Why the Film Lab of the Future is Open Source

![]()

We are approaching the peak capacity for film photography labs. The machines are old, the parts are scarce, the demand is high. The measly Kodak Pakon Scanner, terrible it may be, fetches absurdly high prices.

We need to think long term, and the sooner the better, how will film processing work in 20 years? What about 50 years? The solution is inevitably open source, some sort consortium between photo labs and other interested parties on a commitment for free and libre IP on parts and technology for scanners/processors. “Free as in speech, not beer.” Because we know that the proprietary model will not work in this going forward as indicated in the death of Fuji machinery, tooling, and support.

Scanners

“DSLR scanning” is undoubtedly the answer. The problem is achieving scans at scale and in a short time frame. I’m sorry darkroom people, but the market wants high-quality scans because we live in a world where social media dictates the trends of photography. In the decade since the last Frontier scanner was made, sensor and optics technology has improved so much — imagine the capacity of using the 50MP Canon 5DSR sensor along with Sigma Art macro lenses.

We need to work towards a future where the limiting factor of film scans is solely the available mainstream photographic technology.

DSLR scanning as it currently stands is an arduous process. The workflow needs to be simplified, achieving high-quality scans in minutes with minimal post processing effort instead of hours via clunky Lightroom/Photoshop plugins. This involves creating an interface that has a live preview and enabling easy density and color balance adjustments. Along with this is a standardization of some form of an automatic carrier for this process (particularly for 35mm).

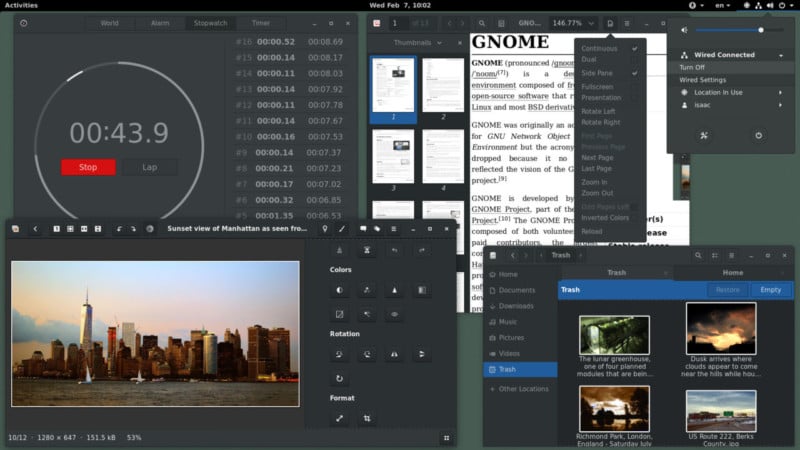

Software also becomes a crucial component of this problem. If you’ve seen an SP3000 in person, you know they run on Windows 2000 for the most part. This is due to the proprietary nature of how that software was written and the end of life for the development of that software. The only way of achieving the long term support we need is a commitment towards Linux as the primary platform, though if source code were available, it could easily be platform agnostic. Ideally, though, it should be developed for Debian/Ubuntu first and foremost as it the most ubiquitous Linux distribution.

We cannot risk the future of film photography on the whims of a sole corporate entity. Whether it be Fuji, Adobe, Noritsu, or Microsoft. Another reason to run Linux is the ease of deployment and distribution, enabling the possibility of preinstalled .iso images.

Processors

![]()

A minilab film processor, as I like to put it, is a bicycle and an aquarium mashed together. In the age of Arduino’s and Raspberry Pi, a film processor built from scratch is 100% achievable.

Several projects replicating a Jobo or autolab exist but what needs to be replicated are the leader card systems. They are so much more efficient and I’d argue should be the first pursuit of a supposed Open Film Lab project. We have the technology available to us to build these already. The possibilities are endless, we could bring back E6 processing at scale perhaps even Kodachrome processing (though this involves the release of the chemistry patents from Kodak).

The Business Opportunities

Working towards a modular and open platform will provide secondary revenue opportunities for film labs in building small systems and/parts providing the opportunity to compete in manufacturing the best parts based on their own specializations and capacity to innovate. The capacity for a professional market in services and support will also open up, along with training and other possibilities.

Sobering Factors

We need to realize that Kickstarter campaigns for individual projects will not save film photography. We cannot replicate the business practices of the industry before the end of the film era. Single projects will not solve anything — the collective output of the industry will become key.

Enforcement and licensing issues; the inevitable myriad of choices in how to license the software and other intellectual property. Obviously, the contribution to upstream solutions seems important and commercial use should be guaranteed. Should projects use BSD license? MIT? GPL? The Creative Commons?

Patents. Patents. Patents. This applies to the emulsions but also to chemistry. Currently, film photography is reliant on CPAC and Fuji C41/CN16 chemistry. Granted this should the platform we focus on but the death of Tetenal Europe proves a hard blow to this pursuit.

Having open standards for emulsions and chemistry might be a project worthwhile taking, though I’d argue the market is sensitive and displacing CPAC in the market in its current state is a terrible idea.

Film photography is a pastime enjoyed in excess of an economy. In the case of a global financial crisis, we are vulnerable to losing all innovations and potentially key suppliers could easily be wiped out across the board in this industry. Going the open source route, I’d argue, is key to the survival of this industry on one hand but essential for the preservation of the medium more generally.

Relevant Projects

- Debian/Ubuntu, the mainstream Linux operating system with largest hardware compatibilty.

- Imagemagick, open source command line based image manipulation program and library.

- Raspberry Pi, ARM based microcomputer.

- Arduino, open prototyping platform.

- Darktable, open source lightroom I guess.

- GIMP, the image manipulation program with the unfortunate name

- KINOGRAPH, open source moving image film scanning solution

- GNU General Public License GPL v2

- The Linux Foundation, the organisation responsible for linux kernel.

- The Creative Commons, open publishing licensing solution.

About the author: Emil Prakertia Raji is a photographer and musician based in Melbourne, Australia. Raji works at Halide Supply. You can find more of his work on his website and Instagram. This article was also published here.