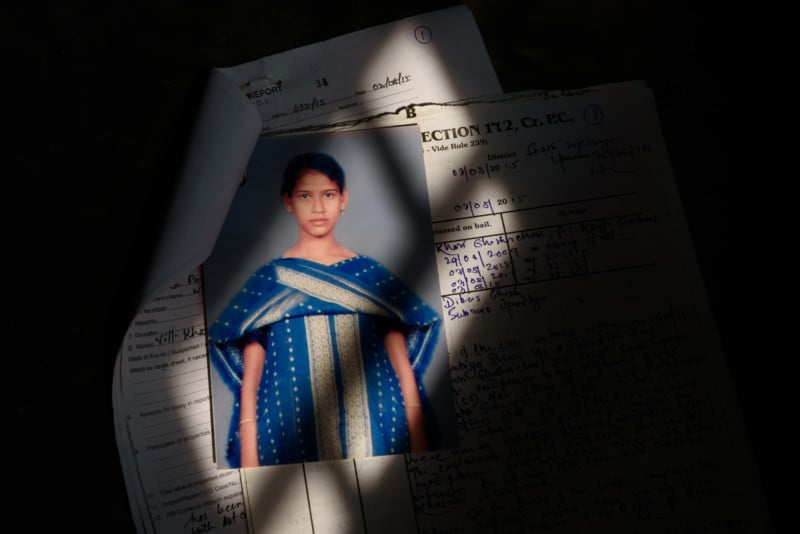

Award-winning photojournalist Smita Sharma has launched a photography book project that documents the vulnerability of young girls that are victims of human trafficking between Bangladesh, Nepal, and India.

A Widespread Issue That is Regularly Underreported

The painstaking issue of young lives affected by trafficking and sex crime is not a new topic for Sharma, based in Delhi, India. As a photojournalist, she has covered various human rights, gender, and social issues locally and globally. She has shot assignments for major publications, like National Geographic Magazine, documenting child marriage, sexual violence, the effect of pregnancy on girls’ education in Kenya, and others.

Her recent project is “We Cry in Silence,” a photo book that looks at the widespread issue of trafficking minors for sex in Bangladesh, Nepal, and India. Using her substantial experience covering critical issues on the ground, Sharma’s book “seeks to address this complex, global issue at the local level, and open a dialogue to move people to work towards a regional solution.”

Speaking to Photography Ethics Centre, Sharma noticed a lack of in-depth reporting on this issue, when she previously covered a story for National Geographic, titled “Stolen Lives: The harrowing story of two girls sold into sexual slavery.” In addition to publications skimming over the topic, she also found that between 20017 and 2016 trafficking increased by 140% in South Asia, East Asia, and the Pacific.

As part of the project, Sharma has photographed and interviewed more than 50 young survivors of sex and domestic trafficking. In addition, she has acquired access to traffickers, too, and interviewed them to understand the methods they use to psychologically manipulate and trap vulnerable girls.

The reasons for victims falling prey to trafficking criminals vary but all cases result in suffering. Some victims become trapped in domestic servitude through faux employment agencies, while others are manipulated by men professing love or trafficked by relatives who later lock them in a brothel and leave them unable to escape.

Trilingual Book About the Lives Disrupted by Trafficking

The photo book which contains Sharma’s photographs and the testimonies of victims and survivors has been translated in Bengali, Hindi, and English and serves as a means of creating permanent evidence of the dangers many young women face. The resulting photobook, published in association with the FotoEvidence Association, will be distributed to schools and libraries in India, as well as local law enforcement agencies.

at all hours. Sayeda was rescued and sent to a shelter in West Bengal, India. She was preparing to return

home to Bangladesh when she died from a liver problem caused by excessive drinking at the brothel.

The “We Cry in Silence” project will also see a release of an accompanying newspaper zine, traveling exhibits, and community events in collaboration with local partners, like Shakti Vahini, an Indian advocacy organization for human rights and democratic institutions, Sanlaap India, an anti-trafficking organization, and others.

Detailed Coverage Despite Risks to the Photographer

While conducting the research and working on her project, Sharma was pregnant, which meant taking additional safety precautions. In addition, she found that her choice to dedicate time to this meaningful project was challenged, too.

“My original doctor, a woman, was not supportive and asked me to cancel my work for National Geographic and advised me to start taking photos of flowers,” she tells PetaPixel. “I found that very classist and humiliating.”

![]()

“For the next six months I had to get an ultrasound every 15 days to ensure I wasn’t getting any infection as I was working in some unhygienic and dangerous places,” she adds. “It’s been a hard journey but very fulfilling and I am very grateful for the support of Fotoevidence and Sarah Leen who is editing this book.”

The project will be funded if it reaches its goal on Kickstarter by April 26, 2022. If successful, the book will be published in August in India and will be available globally starting in September.

Disclaimer: Make sure you do your own research into any crowdfunding project you’re considering backing. While we aim to only share legitimate and trustworthy campaigns, there’s always a real chance that you can lose your money when backing any crowdfunded project.

Image credits: Photos by Smita Sharma.